Could The Fed Get Bitcoin Banned?

In This Episode

On this week’s episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour, Dan begins by dispelling several common rumors circulating about previous guest from Episode 153, Bill Browder. He also shares an incredible discovery from a new research project he’s working on.

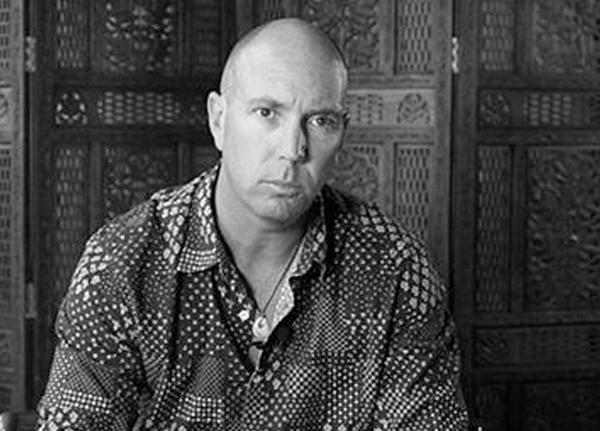

Then, Dan brings Chris Macintosh, onto the podcast for this week’s interview. Chris started his career at Lehman Brothers, Invesco Asset Management, JPMorgan Chase, and Robert Flemings. Since then, Chris has founded and built several multi-million-dollar businesses in the investment arena, including overseeing the deployment of over $30 million into venture capital opportunities.

Chris shares some of his macro thoughts on the long term effects of the Coronavirus with Dan. Dan and Chris discuss the measures being taken and the solutions being offered by the government. Plus, Chris shares some investment opportunities in unpopular sectors that are currently incredible values.

Then on this week’s mailbag, Dan answers some questions about Bitcoin and the Fed. Will the government try to ban cryptocurrency if it ever seriously competes with the dollar? Could a powerful future technology be capable of re-writing Bitcoin’s code?

Featured Guests

Chris Macintosh

Investor, Fund Manager, Advisor

Chris MacIntosh has founded and built several multi-million dollar businesses in the investment arena including overseeing the deployment of over $30m into Venture Capital opportunities and advising family offices internationally. Prior to this, Chris built a career at Invesco Asset Management, Lehman Brothers, JPMChase, & Robert Flemings. Chris now runs Glenorchy Capital, and publishes his investment research to subscribers of Insider, a subscription service providing customers with methods of positioning capital for unexpected events where, thanks to the mispricing of assets in certain markets, the target returns are multiples on capital invested, at relatively low risk. Chris frequently blogs at Capitalist Exploits and has built a following of more than 30,000 investors - from students, to fellow hedge fund managers, and even the odd central banker or two - and can be found on the likes of Zerohedge, RealVision, Seeking Alpha, Value Walk, Investing.com, Market Watch, Business Insider and Harvest... to name a few.

Episode Extras

NOTES & LINKS

- To follow Dan’s most recent work at Extreme Value, click here.

- To check out Chris’s research and insights, click here.

SHOW HIGHLIGHTS

1:39 – Dan opens the episode by dispelling several rumors about Bill Browder (guest from Episode 153) that have been spreading online due to a recent underground film. “The Magnitsky Act film is kind of a hatchet job backed by the Russian government.”

5:45 – Dan shares an incredible find from a new research project he’s working on… a book written nearly a century ago from long ago with some startling parallels to today. “This echoes a lot of the current era!”

14:30 – Dan reiterates why now is the time you want to own cash, precious metals, and Bitcoin…

19:14 – On today’s interview, Dan speaks with Chris Macintosh, who built his career at Lehman Brothers, Invesco Asset Management, and JPMorgan Chase. Since then, Chris has founded and built several multi-million-dollar businesses in the investment arena, including overseeing the deployment of over $30 million into venture capital opportunities.

24:59 – Chris explains how his background in investment banking led him to find a wide range of real estate opportunities.

31:24 – Chris shares some of his macro thoughts about the long term effects of Coronavirus with Dan. How much bigger will the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet get? What happens next?

38:42 – Can anything be done about the debt bubble? “Ultimately, I think it has to be a debt jubilee of some sort…”

42:12 – Don’t worry about getting in at the exact bottom with your investments. Chris says, “people who say they can pick the bottom are full of s!@#.”

47:10 – Chris shares some of his favorite ideas of what to do with your money right now. “Gold does okay but actually if you look over history, the best performing asset almost always is energy.”

53:40 – Chris shares why even though coal is down, it’s never going away. “You can cry all you want about killing the brown spotted owl, but at the end of the day, we’re not going to get rid of coal.”

1:05:45 – Dan answers questions from listeners in the mailbag… Would the U.S. Government ever outlaw Bitcoin? Is that even possible? Why would newly created money go back into the stock market? Could a powerful future technology re-write Bitcoin code?

Transcript

Announcer: Broadcasting from Baltimore, Maryland, and all around the world, you're listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music plays]

Tune in each Thursday on iTunes, Google Play, and everywhere you find podcasts for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive at InvestorHour.com. Here's your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value, published by Stansberry Research. Today we'll talk with investor Chris Macintosh. You may know him from the Capitalist Exploits website. He has tons of experience in money management, venture capital. He's built several multimillion-dollar businesses. He has a lot to say about all that and more. Stick around.

In the mailbag, the clouds part on Bill Browder, as some listeners chime in with positive comments. Plus listeners Brian G. and Will C. are worried the federal government is going to mess with their gold and their bitcoin. And, as always, my rant this week. I have a little bit to say about two totally different topics, including more follow-up on the Browder controversy that started when we interviewed him in episode 153. Then I'll tell you about my brand-new research project and how it'll affect your portfolio over the next five or 10 years. That and more right now on the Stansberry Investor Hour.

- Let's just talk for a few minutes about this Browder thing one more time. We interviewed Bill Browder in episode 153. He told an incredible story. I won't go through it again. Just listen to episode 153. It's incredible. Then we got lots of pushback in the mailbag last week from a bunch of people who said, "Oh, Browder's a fraud... He's a liar," etc.. And then after that, Browder had listened to our episode and he said, "Hey, I heard a lot of people said bad things about me. I've got some other evidence here that you may wish to look at." I didn't contact him. He heard about what we said and sent me a few things.

Now, one of those things was a presentation he did that basically – there's a whole bunch of things in this film called The Magnitsky Act that people think puts the lie to everything Bill Browder said, right? And he sent me a presentation that – basically it goes point by point. I'm not going to go through every single point. But I will tell you that some of the points that were made in the film that he says were false and defamatory – they said that Sergei Magnitsky, his lawyer who was killed in jail – the film said Magnitsky was not beaten up in custody. Browder's got tons of evidence that he was.

