Where to Find Big Gains in Resource Stocks

In This Episode

In the final stages of the bull market, thoughtful investing is typically replaced with reckless speculation…

And today, we’re seeing warning signs in nearly every corner of the market…

Investors everywhere are throwing caution to the wind in hopes of finding the hottest tech stock, SPAC offering, or cryptocurrency that’ll help them get rich quick…

So that’s why this week, Dan is bringing the listeners back down to Earth by focusing on a corner of the market that fuels nearly every other industry, but has recently been forgotten by most of the financial media…

On this week’s episode, Dan invites Rick Rule of Sprott Inc. onto the show to talk about natural resource investing.

Rick began his career in the securities business in 1974 and has been principally involved with natural resource securities ever since. Over his long career, Rick has originated and participated in hundreds of debt and equity transactions with private, pre-public, and public companies.

Today, Rick is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished natural resource investors on the planet.

During their conversation, Rick talks about how stepping down from his position as managing director and president at Sprott has allowed him to focus more time and energy on researching potential investments in the resource space.

Rick and Dan discuss where he sees opportunity in the resource market today, including a handful of stocks from the other side of the globe that he believes are currently trading at steep discounts.

If you’re okay with some riskier, higher upside plays, Rick shares the names of a few stocks which he says are “the cheapest resource stocks on the planet…”

Then on the mailbag this week, Dan answers a couple great questions from listeners who have written in…

One listener asks Dan his thoughts about a recent quote from Stanley Druckenmiller, where he discusses the possibility of the dollar losing its status as the global reserve currency…

And another listener shares what he believes is the real motivation behind the new E.S.G. investing trend….

Dan gives his thoughts on these questions and more on this week’s episode.

Featured Guests

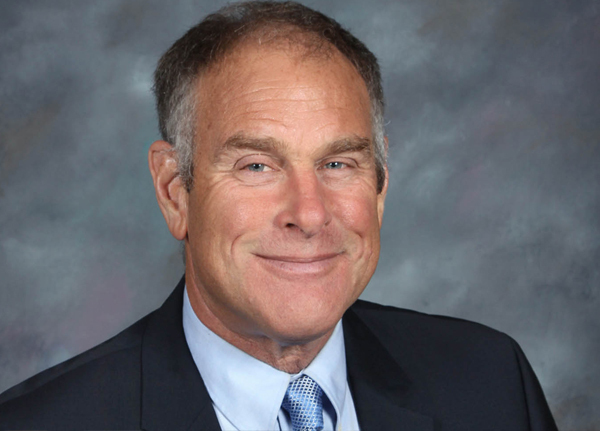

Rick Rule

President & CEO, Rule Investment Media

Rick Rule is the president and CEO of Rule Investment Media. He began his career in the securities business in 1974 and has been principally involved in natural resource security investments ever since. As a world-renowned resource investor, Rick has specialized in mining, energy, water utilities, forest products, and agriculture. He also has originated and participated in hundreds of debt and equity transactions with private, pre-public, and public companies. And he served as founder of Global Resource Investments for nearly two decades before leading Sprott U.S. for 10 years as president and CEO.

Episode Extras

1:31 – He called the Dot-Com crash and the housing bubble… Now Dan examines the latest warning from legendary investor Jeremy Grantham…

3:40 – This week’s quote comes from an interview Jeremy Grantham did with Business Insider… “This is pretty bad on a very broad front… We will have to live with potentially, possibly, the biggest loss of perceived value from assets that we’ve ever seen…”

7:49 – This week, Dan invites Rick Rule onto the show. Rick began his career 47 years ago in the securities business and has developed a large following thanks to his vast expertise in many resource sectors, including agriculture, alternative energy, forestry, oil and gas, mining, and water. Over the years, Rick has participated in hundreds of debt and equity transactions with private, pre-public, and public companies.

10:25 – Dan asks Rick what he does to keep busy since stepping down from his position of managing director and President at Sprott USA…

16:10 – “It seems that most of the impact of regulation is to constrain the flow of information from honest people to honest people, around the vainglorious hope that you can protect investors from their own worst instincts…”

21:41 – Rick explains why he believes insurance is the purest form of risk arbitrage out there…

30:09 – Dan asks Rick if he sees any big opportunities in the resource markets… “Where are the mispriced risks in the resource sector today?”

