The Best Shape of Your Life At Any Age

In This Episode

Every year, the top resolution for millions of Americans is to lose weight and get in better shape.

But the numbers show this is far easier said than done.

So this week, instead of focusing on your wealth, we’re taking a look at your health as Dan brings fitness guru and internet sensation, P.D. Mangan, onto the show.

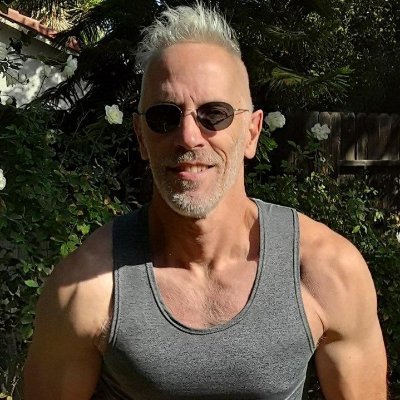

P.D. shares the story of how at age 50, he was frail, feeling terrible, and in general poor health. But today at age 65, he’s in better shape than most 20-year olds.

P.D. shares the shockingly simple way he did it – without the help of dozens of supplements or steroids – and without spending endless hours in the gym. P.D. is unique in that his advice typically goes against what many traditional health experts have been saying for decades.

Today, he helps teach folks of all ages how to eat right, get stronger, live longer and win with science-based health and fitness.

Listen to his discussion with Dan and more on this week’s episode.

Interested in more from Stansberry Research? Check out the American Consequences podcast here: https://podfollow.com/americanconsequences

Featured Guests

P.D. Mangan

Author and Health & Fitness Maximalist

Author and Health & Fitness Maximalist

Episode Extras

2:42 – Dan opens this week’s rant revisiting his Top 10 Surprises for 2021 from last week’s episode. Some may ask, if they’re not predictions, why do it? “Because they’re not priced in. Nobody is expecting these things… If they happen, they’re really going to hurt.”

9:10 – There’s signs of excess everywhere in the markets and Dan is reminded of the Dotcom bubble. “It’s when everyone knows and thinks it’s a bubble that you have to start getting worried… Anytime everyone agrees on something, just take a second look at it…”

14:11 – The quote of the week comes from Martin Niemöller who famously said, “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionist, and I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak for me…”

15:48 – On this week’s interview, Dan invites P.D. Mangan onto the show for something a little different. This week, we’re focusing on your health, not your wealth. P.D. shares details of his fitness journey including how to eat right, get stronger, live longer and win with science-based health and fitness.

19:35 – Dan questions P.D. about how he got in incredible shape at age 65… “You did things very differently than what many mainstream health and fitness and diets sources tell us, right?”

23:20 – P.D. explains how processed foods tend to be much more profitable than whole foods… and how that incentive impacts how we shop and what we eat.

27:41 – How has our diet changed over thousands of years? “People are just eating all the time now. It’s almost seen as heroic if you can go 2 hours without eating something… If human beings needed to eat that often, we would have never survived.”

30:30 – P.D. walks Dan through what his new diet looks like in a typical day. What he eats is just as important as when he eats…

34:05 – P.D. explains why aerobic exercise alone just doesn’t cut it… “What happens to human beings as they age, is that they lose muscle… By the age of 30, loss of muscle can be noticeable, and it accelerates with each passing decade…”

36:45 – Dan is floored when P.D. reveals his workout schedule, “You only work out an hour a week?! And you look like that?”

44:22 – “Exercise makes you hungry… and processed foods makes it really easy to down the calories. So burning calories to lose body fat just doesn’t work. You have to get your diet in order.”

48:05 – P.D. leaves the listeners with one final thought before he leaves, “Eat real whole foods, not ultra-processed foods and do resistance training and you’ll be healthier than you could ever be doing anything else…”

51:00 – On the mailbag this week, Dan answers whatever is on your mind. One listener presents Dan with an interesting thought experiment on Tesla’s stock. Another listener adds their own surprise for 2021 to add to Dan’s list. And another listener asks Dan’s opinion on the best books to read to learn more about managing risk in your portfolio. Dan answers these questions and more on this week’s episode.

Transcript

Announcer: Broadcasting from the Investor Hour studios and all around the world, you're listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music plays]

Tune in each Thursday on iTunes, Google Play, and everywhere you find podcasts for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive at investorhour.com. Here's your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value, published by Stansberry Research. Before we get into today's episode, don't forget... Trish Regan is now a part of the Stansberry family. Check out her podcast, American Consequences With Trish Regan. The link will be in the description of this episode.

Today we will talk with P. D. Mangan. He's here to talk about your health, not your wealth. What good is wealth without health, after all? P. D. will tell us how he got into the best shape of his life and how you can do the same. It's real simple. I can't wait to talk with him. This week in the mailbag, we had lots of great e-mails about all kinds of topics, too many to name. But once again, you actually came close to sending me more and longer e-mails than I could read but I did manage to get in every single word of every e-mail you sent me. But you're almost there. Keep it up. Send lots of e-mails.

In my opening rant this week, man, it didn't take long for me to need to update my 10 surprises. But I will update one of them. And we'll just talk about them again in general to clarify, based on some e-mails that I got this week. All that and more right now on the Stansberry Investor Hour.

- Let's just talk about these 10 surprises. I got some e-mails that showed me that I need to clarify what we're doing here one more time. The 10 surprises for 2021 are not predictions. I am not predicting that these things will happen. I am not predicting it. I am frankly acknowledging that they are unlikely. Most of them I feel are pretty unlikely. And if you just take my No. 1 surprise, which is the first one I read – it's also, for me, the biggest – it would be the biggest surprise if it happened: would be that the S&P 500 drops more than 20% in a single trading session. And we talked about why that is. You can listen to the surprises episode last week if you want to find out more.