The film also said Magnitsky was not a lawyer – he was an accountant. Well, there's an article in the Moscow Times by Jamison Firestone, who was Magnitsky's boss at the law firm of Firestone Duncan [laughing]. So he worked for a law firm. We know that. And there's numerous court documents that say he represented the plaintiff here and there and everywhere just a bunch of times in Russian court. And he goes through all of those points and just kind of blows them away. In fact, this filmmaker, Andrei Nekrasov, he kind of changed his tune. He was like a radical but then around 2014 it looks like he's been working for the Russian government, saying favorable things about Vladimir Putin, whether they're true or not.

And there's one point in Jamison Firestone's article in the Moscow Times that I want to show you because it sounds funny in the movie, The Magnitsky Act. The filmmaker, Nekrasov, he's interviewing Magnitsky's mother, the mother of the guy who was murdered in jail by the Russians. And she says something that clearly means, "It's very difficult for me to accept the fact that Sergei was beaten before he died," meaning, "I'm his mother and it's just painful for me to have to accept this." But the filmmaker, Nekrasov, who is fluent in Russian and English – as Firestone says in his article, he disingenuously translates this to mean that it was difficult for her to accept that he was beaten – it was difficult for her to believe it. She believes it just – everybody believes it. Everybody knows he was beaten. But this guy – as soon as you see that he's twisting words around like this of the people he interviewed, you're like, "Oh jeez."

But, by all means, read Browder's book, Red Notice. See the film, The Magnitsky Act, and I'll see if we can't put some of these links up to some of the articles that Browder showed us that suggest that The Magnitsky Act film is kind of a hatchet job backed by the Russian government. OK? So that's that.

I want to move on to another topic, OK? I just started with a little research project which I think might turn into a big one. What I'm doing is: I just want to look for mostly anecdotal-type evidence that the period of 1929 through just say 1945 may bear some similarities to what we are going through, starting maybe with the 2008 financial crisis and ending – who knows? – another 10 years from now. Possibly ending in a war.

So what I'm doing is I'm just reading accounts of that time by various writers. And one of those accounts, which is really good so far – and I'm hardly into it – there's a writer named Frederick Lewis Allen. And he wrote two books. One is called Only Yesterday. That's about the 1920s. I think he published it in 1931. And the other one is called Since Yesterday, which covers the period from September 3, 1929 to September 3, 1939, and those two dates are instructive because September 3, 1929 is the peak of '29 market before it crashed. September 3, 1939 is the day Britain and France declared war on Germany. So it kind of bookends that period nicely.

And I'll just read you a few quotes. The parallels – when you go into a thing like this, what you've done – I've set myself up for confirmation bias, right? I've set myself up to possibly not be totally objective because I know what I'm looking for and I want to find that. But I have to tell you: already, just reading from a couple of books, from this and a couple of other books, the parallels jump off the pages. You don't have to look for them. They'll find you if you read anything about this period. So just a couple of quick quotes here from Frederick Lewis Allen, Since Yesterday. He says, "The holders and manipulators of securities are the chief beneficiaries of this last speculative phase of the Coolidge-Hoover prosperity," end quote. That sounds familiar, right?

Another quote. He says, quote, "You will hear that this is a new era, that the future of the blue-ribbon stocks is dazzling, that George F. Baker never sells anything, that you can't go far wrong if you are a bull on America," end quote. And who does that sound like? George F. Baker was a big banker and millionaire. He was the third-richest guy in the country when he died in 1931, after Ford and Rockefeller. He made his money after the Civil War in railroads and banks. And, by the '20s and '30s, early '30s, everybody was listening to him because he was this rich, famous investor. But it sounds just like Buffett, right? Buffett's favorite holding period is forever. He doesn't want to sell anything, right? And also: what does Buffett say? Well, "You shouldn't bet against America" is how Buffett puts it. "You can't go far wrong if you're a bull in America" is how Allen relates it here.

The idea that there's this big, famous investor touting America, this guy who never sells anything, right at what may be the top of the market of what may be the beginning of a very difficult period – it just screamed off the page at me.

And there are other smaller concerns. Well, they're big concerns, but just in the overall sweep of history. Like: at that time, there were concerns over, quote, "the displacement of men by machines, the turnover of men within industries, and the shifting of men from industry to industry, are making men less secure in their jobs, and especially are making it harder for men past the prime of life to get back into new jobs once they are displaced," end quote. That sounds a little familiar, doesn't it?

There was a lot of talk about tariffs back then. Of course the Smoot–Hawley Tariff by some writers gets some of the credit for causing the Great Depression. Alcohol prohibition was, according to Allen, the guy who wrote these two books I told you about, the hottest topic in America he says. The hottest topic in America. Well, what's one of the hotter topics of our time is the legalization of marijuana, and, by association, also drug prohibition. And also what's another huge hot topic? The so-called opioid crisis. So: similar topics.

And you could say, "Well, Dan, these are things that people are concerned about all the time, not just in these two periods." Sure. Of course. Admittedly. These are things Americans are concerned about. But they really came to the fore during this period of crisis, and during our period of crisis they are really becoming a lot louder and more important.

Here's another thing, a quote from Allen's book. Quote, "The collapse in investment values had undermined the credit system of the country at innumerable points, endangering loans and mortgages and corporate structures which only a few weeks previously had seemed as safe as bedrock," end quote. Do I even need to tell you the huge parallel of today? Lots of people going bankrupt. JC Penney, J. Crew, Lord & Taylor, just one after another is in bankruptcy these days. And we're also going to see some bankruptcies in the oil patch, right? Because oil went to negative $40 and is still a lot cheaper than it was before the start of this thing. Started the year at like $60-something. And I think we're still below $30. We're right around $30 here, maybe.

The Republican president Herbert Hoover, back in the day, quote, "Suffering from his inability to charm and cajole Washington correspondents was getting a bad press," end quote. Well, our president – he's not trying to charm anybody because he stands at the press conference and points straight at the reporter and says, "Fake new. You're fake news and you're fake news." So it's a little different but there is a similarity.

And now I want to get into something a little more substantial, OK? Now, in this book here by Frederick Lewis Allen called Since Yesterday, he points to six big changes that he says took place in the late 19th, early 20th century. And I think you'll find some parallels in recent history here. The first one: is the rapid progress of the Industrial Revolution, he says, "Transformed large numbers of people from economic agents into job holders made them increasingly dependent upon the successful working of an increasingly complex economy."

And the parallel is simply that globalization has made the entire global economy more susceptible to systemic risks, more susceptible to troubles in this part of the world causing troubles in that part of the world, right? A problem in the United States becomes a problem in Europe, and a problem in China becomes a problem in the United States, etc. You get it, right?

No. 2, huge increase in population. I'm not sure that's a huge deal for us today. No. 3, "Expansion of peoples of the Western world into vacant and less civilized parts of the earth, with the British empire setting the pattern of imperialism, the United States setting the pattern of domestic pioneering." So, I'm not sure really what the parallel is there. I mean, the world's a smaller place than ever, and you can live just about anywhere you want to.