31:45 – “If you look out either 5 or 6 or 7 years… either the price of uranium goes up or the lights go out. My suspicion is that the price of uranium goes up…”

33:37 – “Many people, including some Stansberry subscribers, believe that the gold bull market is over… I would argue that gold bull markets have a substantially greater duration…”

36:33 – Rick shares the name of a few relatively unknown resource companies he says are worth looking into… “…a couple Australian names: Northern Star, Evolution Mining are both attractive to me…”

40:28 – Rick shares a riskier, higher upside play… “For your listeners who have the courage to take a lot more political risk, and deal with a lot more financial opacity, the Russian resource stocks are the cheapest resource stocks on the planet… names like Lukoil and Gazprom…”

44:36 – As their time winds down, Rick leaves the listeners with one final thought, “Any of your listeners who would like to know the way that I think about natural resource stocks which matter to them, which is to say the ones they own, can access this… if you go to our website: SprottUSA.com/rankings and enter your natural resource holdings… I will rank those stocks 1 to 10, and I’ll comment on individual issues where I think my comments might have value…”

49:49 – On the mailbag this week, Dan answers a couple great questions from listeners… The first listener asks Dan his thoughts about a quote from Stanley Druckenmiller about the possibility of the dollar losing its status as the global reserve currency… Then another listener shares what he believes is the real motivation behind E.S.G. investing. Dan gives his take on these questions and more on this week’s episode…

Transcript

Broadcasting from the Investor Hour Studios and all around the world, you're listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour. [Music plays] Tune in each Thursday on iTunes, Google Play, and everywhere you find podcasts for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive at investorhour.com. Here's your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value published by Stansberry Research. Today we'll talk with my good friend, Rick Rule, which I haven't done in way too long. Get your pen and paper ready. Rick will give us several names of stocks he likes. This week in the mailbag, questions and comments about the U.S. dollar, Treasury rates, Stanley Druckenmiller, climate change, and more. In the opening rant this week, the guy who called the dot-com and housing bubbles is chiming in again, and you definitely want to hear what he's saying because it is huge. That and more right now on the Stansberry Investor Hour.

So who is this guy? Who's the guy I'm talking about who called the dot-com and housing bubbles? Actually, he's called a lot of bubbles. He was around during the Japanese stock market bubble, and he was really bearish about that too. And his name is Jeremy Grantham, and he has a firm called GMO in New York. Last I looked, they were managing like some number like $18 or $20 billion. It's probably triple that now. And I don't know. But they manage money. They manage a lot of money.

And they put out a lot of stuff on GMO.com. There's a lot of good research to read. But just recently in a Business Insider article, Grantham said, you know, "This is eerily like 2000." Meaning the current episode looks a lot like the dot-com bubble to him. And he's got these four – they said four indicators in this article. But it's really four markets. You know? Four huge asset markets. Stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities. And he looks at all of those and he says, "You know, they're all flashing warning signs. They're all telling you that they're dangerously overheated."

He thinks housing is dangerously overheated. Most of the narrative I read in the press says, "You know, yeah, we're around the 2006 peak in housing prices or whatever." But as they always say, "It's different this time. You know, we're safe here. It's safe that housing has become this overheated." And most people say, "Well, it's an inventory problem due to COVID." But all of these things concern Grantham. He says, "Stocks are expensive. Bonds are expensive. And real estate is expensive."

And commodities have soared out of sight. I mean, if you look at a chart for lumber or copper, it's crazy. And other things. Corn is one of them, I think. So, you know, he looks at all this. And the quote is – and this is my quote of the week, so I'm just kind of mushing the rant and the quote of the week all together here. It's part of this article, this Business Insider article where Grantham made his comments.

And the quote of the week is a little scary. And I think that's appropriate. So the quote of the week is, Jeremey Grantham quoted in Business Insider. He said, "This is pretty bad on a very broad front." Right? He said stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate. Right? That's a pretty broad front. That's all the major asset classes. "This is pretty bad on a very broad front. We will have to live potentially, possibly, with the biggest loss of perceived value from assets that we have ever seen." Well, that just makes sense, right?

If you're saying it's the biggest bubble you've ever seen because the excesses are hitting all four of these asset categories, well then the aftermath would be the biggest loss of perceived value ever seen, you know, if we get the correction. And the correction – and Grantham has talked about this elsewhere. You know, the correction doesn't go back to reasonable prices. It tends to go way back below what's reasonable. It becomes an extreme to the upside. And the more extreme to the upside, the more extreme to the downside. And he says something like almost exactly like that in this article. I can't find it.

But it doesn’t matter. That's the point. The point is, the worse it is to the upside, the worse you should expect it to be to the downside. And who else have I quoted to that effect? Well, John Hussman from hussmannfunds.com, who tracks the valuation of the S&P 500 based on historical measures that have predicted very well what future returns have been. So based on those measures, he's saying you're going to get the worst 10- to 12-year performance ever out of the S&P 500. So, you know, people who are experienced with this stuff and understand it and have a track record with it are... and Hussman called the – man, he called the dot-com bust like nobody's business.