So these are things – if they're not predictions, why do it, right? That's what you're wondering maybe next. Well, because they're not priced in. Nobody's expecting these things. If they happen, they're really going to hurt. Most of them, if they happen, they're really going to hurt. So they are basically risks that, in my opinion, are not priced into the market right now. I mean, nobody's pricing in the 20%-plus daily drop, right? Nobody's pricing that in. And even my No. 2 surprise was that it would be a big surprise if the S&P 500 did the same thing it did last year, which is make a new all-time high and then breach the March 2020 low for a new lower low and higher high.

Let me just reiterate one final time this week: I'm not predicting these things are going to happen. I'm saying they are largely unlikely things, and therefore investors are not prepared for them, right? So it pays to think about them because it's likely you're not prepared for them.

And I said we needed to update. What do we need to update? Well, bitcoin, right? And I frankly acknowledged in my bitcoin surprise: what would surprise anyone now, right? And we decided it was just a wider range of outcomes than anyone could father, right? So if bitcoin hit maybe $500,000 or some crazy number this year, I think that would surprise the hell out of everyone including the most bullish bull. And if it fell 90% – it peaked at almost $42,000. So if it went back down let's just say near that low that it hit back in – what was it? – 2017? I think it was around $3,000 or so. If it got back there, I think that would surprise everybody. So, in the past week, what happened? Well, we were up to almost $42,000 and then it was down to $30,100. That's a pretty substantial move. But it's not even 30%.

See, maybe it upsets some of the bulls, right? But this is not what I'm talking about. This is not the surprise. It could develop into it. But it's not it. So as far as I'm concerned – what have I always said about bitcoin? I've said I think it's a burgeoning store of value that has a great long-term outlook but it trades like a mining stock. It's highly volatile. Or a biotech stock. Or any other kind of super-volatile thing. Commodity futures, whatever. It's really volatile. And I think you should expect it to continue that way. And I would frankly be surprised if you did not see at least a 50% drawdown from a new high.

So if we're correct here and we're in the mid-30s as I speak to you, after having topped out almost $42,000 – if we went down to like $20,000 or $21,000, something like that, that would not surprise me. And it wouldn't surprise me too if we got this correction down to $30,000, then we doubled, $60,000, and then went back to $30,000. You know what I'm saying? That's the kind of action you should expect from bitcoin. Even though long-term I think it is probably going much higher and is worth at least a small position.

- Other than that, I'm just looking around and I'm seeing lots of signs of excess. They're everywhere. And one of the most recent ones I saw – I get this thing called The Daily Shot, which is a whole bunch of charts and data every single day in your e-mail box. Pretty cool. And one of the things they published recently this week was the S&P 500 versus the Goldman Sachs retail favorites index – the favorite stocks of retail investors. And you can kinda guess what they are. We actually mentioned them in the surprises. We mentioned Tesla and we mentioned the FAANG stocks, right? Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google. Those. Those are the retail favorites. And I'm sure they probably have others in their index.

Well, since last August, the S&P 500's up about 20% and the retail favorites index is up 70%. And if you look at the charts, it's gone ballistic. It's going straight up just over the past few weeks. So people are more in love with their favorite stocks – they've fallen more deeply in love than ever before, OK? Which to me – there are all these different sentiment indicators: the AAII and Investors Intelligence and all these things. I've learned to kinda discount them because, unless they're all at extremes, really extremes, really high or really low extremes at the very same moment, it's a mixed bag on their predictive capability, really is.

But I saw another thing on Twitter which I thought was really interesting. And it was this guy – his name is Corry Wang, and you can find him on Twitter: C-O-R-R-Y Wang, W-A-N-G. And he's got this little thread. He said he spent his winter holiday reading hundreds of pages of equity research from the 1999 to 2000 era, and apparently he works for or did work for Bernstein Research. He used to work for them so he's got all this stuff. And he read hundreds of pages of it on the last gigantic equity bubble that we had. And he's got some good lessons for us.

The first lesson was: everybody knew it was a bubble. People used to say, "If everybody says it's a bubble then it's not a bubble." And that just isn't true because people were talking about this thing, as he points out, being like tulip mania in 1998, and the market soared after that, right? So everybody was talking bubble talk a year or two before the bubble peaked, right? Everybody can know it's a bubble – I think in fact my point would be a little different. I would say it's when everybody knows and thinks it's a bubble that you really have to start getting worried, right? Or everybody's constantly talking about a bubble. Everybody agrees. In other words, anytime everybody agrees on something, just take a second look at it.

And his second lesson was that calling bubbles is easy but making money is hard. I wrote about this a couple years ago in Extreme Value and I used the example of Apple. If you tried to trade Apple around the top of the dot-com bubble, you probably got whipsawed and didn't make any money. Long or short. It was just too hard because you were just up 100%, down 50, up 80, down 40, like that. And it happened so quickly. Anybody would've gotten stopped out. And even to short, you would've had to – the only thing that I could see someone doing is if you had bought some way-out-of-the-money put options out maybe six, nine, 12 months, something like that, and held through all that initial froth and just decided, "This position's going to go to zero or it's going to be way in the money at some point." But you're ready for it to go to zero if it doesn't work out. I could see that maybe working, and I personally have some very small positions with that in mind. But trading the actual equities, it just looks impossible to me.

His third lesson here is that nobody knew the bubble popped until months after it did. He said, "Nobody noticed in March 2000 when it finally popped." He says, "The Bernstein equity strategist who bet his career on it didn't catch on until June." Another lesson was that it was really a large-cap growth bubble – it wasn't just a tech bubble. And lots of stocks like – not only did AOL and Cisco and Dell Computer perform lousy for the next ten years, whatever, but also Coke and Pfizer and General Electric and Johnson & Johnson and other big-cap growth-year names too.