No. 4: "The opening up and using up of the natural resources of the world – coal, oil, metals, etc. – at an unprecedented rate not indefinitely continuable." This echoes a lot of sentiment from the current era. Apparently when Americans get really prosperous, they start worrying about using up all the natural resources.

No. 5: "A rapid improvement in communication, which in effect made the world a much smaller place, the various parts of which were far more dependent on one another than before." And of course what has been our revolution in communication in the late 19th, early 20th century? The Internet has made the world a much smaller place than before. And I don't know if I would say the Internet makes us all more susceptible to systemic financial risks globally, but it certainly connects us and facilitates that connection. It's part of that connection.

No. 6: "New corporate and financial devices invented and put into practice." I mean, what was one of the primary factors in the 2008 crisis? Well, these things called CDOs, collateralized debt obligations, which were just sliced and diced bundles of mortgages that were rated AAA, and they weren't anything like AAA in the end. They were a lot poorer credit quality than anyone thought. So there's a lot of parallels I think. I think they jump off the page at you.

So what does this mean for us? Well, it may mean that we're headed into a period of great difficulty. Are we going to see another Great Depression? You probably won't hear me saying that. History rhymes... It doesn't repeat. So I think it's just necessary to look ahead. And you wind up wanting to hold three assets in a substantial greater quantity than you would otherwise I think. And those assets are cash, precious metals, and bitcoin.

I talked about bitcoin last week, and I've talked about cash and gold before, right? Cash takes care of you when the world is liquidating everything including gold and gold stocks. Cash is what you want to have. Cash is like oxygen – nobody ever thinks about it until they're running out of it, and you need to think about it before that. I'm currently around 25 or 30% in cash, depending on how I measure it. And to me that's a lot of cash. Twenty percent or more of your portfolio in cash is a lot. I think 50% or so is probably too much. So, plenty of gold, plenty of cash, and some bitcoin. In addition to buying great businesses. We're doing that. I'm recommending stocks in Extreme Value. We're finding long ideas. Don't get me wrong here. This is about asset allocation. It's about having a good portfolio, not selling everything and running for the hills. Because all this stuff – if it happens, if we do get a difficult five or 10 years, you'll want to be prepared for it. You can't predict it. You can only prepare.

And also one of the things that I can't help thinking about is William Strauss and Neil Howe's book, The Fourth Turning. So they've got this whole generational theory of history where we go through these periods that are one generation long. Maybe 18, 20, 25 years long. And they date the periods by events. And there are four of them every so often. They call them the turnings, the first turning and the second and the third and the fourth. And the fourth turning is the crisis period. The last fourth turning was 1929 to 1945. Big deal. I believe they say the fourth turning started this time around in 2008 and we're in the middle of it now. Does it end with a war the way the previous one did? I don't know.

But I know China's making a lot of noises and they've been making a lot of noises in the South China Sea. And there's this idea called Thucydides' Trap that suggests that when there's a world power and an up-and-coming possibly new world power, they're going to fight. Throughout history, that has happened. You've seen it again and again and they've always fought. There's a whole book about it that I have not read yet so I don't want to talk about. But I know about Thucydides' Trap because Thucydides was writing a couple thousand years ago.

So maybe we do end with some kind of a war. What would war look like in the 211st century when we've got cyber warfare and biological warfare? Who knows? It won't look like it did in World War II. We can be pretty assured of that. But who knows what it looks like? Who knows if it even happens? So I think you allocate differently, probably starting about now, and probably for the next five or 10 years. And when does this period, this fourth turning, if Strauss and Howe are correct – when does it end? Well, maybe somewhere around 2025, 2028, maybe later, maybe sooner. I don't know. I'm not saying I buy their theory wholeheartedly. But they make a pretty good case if you read the book.

So that's where I am on this. I'm just starting to look into this stuff. The parallels are leaping off the page. I think there are real hard and fast implications for where you put your money starting right now. That's all I have to say about that right now. Let's talk with Chris Macintosh.

[Music plays]

[Advertisement]

Today's guest is Chris Macintosh. Chris has founded and built several multimillion-dollar businesses in the investment arena, including overseeing the deployment of over $30 million into venture-capital opportunities, and advising family offices internationally. Prior to this, Chris built a career at Invesco Asset Management, Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan Chase, and Robert Flemings. Pretty cool stuff.

Chris Macintosh, welcome to the program, sir.

Chris Macintosh: Hey, it's great to be here, Dan.

Dan Ferris: And I assume you're talking to us live from Singapore?

Chris Macintosh: No. I'm live from New Zealand at the moment.

Dan Ferris: Oh, New Zealand. OK.

Chris Macintosh: I'm hunkered down in Mordor, you know?

Dan Ferris: Right.

Chris Macintosh: Along with everybody else that's hunkered down somewhere. It's one of these things where, at some point in time, wherever you were you pretty much had to stay. But, no, we keep a place here, and this is where I hang out a lot. So I'm in New Zealand at the moment. But, yeah, the business that I ran is based in Singapore. And that's where most of the business gets done. But as you are fully aware, I suspect, you can live anywhere you damn well please these days in our line of business. Most anywhere. Provided you have a half-decent Internet connection. So, yeah.

Dan Ferris: All right. Sounds good. So, Chris, we'll definitely talk about your investment style and what you think of what's going on these days of course. But I wonder if I could start by asking you: how old were you when your mind turned to finance and when you discovered finance and thought, "Wow, this would be a great way to spend a career"?

Chris Macintosh: I guess the realization came a little bit later. So I originally had this wonderful idea that I was going to become a lawyer. And I suspect that had more to do with the fact that I spent my teenage years reading John Grisham books. But then I went on to begin studying that, and in the undergrad part of that was economics. And on the economics side, I read some of the work – well, studied some of the stuff that we had. If you think of just Economics 101, it's pretty mundane, pretty boring. It's not the kind of stuff that gets most people interested. But I found it quite interesting.

And then I managed to get into the investment banks, in large part not because I was anything special but mostly because it was a boom. And this was just before – it was the '90s. So the dot-com boom was just getting going. And so really they were hiring any idiot and I was one of those idiots. And so I kind of fell into that world, so to speak, by luck. By the sheer virtue of the fact that there was a boom going on. I was interested in the space. I kind of wheedled my way in there. And that was kind of it. I mean, I carried on with the law side of things but it never really – I quite quickly realized that that wasn't going to be something that I was going to pursue. And then, yeah, I just got stuck into doing all sorts of weird and wonderful things in the investment banking world before leaving that to go and pursue my own thing, which has all been much more entrepreneurial in nature.

Yeah. I guess, to answer your question, probably like 20 – I was a 20-year-old... 19... 20.

Dan Ferris: So I'm curious: when you were at Lehman Brothers – I assume you weren't there in 2008.