He actually nailed the exact percent loss of the Nasdaq... predicted it before it even started. So these guys have somewhat of a track record with this stuff. And Grantham has a great one. His firm has studied a couple dozen of these bubble events. They're saying this thing is the worst one. Right now, the moment we're living through is the worst bubble ever in terms of what you can expect for future returns from these various asset classes. And for you and me, let's face it. Especially stocks, right? That's our main beat around here.

So wow. That's my rant. That's my quote of the week. I hate to leave you on a sour note, but sometimes that is appropriate. Sometimes the thing that I should be doing is making you worry a little bit. And so, I’m going to leave it right there. Be worried. There's something to be worried about. All right. Let's do it. Let's talk with Rick Rule. Let's do it right now. [Music plays and stops] Every week, I tell you I'm the editor of Extreme Value published by Stansberry Research. But I don't usually say anything more than that.

Well, to my dedicated listeners who are looking to find incredibly valuable long-term investments, I'll tell you right now. My Extreme Value newsletter is a monthly publication that focuses on buying safe, cheap stocks only when the price is right. And I'm not overexaggerating. Extreme Value picks have earned one of the most impressive track records in the industry. Mike Barrett and I spend hundreds of hours each month poring over balance sheets and SEC filings to find stocks trading at huge discounts to their true worth, giving subscribers a large margin of safety on every pick.

You can learn more about that or sign up for the newsletter at investorhourdan.com. So you can support the show and find some of the most profitable ways to invest all at once. Investorhourdan.com. Check it out. [Music plays and stops] Time for our interview today. And I'm really looking forward to this one because today's guest is my friend Rick Rule. Haven't talked to him in a while. Rick began his career 47 years ago [laughs] in 1974 in the securities business and has been involved in it ever since.

He's known for his expertise in many resource sectors including agriculture, alternative energy, forestry, oil and gas, mining, and water. I think we should talk about reinsurance too. Maybe we'll do that. Mister Rule is actively engaged in private placement markets through originating and participating in hundreds of debt and equity transactions. Rick, welcome back to the show.

Rick Rule: Dan, a pleasure to be on with you. It's been too long, in fact.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So your life has changed quite a bit, starting with an announcement at the end of February which became effective mid-March. You stepped down from two roles at Sprott. I guess you've got several hours a week to do with as you please now.

Rick Rule: Yeah. In a sense, it was a pretty amazing pay raise in the sense that I've got about 30% of my time freed these days. The good news is, I guess if you've been reasonably successful intellectually and financially in your life, at a certain point in time you have the freedom to do more of what you enjoy and less of what you don't enjoy. And certainly, I didn't enjoy some of the managerial responsibilities I had.

I think it goes without saying that I didn't enjoy the regulated environment that I and anybody else in the securities and investment business endures. So shedding those two roles and being able to refocus on securities analysis, which I've always liked, and education and communication, which I also like, has been a real blessing to me, Dan.

Dan Ferris: I bet. I would love to be a fly on the wall in your office at home to see what you're up to, day by day and hour by hour.

Rick Rule: Well, this time of year it hasn’t changed much. This is annual report season.

Dan Ferris: I see.

Rick Rule: So, in retirement, I've been working 12 to 14 hours a day doing the green eyeshade stuff that I like so much, much to the chagrin of people who misinterpreted what my retirement might look like.

Dan Ferris: Oh, I see. Yeah. [Laughs] Well, you know, you love what you do. So I guess you're continuing to do more of it. But I noticed that, you know, in the press release, it said you're stepping down as managing director and, what, president of Sprott USA – and still, you're going to be a Sprott director, and you're going to be an advisor on investment vehicles, and advisor in an ongoing marketing capacity it said. That sounds like a lot of work to me. That doesn't sound like retirement.

Rick Rule: Well, if you describe work as a vaguely unpleasant thing that you do to sustain your life, I don't work at all. I do things that amuse me, and I allow other people to benefit where convenient to them and to me. I am very active, but there's no part of my activity at present that isn't pleasant. Prior to my retirement, I couldn’t say that.

Dan Ferris: That's right. So you remind me of Buffett. You know? "If it didn't pay a dime, I'd still do exactly the same thing."