And then the other thing was that the fundamentals – one of his other lessons – I won't read them all. The fundamentals followed the price. The bubble peaked in the first quarter of 2000 but the fundamentals did not decelerate until the fourth quarter. So he says it's reflexivity at work. And George Soros has this idea about reflexivity which, if you read about reflexivity in his book, The Alchemy of Finance, or I think he also wrote about it in Soros on Soros, it's just circular. It goes around and around and around. It's the craziest thing. But the idea here is... lower stock prices translated into less capital spending, which translated into less revenue growth, which translated into lower stock prices. In other words, the market action – the price action actually influenced the fundamentals. That's one of the basic ideas in reflexivity. And created a vicious cycle.

And his takeaway is: be humble. It's easy to call a bubble. Anybody can do that. But timing it is the hard part. And I would say timing it is like – it's next to impossible. You have to be willing – in my opinion, if you want to do it at all – it's probably a fool's errand – you have to be willing to do it with money that you can afford to light on fire is the only way for me to put it. But we're there. We're in a bubble. And you need to be careful and you need to be prepared.

So let me do my quote of the week now and then we'll have today's guest, P. D. Mangan, who is – I can't wait for you to hear from this guy. He's got great simple ideas about diet and exercise. Quote of the week comes from Martin Niemöller. And the reason I chose this was because, as you'll hear in the mailbag today, one of our listeners wrote in and gave us his version of this quote, which most of you will recognize. It's very famous. It's permanently on the wall at the Holocaust Memorial in Washington D.C., and it's a very famous quote. But I think the time is right for it. And the time is really right for the listener version that I will read later in the program.

But Martin Niemöller was a priest and he welcomed Adolf Hitler's Third Reich with open arms but he was quickly disillusioned. He found out his phone was bugged and this little group of priests that he organized was being surveilled by the Gestapo, the German state secret police. And so he knew that he was in a totalitarian dictatorship. It was nothing like what they claimed in the beginning. And he opposed it. And he said, very famously – and you can read it on the wall at the Holocaust Museum in Washington. He said this: "First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out – because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out – because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out – because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me."

If you disagree that that's not a perfect quote for this moment in our history, write into me and explain yourself how that could be true. And I'll just say frankly: all this business at the capital – if you use the words insurrection or coup, you're demonstrating that you have no understanding of what took place. It was a bunch of thugs. It was a bunch of jackasses breaking the law, breaking and entering and acting like idiots. It was more like frat boys gone wild or something. They drank too much and took to the streets. And maybe they were fired up by what Trump said or not. I don't know. But to call it an insurrection or a coup – come on. That ain't what a coup looks like. I promise. If you have ever lived in a place where a real coup took place, write in, [email protected], and school us. And you tell me. Maybe I'm wrong. You tell me. I don't think that's what a coup looks like at all. So if you know, if you have experienced one firsthand and been there when it was happening, you write in and you tell me what it looked like.

All right. Let's talk with P. D. Mangan. Let's do it right now.

[Music plays]

Today's interview will be a little bit different. We won't be talking about your wealth – we'll be talking about your health. And today's guest is P. D. Mangan. P. D. Mangan can teach you how to eat right, get strong, live long, and win with science-based health and fitness. His website is roguehealthandfitness.com. P. D., welcome to the program.

Dan Ferris: Thanks, Dan. Great to be here. Thanks for inviting me.

- D. Mangan: You bet.

Dan Ferris: P. D., I found your personal story very compelling on your website. And especially I found the photographs very compelling. There's a photograph of you in your 50s where you look kind of thin and you said you weren't feeling that great. And then there's this photograph of you recently, and you are the picture of masculine health. You're all muscular and you look great. So tell us, if you will, what happened in between there?

- D. Mangan: Yeah, right. Well, putting it succinctly, yes, I was in ill health at the time of that photo in my early 50s and I had been in ill health for a few years. Basically from following standard advice that I thought was going to keep me healthy and fit. I had been a long-distance runner and I had become a vegan. And I did OK for a while but then ended up with chronic fatigue. So I went to a number of doctors and – quite a few. I must've seen a dozen. And nobody could seem to help me very much. And so this went on for several years. And at some point I decided that I was going to have to take matters in my own hands if I ever wanted to be healthy again. So I started researching and looking around. So you saw that photo of me when I was in my early 50s.

Anyway, one thing I did was stopped being a vegan and started eating a real whole-foods diet, largely centered on meat and other animal foods. And I started lifting weights. So the lifting weights part – I mean, I started getting better when I changed my diet. And then when I started lifting weights, that was very tough but I kept at it, and it wasn't long before I realized I needed bigger weights or heavier weights. So I joined a gym and proceeded to put on a lot of muscle. And at some point in my journey, if you want to call it that, I thought – I'd been doing a lot of research and I thought, "Well, if I ever figure this out and get better I'm going to have to write about it." So after I got better, I remembered that. "Well, I guess I better write about it." So I wrote my first book called Smash Chronic Fatigue.

And then after that I just decided to keep going. I thought, "Well, what's the next step? I guess keep writing." So I've been doing that about, oh, seven, eight years now, as far as writing about health and fitness. And I've kept training and kept learning. So that's how I got here today.

Dan Ferris: You did things very differently than what mainstream health and fitness and diet sources tell us, right? It seems like these two categories – there's what to eat and how to exercise. And you did those very differently. It may sound difficult emotionally but you make it sound very simple. Like the things that you say to do... it's all so simple. How is it that we don't all know this already if it's so simple?

- D. Mangan: Well, first of all, yes, it is very simple. In principle it's all very simple. And so why don't we know this today? There are a number of reasons for that. Where do I begin? I think it starts back with the determination or the idea that saturated fat causes heart disease. So this was a big one back in the 1970s, and then around 1980 they came out with dietary guidelines for Americans. This just so happens to coincide with the start of our obesity epidemic. And I don't think that's a coincidence.