Chris Macintosh: No. Lehman would've been '97, '98 I guess. Somewhere around there? It was well before a lot of that sort of fiasco. And then I was based over in London. I wasn't there particularly long. I'd actually just applied for and got a job in the equity derivatives desk at Lehman before the head of European equity derivatives – I know it's never come out in the news, but at the time he overdosed in the bathroom on cocaine I think it was.

And so that basically put a bit of a dampener on a whole lot of things, including all of the positions that he'd taken and the hires that he'd made and everything else like that for a three, four-month period prior. And I was one of those hires. And so my new job got put on hold until they could sort of figure things out. And I didn't want to hang around and wait for that to transpire. Because there was no indication as to what their time frame could be. I was being told it could be six months before things got ironed out. And so I ended up taking a job over at RF & Co., instead.

So it was well before the '08 crisis. And in fact I'd left the investment banking world by 2008 anyways. So I was fortunate enough to have been long gone before that all transpired.

Dan Ferris: So when would you say you became or started to become the macro investor that you are today?

Chris Macintosh: Kind of a journey, Dan. It wasn't sort of a one-off event, per se. I've done a whole bunch of stuff. In the investment banking side of things I've moved around and filled a number of roles. And then while I was doing that, I also got into real estate over in London. And I basically leased – I took long-term leases and then stuffed them full of short-term leases to arbitrage that difference. And I landed up doing that. And the numbers just kind of worked and so I kept doing it more and more until the point where I actually had this investment portfolio of real estate around London, which is pretty difficult to manage while I was also trying to work 70-hour work weeks in investment bank. But it had kind of given me a taste for that entrepreneurial side of things, and just looking at markets which were mispriced or had some arbitrage availability in them.

So I guess it was one of those things where you're looking at different – you're realizing that there's opportunity in pretty much any type of market or sector. And you can transfer those sorts of skills into many things. Whether you're sitting and you're looking and trying to arbitrage, I don't know, or just look for say deep value in any particular sector, it doesn't really matter if you're sitting at the desk or on the trading bank or whether you're in your hometown looking at the price of beans – it's the same thing. And so I did that. And then I left the U.K. because I didn't really want to have – I wanted to have a family. I met my gorgeous wife and we decided that we wanted to go and live somewhere else. We didn't quite know where that somewhere else was. But we knew that raising a family in a big city wasn't really what we were after.

So, long story short, we landed up in New Zealand. And so when I got here it was the same sorta thing: I looked around and said, "OK, what's valuable? Where is there opportunity?" And at the time that seemed to be real estate.

But, to answer your question on: when did it become a global macro thing? I'd always been looking at a lot of those macro type of environments. I guess probably – I grew up in South Africa where we had capital controls and a shitty currency. We still have a shitty currency. And so I looked at how people managed through that and the things that they did, for example. I'll give you a quick example. There's a gent that I met – I must've been about 16, and he had been trying to get – because you could take at the time I think it was about $20,000 out of the country, which is not a lot. And you had to prove that you were going on holiday and all this kind of nonsense.

Anyways, you couldn't get a lot of capital out of the country. And people tried – you know, they put Krugerrands in their bags and do that sorta stuff. But it wasn't particularly efficient methodology. And one of the things that he had done was he put barrels of oil on ships in Cape Town. And he had a corporation set up and he'd sell them off to Greece I think it was. Yeah, it was Greece. And he'd quote/unquote "sell" them to a corporate entity over there, and then that corporate entity would sell them to someone else. And basically all he was doing was just getting capital out of the country [laughs].

And I remember looking at all these things and just realizing that when you have these mispricing – look, if you got capital controls, you got mispricing. It's impossible to not have it, right? And you could say, "Well, that creates opportunity," which it does. So I guess going back, in hindsight, there was a lot of different events that made me look at the world in a different way and to assess it and evaluate it on a macro basis because it all – at the end of the day, I think macro matters massively. On a micro basis, in periods of low volatility or low geopolitical tensions and things of that nature, then macro doesn't really matter that much. When you've got a lot of stability, then you probably – it makes more sense to be micro. But, yeah, I've been drawn to trying to understand how the whole world functions and interacts for some time, and it's just been an evolution as opposed to a one-off sort of event I guess.

Dan Ferris: So, speaking of one-off events, we're living through an event that I sure hope is a one-off [laughs]. And it's one of those things where –

Chris Macintosh: Jesus Christ, yes.

Dan Ferris: Oh, I know. Like you say, we did live through a period of low volatility, and you could just sorta throw money at U.S. stocks for 10 years and it didn't really matter. And now all of a sudden it's like this guy Bill Fleckenstein who you've probably heard of says –

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. I know Bill.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. He says economics doesn't matter until it does matter, and when it does matter, that's all that matters. And I feel like macro depends on economic fundamentals. So we always want to talk to guys like you, and we probably should've wanted to do so like a year or two before, right? What are you doing now? How has the coronavirus and this very rapid change in the global economy – how has it changed the way you are looking at things?

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. Going into it, we had a view, both with our asset management firm and then the research side of things that run on the side of that, which is really just the research based on our asset management company – we had this view that we were moving quite swiftly towards what would ultimately be a stagflationary environment. If you go back and you think about kind of what preceded it, the Western world's built up this massive debt bubble. It's stunning proportions. And it's been over about a 50-year time frame. And then, look, it's deflating now. But it tried to do that in 2016 in the recession. It tried it in '08, in '01, in 1997, in '94, in '87, in '81, in '74. And if you look at just sovereign bond markets, you can see this long progression – each and every time we've had some of these – and it's gotten progressively worse. Like '74 was nothing. And '81, and even '87 was nothing like '08 in terms of the central bank reactions and consequent debt accumulation.

So kind of going into it, we had this hypothesis that we were going to be moving towards a stagflationary environment. That was built on the premise that we would have – in particular sectors we would have a supply deficit, and so that would bring about an inflation in those particular sectors. So if you go back and you think about how we've had inflation over the last couple of decades, economists and central banks I guess are – we fight the last war, right? It's like the general always fights the last war. And the last war with respect to inflation has been demand-led inflation. So it's been emerging market growth, for example.

Problem is that that emerging market growth that we've had also was coupled with a massive globalization, which was deflationary in aggregate. Because you're pooling and bringing into the global work environment a very low-wage – billions of low-wage earners who were prepared to work for the kind of money that people in the West are not – or wouldn't accept to work for. And so that had a very deflationary impact on many things. But in certain asset classes, we were going through getting to a period where there's going to be a supply crunch. And part of that is also from – the last commodity boom was sort of end of 2012, 2013. And so that buildup had been worked off.

And so we were kind of focused on that, coupled with the fact that monetary stimulus had already pretty much been done and dashed. There's nothing left really in that particular lemon. There's no more juice. And so we felt that – and it wasn't just a feeling. It was a matter of watching and looking at the language used by central bankers and so on and so forth – that we were going to move towards fiscal policies and other polices that would not be monetary in nature. With the belief that that would also change the inflation. Like I don't really try to think about inflation and deflation as these narrow concepts.