Rick Rule: Yeah. That's disingenuous for both he and I to be frank. I've actually said that in the past. "If it didn't pay so well, I'd do it for free." That's not strictly speaking true. But, like Buffett, I am delighted with my circumstance in life. He has generated more utility over his life than I have with mine. So he gets to play the game at a different level.

Dan Ferris: Well, you know, you haven't done too shabby as far as I can tell. I know I'm pretty impressed.

Rick Rule: I have no apologies, Dan, and no complaints. It's treated me very, very, very well. It's nice the – it's nice that the outcome has been as it is. I've really enjoyed the ability to up my game in terms of communications, mentoring, and teaching. Which is to say, doing interviews like this. There were questions that I couldn't answer in my prior capacity, either as a consequence of Sprott's other interests or as a consequence of regulatory constraints. And that caused some frustration.

And those frustrations are largely gone, which is lovely. As an example, I couldn’t, in an interview like today, talk about Sprott products or Sprott. Which was sort of an odd constraint. There weren't many people around who knew as much about those topics as me, and I was constrained from a regulatory point of view from answering honest and open questions about a subject that I both knew about and cared about.

Dan Ferris: So, Rick, were the regulatory constraints – I don't think I understand them completely. They're on the officers of the company and not the directors?

Rick Rule: Well, I'm taking the view, Dan, that I am no longer constrained by Sprott's compliance regimen – that I have to disclaim my remarks if they seem favorable, by way of saying that I am still the largest shareholders and, thereby, benefit indirectly to the extent that an audience purchases Sprott products or services or indirectly purchases Sprott Inc stock itself. And I think that those disclaimers are fair. Before, I was constrained about offering up a viewpoint on Sprott products because it was alleged to be – as an example, with our physical trusts – marketing while we had an evergreen prospectus in place.

And as a securities licensed person, anything that FINRA deemed to be marketing had to be preapproved by them. Obviously you can't preapprove an interview. So I've taken the point of view that since I am no longer a licensed person – that is to say, no longer a stockbroker – that I am no longer governed by that aspect of the FINRA regulations and that I'm governed rather by the full and fair disclosure doctrine, which says that [laughs] – reasonably – I have to use my best efforts to tell the truth. Which I don't think is an unrealistic constraint.

Dan Ferris: I see. And no longer a broker, having stepped down as your role as president and CEO of Sprott U.S. Holdings. Do I have that right?

Rick Rule: Yes. That is correct. I've also given up my stockbroker's license and my stockbroker's supervisory licenses. So I've kept – or am reapplying, frankly, under a different guise to continue my registered investor advisor affiliation.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. I hope the reader – or, I’m sorry, the listener – will forgive my fascination with these details. It has always fascinated me that a guy like you... and the reasons, you make them clear. But you're in this business that is just so meticulously and heavily regulated. The rewards must be pretty darn good, is all I can say. [Laughs]

Rick Rule: Well, I love what I do. You know? I love interacting with people. I love securities analysis. And in fairness, Dan – this will shock you – most of the time when I meet the employees of the regulatory organizations, I like them. They exist themselves in a world that has so many constraints that, despite the fact that they're good people, they seldom can do good jobs. Which is unfortunate. It seems to me that the apparatus of regulation is designed to protect the public from a few bad apples who pay no attention to regulation whatsoever. [Laughs]

It seems that most of the impact of regulation is to constrain the flow of information from honest people to honest people around the vainglorious hope that you can protect investors from their own worst instincts and from some of the worst elements of humanity. Something that I believe is futile. I actually believe that investors would be better served if they understood that nether FINRA nor the SEC can protect them and they had to do the work to protect themselves. But that's maybe a conversation for a different day.

Dan Ferris: Well, it might be. But I've made the same point in, you know, Stansberry Digest and in the newsletter I write and on this show. And I agree. I gave that example. I forget who the guy was. I think it was an insurance company executive or somebody who said, "You know, he could bring all traffic accidents to a halt simply by getting rid of all the safety gear in the car and replacing it all with a six-inch spike sticking out of the steering wheel."

He said, "There would never be so much as a fender bender. It might take four hours to get to work every day, but there would never be so much as a fender bender." And I feel like there's a point to be made in not pretending to protect the investor from the full brunt of his decision. You know? This purporting to protect him is – it works against him. I agree with that.

Rick Rule: And certainly the economics of regulation is interesting. Warren Buffett, who is of course no foe of government or regulation, has pointed out that the consequence of the Enron fraud was a circumstance where fraudulent activity on the part of Enron officers and directors cost shareholders and customers somewhere between $70 and $80 billion. And Buffett made two points. First of all, the impact of that was the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, which costs public companies – and hence their shareholders – in excess of $100 billion a year.