So what we've had here for the last basically better than four decades is health authorities telling us to avoid saturated fat, eat a high-carb diet, lots of fruits and vegetables, all that kind of thing. And Americans have gotten fatter and sicker during that time. Well, as a consequence of those dietary guidelines and the four decades of bad advice, we've got – for example, food companies all jumped in to make money off of what Americans are supposed to be eating. So in principle there's no problem with that. That's what they're supposed to do. But if the dietary guidelines were wrong then they've got everybody eating this way. And for food companies in particular, there's absolutely zero incentive for anything to change as far as telling people anything different.

As far as the academics, the doctors, the scientists, and so on that have been promoting this all along, there's no incentive either. If they were to come out and say, "Whoops, we got this wrong and it led to the obesity epidemic and a lot of people getting diabetes and becoming much sicker," they would massively lose face by doing this. They wouldn't have any authority anymore. People have built their careers on it. Dieticians are trained this way. Doctors are trained this way. In terms of – it's just very common where they tell people, "Stop eating as much meat and you've got to lower your cholesterol and all this."

So there are just no incentives for anything to change. There's really little money to be made in doing things the way that I advocate. The processed foods that most people eat – ultra-processed foods, to use the more technical term – are very profitable. And when you're talking about eating things like meat, fish, and eggs, vegetables, some fruit, this sort of thing – really whole foods, in other words – these things are not very profitable at all. Compared to let's say a box of cereal, which has pennies' worth of ingredients stuck in a box, fancy brand name and label on it, put on a grocer's shelf, and retails for $5 or something.

They're very profitable stuff. And it's not perishable. It can be advertised, fits in uniform sizes. There's all kinds of enticing things from a marketing point of view from that kind of food. Whereas let's say your meat and dairy and vegetables – they spoil. They don't typically have brand names associated with them so you can't market your product as superior to another's. It's basically a lot of supermarket labels. So there's just little incentive for things to change. So that's why I think: why don't we know this already? Why aren't more people saying the kind of things that I'm saying? I think that has a lot to do with it: that the incentives are not there.

Dan Ferris: That's a good insight. Incentive. So it's not just what to eat, though, right? It's what we eat and how often and how much, right? That's the one thing I've gotten from you that sounds really different from everyone else. All my life it's always been three square meals a day and snacks and all the rest of it. I just think that's normal for a lot of people. It's funny: I think I heard – it was either you or Nassim Taleb put it a certain way. You said, "We humans didn't evolve eating three meals a day and snacks." So that begs the question: what did we evolve to do? What should we do?

- D. Mangan: Right. We certainly didn't evolve that way. And grazing is the model that you're talking about there, with many meals and snacks and so on. And it's been recommended for quite some time now for various reasons which really don't stand up. But how have humans evolved to eat? How are we supposed to eat? Well, human beings certainly didn't get up in the morning and have a bowl of cereal first thing in the morning because it just wasn't there. I mean, in the course of our millions of years of evolution, we had to hunt or gather our food. And so they just wouldn't've eaten in the same way.

As far as actual scientific evidence goes, there has been a lot of interest in both intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating in the last couple of decades. And there's even more so now. And this shows that it's a solid strategy to get better health. Of course it depends on what you're eating when you are eating, but also not eating all the time is a healthy thing to do. How much you should do that – it's kinda speculation. But certainly, for example, if somebody eats within an 8-hour period of the day and doesn't eat in a 16-hour period, that's a solid strategy to get better health. There're many benefits from intermittent fasting. So, yeah, that is very different. People are just eating all the time now. It's almost come to be seen as heroic if you can go two hours without eating something. It's like you're starving or something.

Now, partly that's due to the kind of foods that people are eating. They're just not satisfying to hunger. So people get hungry and they get hungrier more often so they feel the need to eat. There's other aspects to it: for example, the fact that eating is just extremely convenient now. You can open up a box or a bag or the refrigerator or go to a fast food outlet or something like that. So that makes it real easy. But, yeah, people are just eating all the time and there's just no need. If human beings needed to eat that often, we would've never survived. Because that's not the natural condition: to have food available like that all the time. And then you see the results around us: epidemic of obesity and diabetes and so on, many other diseases. And those diseases are partly a consequence of eating all the time.

Dan Ferris: So, we have a guy here at Stansberry Research who does some biotech research, and he has been writing about this obesity epidemic. So I'm very much primed to hear your message and I'm nodding along with you as you speak. And he says – this fellow, Dave Lashmet, at Stansberry Research – he says, "We're basically built or we evolved to survive starvation." So eating eight times a day or whatever it is doesn't make a whole lot of sense. And when people like you and Dave put these things in such simple terms, I think, "Man, how the hell did we ever get here?" I guess we already covered that. But maybe, P. D., you could tell us right now – put it together a little bit. What does your day look like in terms of what you eat and how often and how much? Just a typical day for you.

- D. Mangan: OK. Sure. Well, it's 8:30 in the morning where I am, where I live, and I've been up for quite a few hours actually. I typically get up very early. And the only thing I've had so far is a couple of cups of tea. So I'll probably get something to eat maybe after we get off here at 9 a.m. Or I might wait till 10 a.m. And that would typically be something like a couple of eggs. And then maybe later I'll have something for a midday – I might pull out some leftovers from the previous night, which are typically meat and vegetables of some sort. Or I might have a cup of yogurt, something like that. And then later on in the day, say 6 p.m., I'll have my main meal of the day.

And that's typically – like last night I had steak and, I don't know, something on the side, I can't remember what, some kind of vegetable I think, glass of wine. And then I won't eat until – same deal. So I'm done eating at approximately 6 p.m. and then I won't eat till 9 a.m. or 10 a.m. the next morning. Sometimes actually later. Sometimes I won't eat at all until maybe noon. So that's real typical for me. On some days – for example, yesterday I did my weightlifting and that's a very hard training session so I eat right after that even though I train pretty early in the morning. So that's the exception: when I do eat in the morning is when I train in the morning.