If I look and we see what has transpired – let's just take the GFC because everyone understands that pretty easily. After the GFC, everyone threw – central bankers threw monetary policy at that particular problem. And they channeled the fire hose of liquidity at the banks. Because it's kind of the easiest way for them – they figured was the easiest way for them to get a trickle-down effect: you put it into the banks, banks lend it to businesses, businesses lend it to people, boom, off you go.

That didn't quite work in the fashion I guess that they had wanted to, in that it never hit Main Street, right? And so what benefited from that was financial assets, was stocks and bonds and real estate. But it wasn't wage growth. It wasn't things that sort of matter to the everyday person. Which of course has also just built up a bit more of a wealth gap, which is – on a social pressure basis – creates more social upheaval and pressures.

So, going into it, that was kind of our premise. What I would suggest now is that quite a lot of that has been really I think exacerbated. And a big part of it I think has been brought forward. That debt buildup is just phenomenal. I wake up every morning and the numbers are changing so quickly that I can't even keep up with it, and I'm sitting looking at this shit all day long. You know?

Dan Ferris: Chris, are you talking about numbers like the Fed balance sheet for example is just growing?

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. Exactly. I mean, three weeks ago we were at $4.5 trillion. I think we're about $5.5, $6 now, already. And then they're going to put another $6 through over the next nine months. And we probably haven't even gotten started, Dan. And that's just in the U.S. So then we look across at other central banks around the world, and this is a coordinated effort I guess. Some are doing a little more than others, and so on and so forth. They've already tried a little bit of the monetary policy side of things. But I think there's a consensus now that that's not going to work. Europe and Japan tried it and it didn't work. So the Fed _____ seems to be at this point _____.

[Crosstalk]

Dan Ferris: Right.

Chris Macintosh: And I agree with that. I mean, I think that's true. And if you think about it, at the end of the day, if they lower another 50 basis points, does it mean that you say, "Hey, honey, let's go watch a movie... let's take the kids out for a dinner"? You don't. No one cares if rates go down. And so, again, that was inspired to push capital into the banking system and then the banking system to filter it through. But we're in different – we've never had this before. This is a demand and a supply shock all at once. And so you're not going to solve that with monetary. So they're going to throw fiscal at it.

And then ultimately I think there just has to be a debt jubilee of some sort of nature. I mean, we went into this crisis – or the U.S. went into this crisis with, what, a 31% structural deficit? And it aren't going to get better. We know that. If you think about the balance sheet side of things, it's exploding higher. And yet the revenue side, which is basically your tax receipts tied to GDP – well, we know what's happening to GDP right now, right?

Dan Ferris: [Laughs].

Chris Macintosh: And so if you and I looked at this like a business, it's pretty bloody frightening. If we were looking at governments as a business. So, yeah. I mean, I kind of feel like at the moment prices are just – we're in that sort of fog of uncertainty where you're in the car crash, and you're just trying to miss the trees. And I don't have any edge to play in that environment. People say, "Do I buy this booze, yeah? Or is it bottoming? Should I be long? Should I buy short?" And I'm like: I just think that's the wrong question to ask. Or maybe it's a question to ask with someone that has got better skills at that than I do. So I just look further out. I say, "OK, what are the consequences to what's happening? What happens when you come out of the car crash?" And I think what happens is you basically survey the carnage around.

And that's then when balance sheets begin to matter and solvency begins to matter. Because at the moment it's just – I mean, it's a liquidity-driven event. And in a liquidity-driven event, pretty much everything goes to one correlation. It doesn't matter. So you'll see gold getting sold. You'll see everything get sold because it gets called as collateral. If you've got to pay your bills, you've got to pay your bills. And if you and I are running a fund and we get redeemed, you sell what you have to sell. And typically you're going to sell what's also more liquid. Because it's easy to sell.

Dan Ferris: Of course guys like you attract assets though, right? You don't get redemptions [laughs].

Chris Macintosh: Yeah, 100%. So you want to look – for people trying to look for value, Jesus, there's a ton of it out there. But that doesn't mean that you are going to buy it today and it's going to work tomorrow. I think, again, you've got to say, "OK, what am I" – you've got to know what you're buying and why you're buying it. And I think that's the most important thing. Because otherwise you're going to get whipsawed. People will buy something and then they'll wake up the next morning and it's down 30%. Like, "Oh shit, I made the wrong decision." And I'll say, "Well, has the thesis changed?" Well, what did you buy? Why did you buy it? Was it cheap? Was it expensive? And if you can answer those questions then you can get a better sense in your own head as to having that ability to ride through that inevitable storm.

Because you're never going to low the bottom. You're not. And the people who say that they can pick it, well, they're either full of shit or maybe they are particularly good. But, I mean, I talk with _____ the top traders in the world, and these guys never pick the bottoms. They get close. And they manage and they league in and out of those positions and so on and so forth. But it's like probably, shit, 30% of the time that you're going to really actually nail that bottom. And that's if you're one of the best.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. If that [laughs].

Chris Macintosh: Hundred percent. I was just _____ _____ _____ – I mean, there's a good friend of mine and he's retired now. He's in his late 40s and he made a massive amount of money working as a prop trader years back. And he estimates that about 20% of the time he can get it kind of right. And honestly he's one of the sharpest, best traders I've ever met. And so if he can get it like 20% of the time – but then it's also all about position sizing right? He knows how to position size so that he doesn't get wiped out and league in and out of stuff.

And your average person's just not going to have that depth of skill and knowledge. And I don't. And I've been doing this for freaking most of my life. So I don't – it doesn't appeal to me to try and time that. So you want to look for: what are those asset classes that're really interesting? Where is the deep value? And then position size it so that you can not get whipsawed, so that you're not getting up at 2:00 in the morning and quickly checking your phone to see what the price is. If you're doing that then you're doing it completely wrong.

Dan Ferris: I think there's a lot of whipsawing going on these days, especially among retail investors. I think it's an insane environment. I call it untradable for a lot of things. Because I know a lot of people who listen to us on this podcast and read our stuff and everything – they're retail folks who, like you say, they don't have that depth of knowledge, and they think they're going to buy during a crisis. And then, like you say, then they're down 30% the next day. And it's too much. So let me ask you this, Chris: is there any place in particular – like on your website, Capitalist Exploits, there's a fair amount of discussion about various commodities and gold-mining stocks and silver and various other things here and there. How do you feel about those right now?