In other words, the cure on an annual basis exceeds the cost on a total basis. But probably more importantly, fraud was illegal before Sarbanes-Oxley. In other words, what we had was a regulatory failing, not a market failing. And the idea that we double down on regulation and imposed $100 billion in annual cost to the economy to cure a problem that was already covered by existing regulation cost between $70 and $80 billion tells you something about the arithmetic of securities regulation.

Your other point, of course – deluding investors into believing that FINRA or the SEC actually protects them from fraudulent activity flies in the face of Madoff, who is alleged to have pilfered some number in excess of $10 billion net. And for much of the time that he was alleged to have done that, he was the president of FINRA. In other words, the regulator. So truly, it would appear that society hired a wolf to be the shepherd.

Dan Ferris: I think they do that a lot more often than they think.

Rick Rule: Anyway. We've probably disenfranchised enough of your viewers now, Dan.

Dan Ferris: I know. I know. It's my fault. I opened this can of worms. And so, I will close it right now. And let's talk about something else, which has been on my mind as soon as I knew we were going to talk to you today. You and I were talking once. And it was within the past four or five years. And we were talking about the resource business and mining as a crazy, horrible business – highly capital-intensive, extremely cyclical, very difficult. And you brought up reinsurance. And if I'm not very much mistaken, you had said something like, "Man. If I'd known about this 40 years ago, I would've done this and skipped right past mining." Because you liked it that much.

Rick Rule: And I've refined my views. I probably would've confined myself to reinsurance around extractive businesses. In other words, I probably wouldn’t have chosen to practice reinsurance as a generalist because I don't think that you understand enough about the risks that are specific to an industry. I'm interested – as you know, Dan – both financially and academically in the concept of risk. I'm interested in mispriced risks.

As a contrarian, I'm interested in circumstances where society either believes an activity to be riskier than it is or doesn't believe it to be as risky as it is. The concept of risk works both for me on the insurance side – which is really a form of lending. You are lending your balance sheet to a fee for somebody who's engaged in activity that he or she believes is risky. I'm interested in risk both from that point of view – which is to say, as a lender's point of view, as an insurer's point of view – and I'm interested in it from an investor's point of view.

I'm looking at the delta, if you will, between perception and reality around risk on both sides of the ledger. So from my viewpoint, insurance is the purest form of risk arbitrage. And in that sense, it's very, very interesting to me. Insurance interests me too because of my observation from reading the Berkshire Hathaway annual report for many, many, many years that as a consequence of the reinsurance business, Buffett became a prior taxpayer.

And I think being a prior taxpayer is both arithmetically sound and patriotic. Why feed the beast? When I say a prior taxpayer, what you'll notice when you look at the Berkshire Hathaway annual report is that the float which he makes so much of, that that pool of capital which is neither debt nor equity but contributes to return on equity is really the excess of premiums received prior to clients paid.

And it's this wonderful tax-free mechanism. What you see with insurers, but particularly reinsurers, is that when they put longtail risks on the balance sheet, they are allowed to reserve against those risks. In fact, they're encouraged to reserve against those risks because the political class and the financial class wants well-capitalized insurers so that the liability doesn’t become socialized.

The upshot of that is that if you take – as an example $1-billion contingent liability over a long period of time and you're receiving, say, $15 million or $20 million a year in premium – you can establish a risk reserve against that $1 billion potential liability of, say, $150 million and use that reserve not only to shelter the premiums that you received from immediate taxation but also to shelter earnings from other parts of the business as long as that reserve – the cash in that reserve, the so-called deferred tax liability – isn't either salaried out or "dividended" out. And that's an enormous advantage. The idea that you can shelter other sources of income for a very long period of time – in fact, for as long as you keep growing your insurance business – is attractive to me, Dan.

Dan Ferris: So the reserve against that – we just hypothetically said – $1 billion of contingent liability over a very long time and hypothesize this $150 million reserve... That is a tax shelter for other risks as well?

Rick Rule: Correct. Understand that that reserve – and I'm simplifying this – needs to be maintained in investment accounts. It can't be 'dividended' out or salaried out. In other words, the reserve has to be there to be reinvested, which is precisely what Buffett wanted to do. [Laughs] He didn't like the double taxation associated with dividends. And he liked the idea that he could defer current income and ultimately, perhaps, pay the liability later by allowing his shareholders to sell the stock. In other words, converting current earned income to deferred capital gain. An extremely efficient tax arbitrage.

Dan Ferris: I could spend more time digging into this, but I think I’m going to let it go. But it sounds very cool to me. It sounds like the most massive corporate 401(k) you could ever sort of imagine.