So, yeah, that's a pretty typical day for me. I eat eggs, meat, some fish. I eat some dairy, some cheese, yogurt. I eat non-starchy vegetables. I don't eat a lot of fruit. I drink coffee, tea, and wine. And that about covers it.

Dan Ferris: Man, it sounds so simple. I have to say: it's beautiful in its simplicity. It really is. And I love the fact too that the point you made earlier about all the healthy good whole foods – they're not brand names. Nobody's making a huge profit margin off of this. I love that.

- Let's talk about the other half now. We've talked about diet. Let's talk about exercise. There's a very good popular diet narrative that you have talked about which you say is – it's terribly wrong. So does that same situation, that same type of narrative exists with exercise?

- D. Mangan: Yes, to a large degree it does. The difficulty with talking about exercise and putting it in such stark terms – in other words, the food narrative I think is just so completely wrong. But exercise – basically any kind of exercise is better than nothing, and most people are doing nothing. But the narrative that we have been told about aerobic exercise being somehow uniquely beneficial for us is mistaken. So aerobic exercise is good because, as I said, it's certainly better than nothing. But we're not being told about strength training, resistance training – weightlifting, in other words.

So, what happens to human beings as they age is that they lose muscle. This can be detected from a very early age. By the age of 30, loss of muscle can be noticeable. And it accelerates with each passing decade. So that by the time someone is quite old, let's say 80, they can have lost as much as half the muscle mass they had when they were young, say at age 20.

So this is really a disaster for health. Muscle is very important metabolically and for other aspects of health. More muscle is associated with longer life. And so we're not being told to do this. Less muscle is associated with diabetes, for example, and obesity. When people get older they become frail. People can lose so much muscle. Elderly people can have lost so much muscle that they literally can't get out of their own chair. And at that point they need help, which unfortunately can end up in a nursing home, something like that. So we're not being told to do this. Furthermore, weightlifting, or resistance training, to use a more generic term, if done properly does improve cardiovascular fitness. There's nothing unique about aerobic exercise that does this.

So, in my view, the exercise narrative is wrong. Let me add this. You were talking about my photos and how I look at age 65. And that's not the first time I've heard that. People say, "Wow," and I'm happy – I'm flattered and all that. But I consider it perfectly normal to look like that. It's not that difficult. There's nothing about – you don't have to spend hours and hours a week in a gym. You don't have to take performance-enhancing drugs or anything like that. It's just not that hard. It requires some dedication and some focus and some energy input for sure. But I only work out an hour a week. And anybody can do it.

Dan Ferris: An hour a week?

- D. Mangan: Yes.

Dan Ferris: And you look like that? That is amazing.

- D. Mangan: Yeah. I work out two 30-minute sessions a week. And those 30 minutes are very intense for sure. You've got to be focused. You've got to give it everything you got. But that's all it takes. You just don't have to become a gym bro to look good, to build muscle, to lose fat, and to be healthy.

Dan Ferris: Wow. An hour a week. That is very cool. I'm flabbergasted. I mean, the guy in that picture hasn't lost any muscle. He's 65. He's not losing any muscle. How long can that go on? Are you going to look like this when you're 80?

- D. Mangan: Well, I would hope so. There's certainly some diminution of the ability to build muscle with aging. But this decreased ability has been greatly exaggerated. And so that most people consider it as a given that they're going to be basically old and frail or something. Yeah, there is a decrease. I mean, if you consider, for example, world-class elite athletes, they peak in their early 20s, depending exactly on what event we're talking about. But they peak young. And even athletes just a few years older, say in their late 20s, can hardly compete with them. So that gives you an idea of when people peak for that sort of thing. But I'm not a world-class athlete by any stretch, and most people aren't. And you don't need to be one. So it's perfectly possible to build muscle and be fit into an old age.

Dan Ferris: I thought I saw something where you said stretching is totally unnecessary. But I must say: I look back at my life, and stretching has been – it's been a big help to me: doing specific stretches for specific muscles has really helped me a lot. At least I think they have [laughs]. I do them and I have less pain and then I get more pain if I don't do them for a while. So it's been a good thing for me to stretch. And also it's just something we do. It's something that mammals do. I see dogs and cats and lions and tigers and bears and they all stretch. So it must be normal for mammals. But what do you think of stretching? Do I make your point well enough? You tell me what you think.

- D. Mangan: Well, stretching could be useful for something in particular. Like for example if you have a particular pain or an injury or something like that that you need to get around, yeah, it can be useful. But as far as – my comment is more about warming up or doing stretching specifically if you're otherwise healthy. There's just no need for it. I mean, my warming up is – let me put it this way: my stretching consists of touching my toes a couple times, then putting my arms all the way up in the air over my head. That's about it. It takes me about 15 to 30 seconds.

And people who do intensive stretching, have a regular stretching session, and so on, in my view, they would be better off if they devoted time to lifting weights.

Dan Ferris: OK. Well, that makes sense. In other words, you don't need some big routine – you don't need to spend hours and hours in the gym doing anything, including stretching.

- D. Mangan: Right. There's a mistaken believe that you need to be lifting really heavy weights to gain muscle. And a lot of people subscribe to that belief. And so for those people who are lifting very heavy weights, they have to be very careful about warming up and so on. If you're going to deadlift 245 pounds or something like that, you need to be very careful. But you don't need to lift weights like that. Most of that, or a lot of that anyway, is done for ego purposes because people like to be lifting those heavy weights. If you're not doing that – the style of weight training that I do just really requires barely any warmup.