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. Gold... I'm not as – and I'm putting on a _____ for a bunch of your readers, listeners. But I'm not as bullish on gold as many are. Not that I'm not bullish. I just think, on a relative basis, gold is actually – well, firstly, retail owns quite a lot of gold. More interesting probably is silver, platinum. And other sectors – look, gold's kind of still a monetary asset. Precious metals, right? And so there's a very good reason to own them. If we're to be going into an inflationary environment – and that is our premise: I think that we're going to get NMT. For listeners, that's one monetary area which is just a fancy term for kind of debt monetization and allowing the market to tell the central bankers when they should or shouldn't monetize a certain amount of debt. So based on demand. So they reckon that's going to control things, both on the inflation or deflation side of things.

But really it just comes down to sort of Marxist ideology or a bunch of pointy shoes in shiny towers believing that they have the sufficient knowledge to know how the world works and to know which levers to push when and how. And if we look at history, that clearly indicates that that is a false premise. Nevertheless, I think we're going to go down that path. And I believe that it'll be inflationary. And if that's true, then if you want to be owning assets which are going to benefit on the inflationary side of things, gold does OK, but actually if you look over history, the best-performing asset almost always or actually always is energy. So there's a number of things in the energy complex that we're very interested in.

And, I mean, there's other things that are quite interesting in terms of agriculture as well. And we've got a bit of a nuanced view. A lot of people will look at that and say, "Oh, then you must be really bearish on the dollar," and I'm actually not – I'm very bullish on the dollar. So we've got a very – going into this, we doubled our dollar exposure, which benefited us really well, which was pure luck. I mean, shit, that was – there were a number of things why we felt the dollar was a good place to be. And those are still true.

But obviously we didn't know that a worldwide bat flu was going to arrive on our doorsteps and do what it's done. So in that respect it was lucky on that front. But – and this'll just I think exacerbate it. And we're seeing it now: there's a lot of collateral calls. We're going through a credit contraction. And with the global reserve currency being the dollar, that's always going to be bullish on the dollar. Just for the sheer fact that the dollar is the reserve currency. We don't know exactly what that figure is, but the estimates are around $13 trillion in dollar-denominated external debt. So that's a structural short that's out there.

And then if you think about: how does any debt get paid? Well, it gets paid with cash flows. And we know what's happening to cash flows globally. And so then collateral starts getting called and you start moving quite quickly into this type of environment – maybe the easiest sort of analogy I could come up with is the Asian '97 crisis. And that was set up with asset values that had just gotten out of whack. In this instance, it wasn't that asset values had gotten out of whack in terms of those external dollar-denominated debt. But cash flows are getting impacted this time. Right? And so you set off the same kind of spiral.

And, you know, one of the things – we've been watching EM currencies. And this is going back to 2017, 2018. And we started seeing a bunch of them starting to break. We were very short the South African rand. They've actually just – two weeks ago Moody's come out and downgraded them. So that's put a wind behind that trade. And –

Dan Ferris: You still in it?

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. South Africa's screwed. I mean, I wish it wasn't. I grew up there. But for a long time, EM managers have really just not understood what's going on there. South Africa in my mind is just like 30 years behind all the other disastrous countries surrounding it which have tried these Marxist policies. They just tried them 30 years earlier. And South Africa's just following the same – it's following literally exactly the same route. And, again, it's not about wishing – what I want to happen or what I – none of that matters. You've got to distance yourself from that when investing capital. But, anyways, you think about that... You say, "OK, what does South Africa produce?" You can synthetically short the rand just actually by being long the materials that it produces because those are also – there's supply constraints there.

You think about any Marxist-type country – does it produce more or less goods? That's a pretty answer, right? And then you go, "What does South Africa produce?" You know. And of course now we've got bat flu that's hit there and so they shut down 30% of their gold mines, just as an example. It's not just gold, it's all mines. So there's that kind of side of things to it. But ultimately I think we have – I don't know of it's going to happen, but smart investing is just a matter of probability and running those probabilities and then betting where there's an asymmetric opportunity and position sizing it such that you don't – if you're wrong, it's not going to kill you, and if you're right, you're going to make multiples on your money.

And, look, you're always going to look back and go, "Damn, I wish I had a bigger position in that." But that's the nature of it. You can't have your cake and eat it. So I think that there's a decent probability that the dollar really really runs more than anyone can even imagine at this point. But that will probably cause such a structural problem worldwide that it'll probably break it. I don't quite know what that looks like but I do know what I want to own at the same time as that, and it's things that're critical to society and humanity, which ironically are some of the cheapest asset classes we've ever seen. Like ever.

Dan Ferris: Like energy, for example.

Chris Macintosh: Like energy. I mean, if you think about coal, coal is like the devil, right, of all of them. Because we've had this whole climate hysteria, fossil fuel, _____ crowd, people chaining themselves to bridges, and all that kind of fun stuff. And then on the top of it we've obviously seen a massive divestment of investment in not only fossil fuels but especially in coal, whether it be sovereign wealth funds, whether it was BlackRock, whether it's just guys holding mutual funds. Everyone's gone, "No, no, me too, I'm out of this thing – we're not owning coal."

People forget that there's two types of coal – there's met and thermal. And at the end of the day, without met, you don't have iron ore. Without iron ore, you don't have steel. Without steel, we don't have any buildings. So you can cry all you want about killing the brown spotted owl, but, fuck, at the end of the day, we're not going to get rid of coal. And if you look back at history, whenever we've gone through transitions in terms of energy, we've actually never transitioned – transitioned is the wrong word. We've just added capacity, right? If you think about your cell phone, when we added bandwidth and storage capacity in our phones, all we did was just found other things to do with them, right? So you and I will now have a chat and we'll use video conferencing. Or we'll share videos of Asians falling off of bicycles or whatever the case is. So we find uses for that extra capacity.

And energy's no different. So when we transitioned from wood to coal, we actually continued to utilize the same amount of wood. It just meant that we used, on aggregate, way more coal. So coal made up a much bigger percentage of the overall energy composition. But our usage of wood didn't actually decline. In fact, we use more wood today as energy than we did when wood was the sole energy source that the world used. And the same is true of coal. When we went from coal to natty gas and oil and nuclear, we still continued to use coal to the same – actually there's even been growth in it. But on an aggregate basis, obviously natty and everything else took up a much, much bigger portion.

And so there's been this widespread narrative that we're going to basically give up all these fossil fuels and we're going to use wind and solar and unicorn farts and god knows what else, and that just flies in the face of both mathematics and science and history. And so then you look at how they're priced. Again, absolutely no capital has been going into these sectors. Like none. And so it's just stunning to me. But what it means is that you get a severe mispricing of assets. Again, if I think about coal, today we have, around the world – and most people just don't think about this because they read the headlines. But there's a massive buildout in coal-fired power stations. In South Africa, which we were just talking about, they got about 79 plants. They're building 24 more plants.