Rick Rule: You know, a 401(k) is all about deferring current consumption in favor of your future. And that's precisely what float is about.

Dan Ferris: Right. And that, too – isn't that the source of leverage which people don't normally talk about when they use Warren Buffett's name?

Rick Rule: Well, it's a beautiful form of leverage. It is actually, probably, a form of debt. Because at some point in time, Buffett will be confronted with some fairly large claims. So, when I say debt, what Buffett has done is exchanged the financial strength of Berkshire Hathaway, or lent the financial strength of Berkshire Hathaway, on a contingent basis in return for what would normally be considered an interest payment that's in fact insurance premium.

This pool of capital, this float, this deferred tax credit – depending on how you view it – doesn't show up as a formal recourse liability. Which is to say, although it feels like debt to me, it's a contingent debt. It's a floating debt. And it isn't equity. The product of it can become equity, which is to say that if Buffett has this pool of effectively costless capital – when I say costless capital, it means if he underwrites correctly that his insurance premiums are sufficient to pay his net claims.

Which means that the float, the premiums received before the claims are paid, ends up being a capital pool which is costless, to the extent that you have a $100 billion pool of costless capital and you're enjoying 10 or 12% return on capital employed. What that means is that between $100 and $120 million a year can flow into equity accounts. And in the wonderful machine that is Berkshire Hathaway, as the policy liabilities build, the capital that is generated is also sheltered in similar fashion. A truly astonishing pre-tax/after-tax capital pool.

Dan Ferris: And as Buffett likes to point out, not merely costless but negative cost – paid to hold it.

Rick Rule: Often, often negative cost. Now, that has to do with his prudence as an underwriter. When things go bad for Buffett, they go bad in relatively large numbers, unless you compare the number against the size of the capital pool that's being pledged. What's interesting about float, Dan – and I'm really sorry to beat this apart. I thought we were going to talk about resources. But that's OK.

Dan Ferris: I know.

Rick Rule: What's really interesting about this is that Buffett, in the last two years, with a period of negative real interest rates, has talked about the fact that the float is beginning to have cost. Which is to say if your expected return on capital employed in debt generates a negative return, that $100 billion – if that's the right number for the float – rather than giving you a positive return can give you a negative return.

Meaning, as an example, if you invest some of it in the U.S. 10-year Treasury and you're getting 160 basis points in a currency that's debasing itself by 175 basis points a year – if then the interest rate goes up and the capital value of your 10-year bonds declines, then as a consequence of your investment decision, the float does have cost. Now we're probably way deep in the weeds for people. But it's interesting to note – it's interesting to note that the float which has been valued... which has been regarded as such a valuable part of insurance businesses increasingly requires investment skill... whereas, 15 years ago, it only involved the ability to buy intermediate-term bonds.

Dan Ferris: Right. If I could sum this up – maybe – we're not just talking about float. We're talking about float in Warren Buffett's hands for 50 years. Right? I mean...

Rick Rule: Correct. Correct.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So let's just get that right. So we should move onto resources because when people hear your name, they think resources. And you did talk about how much you love mispriced risks. And that becomes my question. Where are the mispriced risks in the resource sector today?

Rick Rule: Well, I would say primarily they were 18 months ago... There's much less mispriced risk in the market now. I would argue in the lower end of the market, in the sub-500-million market-cap space, which is ironically the area of my greatest competitive advantage. But the market is, by and large, ahead of itself. Which is to say, as the price has gone up and the sector has become more popular, it's become much more risky. People have a difficult time understanding this.

But if a stock goes from $1 to $2 with no change in the underlying fundamentals, you're happy that the price has gone up. It's precisely half as attractive arithmetically. And that's beginning to happen. There are areas – which is to say that there are commodities – which are still underpriced. Probably uranium would be the classic example. It's absolutely necessary for the ascent of mankind because it's very efficient baseload power, and it's also, in today's climate, non-carbon-generating power.

It also costs the industry, fully loaded, somewhere between $50 and $60 a pound to make, and they sell it at least in the spot market at $30 a pound, losing $20 a pound and, of course, trying to make it up on volume. The arithmetic proposition, then, is if you look at five or six or seven years, either the price of uranium goes up or the lights go out. My suspicion is that the price of uranium goes up. Had we been talking about this a year ago, I would've said that access to this proposition through the equity of uranium producers or junior uranium developers wasn't merely cheap, it was, to quote a Buffett phrase, "felony cheap." It was so cheap it was stupid.