Dan Ferris: Very cool. I feel like your message is so liberating. When I started reading your Twitter feed and your website, I thought, "Oh, thank God. I can just eat the meat and eggs and fish that I really like and I can drink my tea and I can drink my wine and work out like an hour a week and not have to worry about it." People go to such trouble working out four, five, six days a week. They work out all the time. And they have these complicated routines and it's this big, involved, kind of, I have to admit, intimidating sort of thing. But actually this is a good next question. Let me just ask you about this. You're working out twice a week for 30 minutes and you say it's very intense. What specifically goes on in those 30 minutes? Are you just lifting weights until your muscles fail and that's the intensity of it? What's happening in those 30-minute sessions?

- D. Mangan: Yes. That's what's happening. Let me just follow up on your first thoughts there about people doing all that exercise, many hours a week and so on. Much of this comes from the mistaken belief that people are going to burn off their body fat by burning calories in the gym or outside the gym, anyway, with exercise. And this does not work. For many reasons. For one thing, you're not burning as many calories during exercise as you think. I mean, somebody was to go run five miles at a good pace, which is far more exercise than most people do at one stretch, you burn about 500 calories. And that includes the calories that you would've burned if you were just sitting still. You burn maybe 100 calories if you just sat there anyway. So you burn another few hundred by going running.

So it's really easy to make up that many calories afterwards in terms of eating. Exercise makes you hungry. And processed food is real easy to down the calories. So burning calories to lose body fat just doesn't work. You have to get your diet in order.

As far as what I'm doing during those 30 minutes, yes, I'm lifting weights with intensity. I go to momentary muscular failure, which means I do repetitions of an exercise in good form until I cannot do another repetition. And I only do one set of each exercise, not multiple sets like most people who do this in the gym do. And I move quickly to the next exercise. That's one reason it only takes me 25 to 30 minutes. In other words, no resting between exercise. Sometimes I might have to catch my breath or something after one of the larger compound movements like squats or deadlifts. But other than that, I just go to the next exercise and start in on it.

So that's what I'm doing. It is very intense. I've often said that if you don't have a sense of dread before you start your workout, you're probably doing something wrong [laughs]. I have that sense of dread every workout day. I'm sitting at my desk in the morning and I think, "Well, I've got to go work out." And I'm dreading it. Because it's a tough routine. But you do it in under 30 minutes and it's done. And of course you feel great afterwards.

Dan Ferris: Well, I'm very glad to hear that you dread it. Because guys like you who have a really clear message – you're a fitness guru. You're a legit diet fitness guru, and you have all these new and valuable insights. Guys like you can seem a little heroic. And to hear that you're as human as the rest of us – it's good for me to hear that.

- D. Mangan: Yeah. You know, I was just saying the other day that weightlifting – it never gets easier. It's not supposed to get easier. If it does get easier, you're doing it wrong. It's supposed to be just as hard years after you've started as it was in the beginning. Certainly your attitude changes toward it a little bit. I talk about that sense of dread. It is tough getting started. But I wouldn't miss it for the world. So that's how it is. But it's a tough workout.

Dan Ferris: All right. This is really cool. I've got one final question for you, P. D. Before I do that, I just want to make sure: people can find you on Twitter – I know they can find you there, and at your website, roguehealthandfitness.com. Those are the two places where we can find you, is that right?

- D. Mangan: Those are the two main places, yes.

Dan Ferris: OK. Great. So my final question for every guest, even when we talk finance, is the same thing – every guest, same final question. If you could leave our listeners with just one thought today, what would that be?

- D. Mangan: Everything you know is wrong [laughs]. No, that's not quite fair. Because that doesn't – it's not altogether true. What would I leave them with in terms of health and fitness? I would say: eat real whole foods, not ultra-processed foods, and do resistance training, and you'll be healthier than you could ever be doing anything else.

Dan Ferris: Perfect. Thank you for that. And thanks for coming on the show and talking with us today. I really appreciate it. I love your message. I have to say I've tried to make some of these changes in my own life, and it's going. It's not going great but it's going. So there's that.

- D. Mangan: Well, it was my pleasure being here. Thanks for inviting me.

Dan Ferris: You bet. Thanks so much for talking with us.

- D. Mangan: Bye now.

Dan Ferris: I hope you take P. D.'s message to heart. Like I said, it's liberating. It's so simple and so powerful. And it resonates with me. The first time I heard it I thought, "Yes, this is the health and fitness guy that I have been waiting for" – I wouldn't say my whole life, but certainly for years. A couple of decades of my adult life I've been – yeah, I just haven't known what to do. I haven't had any confidence about one thing or another. But he gives me a lot of confidence that his basic practices are very good. In fact, they're sort of like when I talk about the simple aspects of financial diversification: just hold your stocks and bonds and your cash and gold and silver and a little bit of bitcoin – those simple components, and he's sorta the same way, right? Just work out twice a week, make it very intense, do resistance training, and eat your meat and your fish and your eggs and simple whole foods and you're done.

I believe in simple messages that people have thought a lot about and kinda proven with their own actions. So, yeah. Great talk. I love this guy. All right. Let's take a look at the mailbag.

[Music plays]

You know how I'm always saying that I don't want this show to be too political? Because, after all, it's a finance show. And some politics is appropriate but it can get too much real quick, right? Well, maybe you're interested in politics. Maybe you're interested in American and global economics and politics. If so, you're probably going to be pretty excited to know that Trish Regan, the famous finance and political journalist, is now part of the Stansberry team. And Trish Regan has a brand new podcast. It's called American Consequences.

You can find it anywhere that you listen to podcasts: iTunes, Google Play, anywhere. Or you can just go straight to americanconsequences.com/podcast. And she's already had some huge names on the show like billionaire businessman John Catsimatidis and former U.S. Senate candidate Tom Del Beccaro. So check it out. It's available anywhere you listen to podcasts, or just go to americanconsequences.com/podcast.