What else? We got India. India's got about 590, 589 I think it is. They're building 446 more. The Philippines, South Korea, Japan – Japan's got about 90. They're building another 45. China's got like nearly 2,500, 2,363 I think it is. And they're building another 1,100 and something. There's just massive buildout of – _____ _____ _____, "Well, where's the coal going to come from and who's going to finance it?" And then you look at the whole coal space and you've got these companies, Dan, which have – they've been through restructurings often. They've got no debt. Their dividend yields are like 17, 20, 15. And they're trading at like half book. And you just look at this – so, again, you can buy these things... tomorrow they might be down 30%. I don't know. But what I do know is that the probability is that they won't go away. Right?

And they can take pretty much any hit because they don't have any debt or they have really low levels of debt. I mean, there's plenty of them out there. People can go and look. There's Arch Coal. There's Stanmore. Stanmore's got no debt. Arch Coal's got low debt. Anyway. So when you think about that and then you think about the trillions of dollars that're being thrown at this, which ultimately have to get monetized – and I think they have to get monetized because when you have the vast majority of a population – and this is globally, not just talking about the U.S. and the Western world – that are debtors, you're going to sacrifice the creditors to the debtors. Because it's not politically feasible to do it the other way around.

So if or when that transpires, then you want to be owning stuff, for one thing, and you want to be in a position where you're not taking balance-sheet risk. I mean, I think we come out of this car crash and that's when balance sheets matter. Solvency matters. And it'll probably be at the corporate level first. And then it's going to move towards the government level, where at some point government solvency matters. Especially when they start monetizing debt. So that's kind of how my playbook looks like at the moment, and how we're positioning for it.

And I don't pretend to know how this is going to look. I do know that we're going to have a massive hit to global GDP. And I think it's a long, grinding one. I don't think it's short and sharp. And so I think there's a huge opportunity in terms of a transfer of wealth that's going to take place. That fire hose of liquidity – that was basically centered at financial assets. And they're going to have to move that fire hose over to Main Street. And that's going to completely alter how capital gets allocated. Your average person in the street doesn't give a shit about whether the Dow's up or down, right?

Like even if you've got a relatively big 401(k), as you guys over in the States have – let's just say – use easy numbers. Let's say you earn, I don't know, $100,000 a year, and you've got $1 million in a 401(k) – I know most people wouldn't have that, but let's just use that as numbers. If the Dow's up or down, yeah, you'll be, "OK, that's cool." However, if you lost your job, that becomes much, much more prevalent on a _____ basis. And that ratio is probably more close to $100,000 income and maybe $250,000 in your 401(k) or $500,000. And so your point of pain is in cash flows, right? Much more importantly. Because you can't live off of the – even if you have your half-a-million dollars in your 401(k) and it goes up by, I don't know, 20%, does that replace your lost income for a year? Nope.

And then you get into the position where, oh, if that's the case you're going to start liquidating in order to pay your bills. Well, what if everybody's doing that? Well then it's not really possible for that 401(k) to go up because everybody's on the sell side, not on the buy side. So, again, targeting financial assets is a waste of time, and I don't think the central banks – I think they've realized that. So they're going to target Main Street, and it's going to be fiscal spending, and it's going to be direct money injections into the patient. And that's going to have a vastly, vastly different impact on inflation and deflation and asset and asset classes. And that's where we're focused. And I'm very excited about it. Excitement's not a good feeling for an investor to have because I don't think you should ever be –

Dan Ferris: Right [laughs].

Chris Macintosh: Don't buy your own shit.

Dan Ferris: Right. Don't buy your own BS.

[Crosstalk]

Chris Macintosh: _____ _____ _____ _____. Yeah. So you've always got to try and put that in context and make sure that you're not seeing things that aren't there because you want them to be there – I guess is the way I'd think about it.

Dan Ferris: Perfect. We've actually come to the end of our time. But I don't want to ask you any more questions because you've painted such a clear picture here that I want that to be like the last thing the listener has in his head [laughs] at the end of this. You know, it's funny because a lot of the macro guys have been talking about strong dollar. And now of course the discussion about from monetary stimulus to fiscal stimulus is gaining a lot of traction. A lot of it. It's nice to talk with somebody who kind of has figured all this out and knows what to buy and where to look. And I hope our listeners kind of took notes and are getting some good ideas from that right now.

But, Chris, you'll have to come back. Especially with you and considering what's going on right now, you'll have to come back in, I don't know, whatever it is, six or 12 months, or some period of time that makes sense, and sorta tell us where you are then. Because god only knows where the world will be, where the global economy will be. I'm just curious about a couple of things that you've said: the dollar and energy and coal and things. Maybe we'll just make a tentative date I hope [laughs] to get back together maybe in six or nine or 12 months or something.

Chris Macintosh: Yeah. I'd love to.

Dan Ferris: OK.

Chris Macintosh: I would love to. My wife always bitches and moans: I can talk about this stuff all day long.

Dan Ferris: Well, good. We'll talk to you again, hopefully sooner rather than later.

Chris Macintosh: I will look forward to it. Dan, thanks so much. And take care.

Dan Ferris: All right. You take care, Chris. Thanks.

All right. That was quite a good talk. We heard a lot of ideas from somebody who obviously carries a broad sort of detailed picture of where the world is and what's happening and can drill down into parts of it sort of at a moment's notice. It's really cool, and I hope you heard the similarities with other macro guests, Raoul Pal and Kevin Muir and Cullen Roche and Mark Dow and things. Most of them have maintained strong dollar, rising gold, but maybe gold's not the greatest thing. Good but not great. A lot of themes here come up with people who are capable of seeing the world this way. Really interesting stuff. I hope you enjoyed that. All right. Let's move on.

[Music plays]

In the mailbag each week, you and I have an honest conversation about investing, or whatever else is on your mind. Just send your questions, comments, and politely worded criticisms please to [email protected]. I read every e-mail you send me, every word, every word, and I respond to as many as I can.

First off this week is Mike K. Mike K just wanted to say, "Hey, just got around to listening to the Investor Hour with Bethany McLean. Very upbeat. A real person. Definitely worth hearing her speak. Refreshing," Mike K says. And I just wanted to note, we interviewed Bethany in episode 148, and it was a good interview. Go listen to it.

Next up is Brian G. Brian G says, "Hi, Dan. This is not Russian spam but I'm hopeful you'll read it anyhow." I don't read the Russian spam, Brian. I don't read Russian spam anymore. I used to. Brian continues, "With respect to bitcoin, here's the reason I have not invested in it. The Federal Reserve will have to deal with this as a competing currency, and when this becomes an issue, the U.S. government will outlaw all electronic currencies except anything issued by the Federal Reserve. Seems to me this could be quite detrimental to one's alternative currency investment. It's not as though this type of thing hasn't happened before. See 1933, United States, gold. I'm interested in hearing your comments on this issue."

- Brian, I hear you. If bitcoin really gets hold, the Fed won't like it. The problem is: they won't be able to do anything about it. What are they going to do? This thing is designed – it's heavily encrypted. It's designed to be completely outside of the financial system. And, frankly, so is gold. What're they going to do? Go to everybody's house and steal their gold? I don't see it happening. I'm not worried about this at all. In fact, I think it's brilliantly designed for that expressly in mind.