That's no longer the case. I can make an excellent valuation case for some of the larger uranium producers, particularly Kazatomprom, if one is willing to take the risk of investing in Kazakhstan. I believe, too, that if the price of uranium goes up in the time frame that I say it will, that the juniors will do extraordinarily well. But the price of the juniors relative to the current price of uranium – which is to say $30 a pound – is no longer felony cheap. These stocks have all doubled and tripled in the last year.

But that's probably the most egregious example. A different place that I'm seeing good absolute – and relative value, however – is in the mid-cap gold producers. I should preface this by saying that I am a gold bug. I believe that the political and social circumstance that we see ourselves in today, particularly quantitative easing, which you and I would call counterfeiting, debt and deficits – which debases the currency – and, in particular, negative interest rates are tailor-made for an increase in gold price.

Many people, including some Stansberry subscribers, believe that the gold bull market is over. They believe that three and a half years into a gold bull market, the gold bull markets only last four or five years and it's over. I would argue that gold bull markets are a substantially greater duration. I've been through two. One was 1970 to 1981 – 11 years. The other was 2000 to 2011. 11 years.

So I suspect that the duration on this gold bull market is greater than people think. And I think the dimension is greater than people think too because gold and precious metals move when people are concerned about the debasement of the currency and the impact that that has on the purchasing power of their savings. And anybody who isn't concerned about quantitative easing, debt and deficits, and negative real interests rates I believe needs to have their head examined. So I'm constructive to higher precious metals prices and, hence, the higher prices around companies that produce them. The very large producers have continued to enjoy inflows of generalist funds.

And I think that they're probably fully priced at $1,750 gold, although I just think that they discount extensively higher gold prices. The juniors, too, as a class, have moved too far too fast. Remember that most of the juniors will never actually produce any gold. And if the price of something that you don't have any of goes up, it shouldn’t really impact in your fortunes. But the mid-cap producers, the single-asset producers – the companies producing between, say, 500,000 ounces and 1 million ounces a year – are, by the metric that I like to use to value the buy, the cheapest that they've ever been in my career.

That metric is the net present value of cashflows from proved developed, producing reserves at the forward strip price relative to enterprise value – enterprise value being market capitalization plus debt minus redundant assets and cash. I realize that's a slavish formula, and people want rules of thumb. But that's not what an old credit guy like me does. So by the metric that I have just tried to explain to your listeners, I would suggest that the mid-cap gold producers are probably the cheapest that they have been in my career by the metrics that I use to measure them. So I think that's an attractive sector.

Dan Ferris: Can we trouble you for a name?

Rick Rule: Yeah. There's a few names. Understand that people need to do their own due diligence. This is for investment purposes. Understand, too, that if I like a name, I invariably already own it. And so, in this instance, I'm talking my book. But certainly names like Endeavour Mining, which has enjoyed tremendous growth in Africa, is an attractive name. A couple of Australian names: Northern Star, Evolution Mining are both attractive to me. One that I think is a special situation – well, a couple that I think are special situations.

But one that is particularly unloved now – and in fact, I used to dislike it – would be SSR Resources, which has made a practice of buying up cash-starved producers from other companies, recapitalizing them, and growing. They're digesting an acquisition that was a merger of equals. And the consequence is that the share register is changing. And it's one of the real examples of upcoming operational synergy, price-to-discount to the net present value of future cashflows for structural reasons. So those are the sort of names I'm attracted to.

Dan Ferris: Nice. OK. You're up to five names. I think that's about the second-highest total of any guest we've ever had.

Rick Rule: Well, it's interesting. You know, we probably should've visited it 18 months ago when, if regulation had allowed me, I could've given you 50 names. We're not there now.

Dan Ferris: Right.

Rick Rule: I'll tell you one other sector, however, Dan, that might amuse you. The Canadian oil and gas sector is felony cheap. It's felony cheap for a reason. Their free cashflows got decimated both by declining demand for oil as a consequence of, of course, COVID-19 but also, in Canadian parlance, a series of own goals. Which is to say, ironically, that the federal government of Canada is doing their level best to destroy their domestic oil and gas industry for political reasons. The sector is just too cheap at $60 West Texas benchmark and $1.50 natural gas.

You have a range of producers in Canada who, although the share prices have doubled in the last year, are selling at half of net present value and selling at 1.5 to 2 times EBIT. This is really, really, really cheap. Are there risks? Absolutely. The idea that your own federal government is sabotaging you, something that Americans aren't unfamiliar with, is certainly a risk. And certainly, too, when you talk about oil and gas, you're talking about a very politically incorrect industry. You know, Greta Thunberg, the famous Swedish 15-year-old Nobel laureate, doesn't like oil and gas, as an example. But the truth is that it is an extremely efficient fuel and feed stock substance, and I suspect the peak oil demand will occur sometime around 2040.