[Music plays]

In the mailbag each week you and I have an honest conversation about investing or whatever is on your mind. Just send your questions, comments, and politely worded criticisms to [email protected]. Sometimes I get to read every word of every e-mail you send me. Sometimes you send me too many. This week I was able to read every word of every e-mail, and I will respond to as many as possible. We've got lots of good ones.

The first mailbag item today is from Jake H. And Jake says, "Hi, Dan. Great and thought-provoking podcast. Keep them coming. As a thought experiment, I'm going to assume the stock price of Tesla perfectly reflects the real value in the company. Assuming this is the case, the manufacturing plants and intellectual property hold a small fraction of the total value. So this can not just be a car company. In order to justify its value it must primarily be something else. As a data company, it seems that the data generated and collected is unique. Insurance companies might find some use for it. Unfortunately, this novel data will soon have competition from other manufacturers.

"As an energy distribution company, Tesla might have some significant value, both in the form on their charging network but also in the form of energy storage, thinking of the car primarily as just a big battery pack that has a secondary benefit of being able to drive around. I'm not sure it is an efficient form of power distribution. Driving batteries around is harder than running power cables. But it is possible. What do you think Tesla is, other than a scam? Cheers, Jake H."

You know something? I'm still going to say that Tesla is a car company. And my point here, Jake, is not that it doesn't have these other things going on. Because it does. Although at the moment I think there's like 1,800 Tesla charging stations and there's like 1680,000 gas stations. So it's in the early days of that. So I'm not sure if even at the current price – it just seems to be too much valuation for whatever constellation of things you call this thing. But I just want to be clear: to me, at this valuation – last time I looked it was like 26 or 27 times sales, losing 700 or so million a year.

At this valuation, my point is that you had better bake in that it's a car company, that it's in a highly capital intensive, generally low margin – they're not Ferraris, right? – generally low margin, highly competitive industry. Even though it's like the first big electric-only car company, I'm saying I don't think that matters. I don't think any of the stuff that you're pointing out ultimately matters because the valuation is so utterly extreme, right? I mean, Toyota's something like a third of the current valuation and it makes 20 times more cars in a year. So if Toyota makes 10 million, what does Tesla have to do, 20 million a year or 30 million? To justify the current valuation, maybe 100 million? I don't even know. But some number that is so utterly enormous that you know it's not going to get there in any amount of time and there's no way it's worth this much. But I like your thought experiment. It's good to do these things. Thank you for that.

Next comes Dan B. And Dan B. writes in and says, "Hi, Dan. I'm a longtime listener. Enjoyed your great surprises of 2021. But you neglected an important asset class so here's my No. 11 surprise. No. 11: in a news conference, Janet Yellen and Jay Powell introduce a new digital dollar to the United States. Cash will still be accepted by limited merchants but the digital dollar is now the legal tender of the USA and you might be refused if you want to pay by cash. If you want to pay by check or make a deposit in the bank by check, you can still do that but there will be a $5 surcharge for that privilege. Cash is out, digital is in. My two cents. Or should I say my two ounces or my two bits? Bitcoins. Dan B."

Thank you, Dan B. I mean, we're already just about there, right? The final step would be just sort of saying, "We're not using paper dollars anymore. There's no more cash." But we're almost there. So it's not crazy. But, to the real point, I don't think it would be that big of a surprise. I really don't. I think it's been headed this way for a while.

Adam B. writes in next, and he says, "Your show and guests have provided extremely valuable investing information and knowledge that help me understand more clearly. A good friend of mine, Jim, has turned me on to your podcast, which have turned into our weekly investment discussions, so thank you." Hey, you're welcome, Adam. Thank you. Adam continues, "I realize there's no crystal ball and I'm listening as you continue to discuss the immanent disaster bubble. What strategies can you suggest to protect our investments and what are the best methods to minimize damage if we dabble in some of the upward momentum, knowing there's a big meltdown on the way? What about stocks related to the vaccine and additional therapeutics that will be needed long term?

"A big concern I have is when I have discussions with younger investors who have never been impacted by a bubble or seen a major correction. I can only think this contributes to a larger bubble created by the large number of trading apps. I think MMT" – that is modern monetary theory – "and government spending will continue this upward trend and any correction will be similar to what happened in March: short. What message would you give them? Keep up the great podcasts. I cannot thank you enough, Adam B."

I see your point with MMT and government spending. I don't think that means all corrections will be short. I think it's possible to have an extended just say one-to-three-year bear market, as we've had multiple times over the past century. I don't think that's gone. I think it's typical of people at 10, 11 years into a raging bull to talk that way. But I don't think it's necessarily true.

As for your thoughts that the younger people who haven't seen a bubble and they're trading on these apps or contributing and making the bubble larger, I think that's approximately right. Although every bubble has its own characteristics. There was huge retail participation in the dot-com era, right? That was one of the big things: people were just in love with those stocks and with big-cap growth stocks in general and tech stocks in particular, and really helped push the market to its – until very recently its all-time highest valuation ever. So you're generally right but just a couple little tweaks there. In my opinion you're generally right.

Next comes Jeff K. And Jeff K. says, "In today's digest" – now, this was last week in the Stansberry Digest – basically he says in the digest I wrote, quote, "I've been warning you that stocks were expensive since May 2017. Since then the market has had a series of higher highs and lower lows." And he says that I should've said higher highs and higher lows. No, Jeff K., that's not true. If you look at a chart of the S&P 500 since the middle of 2017, you will not notice higher lows. You will actually see lower lows, right? So if you just look at – just get a three or maybe even four-year chart. It's crystal clear on both of them. Actually the three-year chart really. Because if you go four years, it is a little lower back there.

So if you look at the slight unpleasantness in the early part of 2018, there was a new high and then we hit a low, and then we went on to a new high late in 2018 in September before we had that big drawdown, and that was a new lower low, OK? Then we ripped up to February 19, the high before the unpleasantness of last year, and then we crashed down to a lower low than we saw back in 2018, right? So we got a higher high and a lower low. Now we're up at a higher high.