- So next comes Brett R. And Brett R says, "Dear Dan, really been enjoying your episodes lately. Bill" – Bill Browder – "has a riveting story, all details aside. I tend to side with an American over the Russian government on who to believe but I'm sure neither side is saintly, per se. I commend you on having a strong spine when dealing with your critics. I'm not sure I would be able to handle it as well as you. In response to them, it seems clear to me that you're not into thoroughly researching a guest prior to having them on. There have been times when I'd wished you'd press harder with some guest." Etc., etc., Brett R.

OK, listen, I hear you, Brett. And I said, "Look, I should've known about that Magnitsky Act film before we interviewed Bill Browder." But I don't think it turned out badly that I didn't. So you're right: if I like a guy, I like his story, I'm going to go, "Hey, ready, fire, aim." And I'm going to get on him and talk to him as soon as I can, and then if things come up, I'll handle it. And, look, I hope by now everybody knows that if I interview somebody and something is completely misrepresented, yours truly is going to get on at the first opportunity and say, "You know something, guys? I got this wrong." I've done it before and I promise you I'll do it again.

In fact, folks, that is one of the reasons I agreed to take over the podcast from Porter and Buck in the first place: because I hate the way financial news media always acts like whatever's happening today, they saw it all along, and they never go back and revisit their mistakes. We aren't going to do that around here. We're going to be real with you. But thank you, Brett R, you gave me an opportunity to get real [laughs].

Next is Matthew M. Matthew M says, "Big fan of the show. I've learned a lot from you and appreciate you. I have a question on your statement – and I'm paraphrasing – that the Fed doing QE" – quantitative easing – "has shown to not create inflation because it's a zero-sum game in that they buy the Treasury bond with digital money they create but take the Treasury bond out of circulation." Then he has several questions here. I'm going to answer them one at a time.

First question: "Did we not see money creation at the commercial level due to artificially low interest rates that caused rising prices in the stock market and not so much in consumer goods CPI?" Answer, Matthew, is yeah, we do see money creation. Banks lend money into existence, if that's what you're talking about. So the answer is yes.

Next question by Matthew M. "My question is: why wouldn't artificially lowered interest rates cause more money creation at the commercial level?" Well, it does, and you're right. "Also: why would it be at all likely that the money created off of lower interest rates this time would go into the stock market or U.S. assets again and cause a strong dollar? I don't see this strong dollar. Who wants to invest in a company with a lot of debt after COVID?"

Now I assume, Matthew, that you're making an analogy between the federal government as a company – you're saying it's like a company. I don't think so. And your question is a good one though: why would the newly created money go into the stock market or U.S. assets again and cause a strong dollar? It's still 60% of all the foreign exchange in the world. And it probably settles 80% of all the transactions in the world. It's very, very, very hard to sell anything without buying dollars. Very hard. So, this is not something that I think will happen forever either. Remember, the thesis here is: the dollar becomes super-duper strong because we get another liquidation event similar to what we saw in March of this year, and because of that, that demand for dollars, it gets so strong that it breaks itself because it's too strong. When a currency gets too strong, it has a very depressive effect, and people are like, "Screw this. We're going to print money." Right? That's the idea.

And finally he says, "Do you think investors will accept high debt levels and blow this bubble up again in stocks or do you see it more likely that consumer prices get bid up and we get very high inflation, higher prices?" I don't know, Matthew. I don't know how it exactly plays out. But you're pointing in a generally good direction. The federal government borrows and borrows and borrows, meaning that the reserve is printing and printing and printing and buying up the securities, the debt securities that constitutes federal government borrowing. And eventually this pisses investors off and they buy gold and sell dollars and it turns against them. That's what's happened historically. Lots of great questions. I'm glad. You should be asking them.

Next is John A. He says, "Thank you for this episode with Bill Browder. It was so riveting I shared it with others, some of whom were personally affected by the horrendous ban of international adoptions from Russia by Putin. I could write 10 more pages about this but I will spare you. Stay well. Keep up the great work." Thank you, John, for the comment.

OK, now, Will, C is wondering about bitcoin. I won't read the whole thing but he says, "For example, quantum computers seem far-fetched but not impossible and could break current cryptography. There's also the hypothetical of a single actor gaining majority control of the network on which bitcoin is traded. Twenty-one million bitcoins are only fixed because the network agrees this is the limit. A powerful actor could rewrite this code, and with enough network control, change would propagate through the network. Probably impossible but maybe no different than pulling gold out of the ocean. Keep up the great work, boss. Thank you, Will C."

Thank you, Will. Yeah. So I mentioned a technology like something pulling gold out of the ocean as possibly creating a lot of new gold, right? That could affect the value of gold. But overall, I think even that would not completely ruin gold as a store of value. I think it's unlikely that we get that event that you described in bitcoin. But, you know what? There's a reason why I don't say put all your money in bitcoin, why I say buy good businesses in the stock market, hold lots of cash, hold gold, and hold some bitcoin too. That's why we diversify: because there are risks in every asset. And you're right to point them out.

- Matt O wants to criticize me because he says, "I'm surprised by the incredulity you expressed at someone calling a plumber to their house during the COVID-19 pandemic." All I'll say, Matt, is you're right. When I was saying that – that was a while ago – I was a lot more concerned than I am now. And you're right to call me out on it.

RR from Texas wrote a big long e-mail that amounts to a criticism of – he's talking about how in New York – this ventilator situation in New York, which is a highly regulated market and doesn't let people build new hospitals or surgery centers unless they get this certificate that says they're allowed to do it. In other words, the government is limiting the supply of these things. Whereas in his state of Texas, with 48% more population, they didn't need ventilators. New York said it needed ventilators, cost millions of dollars to get them there, and Texas has a free market in hospitals and no problem.

RR, your point is well taken. And I totally agree with you. It's ridiculous. Why would you willingly limit the amount of health care that can be provided by limiting – if a doctor wants to invest in a new surgery center or doctors get together, investors want to build a hospital, why limit them? Why prevent them from doing so? Why limit the supply? My view on this is that: you know how it goes, man. Regulations are generally put in place and supported by the large incumbents in any industry, right? The big banks love banking regulations because it makes banking more expensive. It makes it harder for up-and-coming competition. And you can see that in lots of industries. We've talked about this before. But now we get an example in the health care industry in New York. Really good insight there, RR. Thank you.

Well, that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. Do me a favor: subscribe to the show on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, help us grow the show with a rate and a review. You can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Our handle is @InvestorHour. Have a guest you'd like me to interview? Drop us a note at [email protected]. Till next week, I'm Dan Ferris. Thanks for listening.

[Music plays]

Announcer: Thank you for listening to this episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to InvestorHour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail: [email protected].

This broadcast is for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

[End of Audio]

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.