My point is: stocks are really risky these days, partly because the valuations are so utterly elevated. It's so elevated. That creates more risk. And I think the way things are going, if the trends of the past 10, 11 years reverse, we can get a lower low from here.

Having said that, remember one of my surprises from last week – it was that the market would make a higher high in 2021 and a lower low than last year. And the lower low – I have to say: that would even surprise me I think [laughing]. So it would sure surprise the heck out of everybody. So I did really mean to say higher highs and lower lows, Jeff K. But thank you for making me clarify.

Wayne B writes in and says, "Hi, Dan. I'm a longtime Extreme Value subscriber and enjoy your Investor Hour podcast. You've mentioned that many of the best pro-investor success is more about managing risk versus growth. Can you recommend a good book or other resource to help learn about this?" So, yeah, the first place you go is The Most Important Thing by Howard Marks. And there're three chapters on risk in there. Go there.

Then when you read that, read anything by Nassim Taleb. Probably start with Fooled by Randomness, and maybe The Black Swan. But read the others: Antifragile, Skin in the Game. And he's got a little book called The Bed of Procrustes. Read all five of those. Because he wrote them – they're a group. It's called the Incerto – or Incerto perhaps. Those are the books to read.

Next comes Robert H. And he says, "Hi, Dan, I really appreciate the obvious care and effort you put into the Investor Hour. Your guitar playing must suffer for the hours you so graciously spend on making this such a quality experience. I know that you say prepare, don't predict. However, resources of all kinds are limited. Preparing to me presumes some form of predicting probabilities." And he goes on to explain his position here and he says, "It seems to me that predicting and preparing are, perforce," that is, necessarily, "part of the same thing."

Sorry, I couldn't read the whole thing, Robert. But, no, preparing and predicting aren't really the same thing. Because you could be prepared – you should prepare for things that are unlikely. They're unlikely to happen. Bear markets happen. They're likely to happen but they're unlikely to happen any given year because they're relatively rare events, or they have been relatively rare events. They could be more or less likely in the future. We don't know. Looking into the future and saying you know is what you should not do, right? Prepare, don't predict.

I still stick by that and I don't agree with you. I don't think you have to predict. Because what have I said about diversification? I'm not saying you should hold plenty of cash, stocks, bonds, gold, silver, and bitcoin because all those things are going to go up together. I've said it for the opposite reason: I expect them to perform differently at different times and overall to preserve and grow wealth over the long term. So I'm sticking with that. But I'm glad you asked.

Next comes Romeo B. Romeo says, "Happy New Year." Happy New Year to you, Romeo. Thank you. Then he says, "The reference to circuit breakers in the latest episode got me thinking about strategies for buying assets on the cheap in the event of a market panic. Instead of just waiting to buy low, why not place a limit buy order at a level well below market and see if it gets filled? Might seem ridiculous to bid $3 for a stock that currently trades at $10. But if I can see a scenario where it drops to $5 then I could be the only buyer when everyone else is saying, 'Get me out at any price,' and the market suddenly becomes illiquid. Do I live in dreamland or does that idea have any merit? I don't expect to be able to buy Google for $100 a share but maybe this could work for some of the more thinly traded stocks or high-yield bonds. All the best for 2021, Romeo."

Thank you, Romeo. All the best to you too. This is called stink bid. When you place one of these bids it's called a stink bid. There are circumstances under which you might want to do it but in general the problem is: what if that $10 stock goes to $0.50 instead of $3 or – it's going to hurt. You're setting yourself up there and it may not be necessary. If you just keep an eye on things, you can set alerts through just about any kind of a trading app or a brokerage account, online brokerage account, that will tell you when these prices have been hit.

So I would just set the alert for that super-low price. Set the alert for minus 50%. So on your $10 stock you do an alert for $5. And then you can go in and look at the situation and say, "Hm. The company says they might declare bankruptcy. Maybe I won't buy it." You know what I'm saying? There're circumstances under which things get cheap all of a sudden for a reason. So just a few thoughts.

But people do what you say. I don't think they do it – they do it under specific circumstances in my experience, right? They find a specific stock that they're highly likely – they think it's highly likely to turn out well and they want to own it but they want to pay a lot less. It's illiquid maybe so they see the action is very volatile so then they place the stink bid well below market. So, yeah, it's a thing that real investors do. Good question.

Next and last comes James W. OK. So this – I talked in my quote of the week about Martin Niemöller, the German priest. He's our quote of the week, and I said this was from one of our listeners, and our listener is James W. And James W. did his own version of that very famous quote that I read you by Martin Niemöller. And these are the times to do this. And you did a good job, James. I'm going to read it to everybody. I think you did a really good job. So here's James W.'s version of Martin Niemöller's famous quote.

"First they demonetized certain voices on social media and I did not speak out because I did not make a living from YouTube. Then

they did soft deplatforming, controlling who could see what, and I did not speak out because their algorithms were invisible to me. Then they started taking public events as provocation to silence prominent people and I did not speak out because I am ordinary. Then they deleted, without provocation, every voice not speaking quote 'the community standard,' unquote, and I did not speak out because I could still get information. Then they deleted me, and no one spoke out for me because no one could." Thank you for that, James. Great job. Excellent quote for our time.

That's another mailbag and that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. If you want to hear more from Stansberry Research, check us out at americanconsequences.com/podcast. And do me a favor: subscribe to the show on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, help us grow with a rate and a review. You can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Our handle is @InvestorHour. Also follow us on Twitter where our handle is @Investor_Hour. If you have a guest you want me to interview, drop us a note at [email protected]. Till next week, I'm Dan Ferris. Thanks for listening.

[Music plays]

Announcer: Thank you for listening to this episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to investorhour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail: [email protected].

This broadcast is for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

[End of Audio]

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.