So, if one can set the politics of oil and gas or... pardon me, the narrative of oil and gas aside, the financial opportunity that's offered up by the finest oil producers in the world, but particularly in Canada where they're unusually depressed, is attractive to me. Names that somebody should consider? These aren't investment recommendations, and I own them: ARC, which is what I consider to be the highest quality but probably not the cheapest of the Canadians... Tourmaline...

For those who have a bit more courage, Birchcliff, which is a pure play on natural gas, and Peyto, which I think has probably overcycled the lowest finding and development costs in Canada... are names which are attractive. For your listeners who have the courage to take a lot more political risk and deal with a lot more financial opacity, the Russian resource stocks are the cheapest resource stocks on the planet. And in oil and gas, that is true, too. So names there like LUKOIL and Gazprom, if somebody has the courage to deal with a truly capricious federal government, those are very cheap names.

Dan Ferris: Have they been perennially cheap or have there been opportunities to reap some good profits in them? I don't know much about them.

Rick Rule: They have been perennially cheap, and they have been perennially profitable. Now, your listeners need to understand that if something goes visibly wrong in Russia – which seems to happen three or four times a year – Russia delivers negative surprises on an amazingly consistent basis. These stocks are unusually impacted. They trade on sentiment and narrative as much as they trade on financials.

They are also cash machines. It's interesting to think that a tyranny like Russia is substantially a more efficient place to be a private operator because of lower taxation and the fact that the state relies on the oil and gas industry... Which means that the regulatory environment is much more accommodative often in communist countries [laughs] than it is in supposedly free countries.

Dan Ferris: It makes you wonder about the difference between, you know, "Is there a real environmental impact?" Because people worry about that with oil and gas. Makes me wonder what the environment looks like in various producing regions of Russia versus the United States or Canada or someplace.

Rick Rule: I would argue that over the last 30 years, both Russia and China have sacrificed the environment to their economic interests. I would also tell you, too, that as both of those societies get richer, their willingness to sacrifice their environment and their lifestyle to economics is declined precipitously. The shortcuts, as an example, that the major Russian nickel and platinum miner Norilsk took resulted in a truly ugly environmental scene in Russia, which Norilsk is required both to clean up and to pay a $2.8-billion fine as a consequence. A truly first-world response but a first-world response that didn't spend 10 years in litigation. Similarly, the same company, Norilsk, I think arguably took some operational safe cuts in their underground nickel mines, and, as a consequence, two of their shafts flooded.

I think what you're going to see in the next 10 years is a Norilsk that makes many fewer mistakes. So while what you say is absolutely true as an example, oil and gas transmission in Russia in the '90s was truly deplorable in terms of its environmental track record. As the Russian citizenry gets richer and the country feels its way through the social regulation of extractive industries, their performance gets better and better and better.

Dan Ferris: Interesting. Yeah. And not unexpected, I would say. All right. We've actually been talking for a while, and I'm really glad that we got the chance to do it. My final question, if you've listened to the show at all, is the same for every guest. I have to admit, knowing you as long as I have, I ask it with great relish because I know there's... And as I've tried to get across to the listener today, I know there's a lot more going up there than just, you know, what oil and gas and mining stocks to buy. So feel free to go as far and wide with this question, Rick, as you would like. And the question is, if you could leave our listener with a single thought today, what would it be?

Rick Rule: An unbridled commercial. Talk to me. I've enjoyed talking to Ferris listeners and Stansberry listeners for many, many years. And I like to give everybody an incentive to amuse me. Any of your listeners who would like to know the way that I think about the natural resource stocks which matter to them – which is to say, the ones they own – can access this. If you go to a website, sprottusa.com/rankings, and enter your natural resource holdings. Please no cannabis stocks. Please no technology stocks. Just stuff I understand. I will rank those stocks 1 to 10, 1 being best, 10 being worst.

And I'll comment on individual issues where I think my comments might have value. In addition, I'll send out two visual aids to anybody who mentions charts. One is a 50-year Barron's Gold Mining Index chart. I include that not because I'm a technical analyst but rather because it's the most inclusive and longest-running gold equities chart that I know, and it's a wonderful way to understand the anatomy of bull markets and bear markets and also a wonderful way to understand both the cyclicality and volatility of gold equities. The second chart is a 100-year commodity chart that talks about the valuation of commodities relative to other asset classes going back 100 years. So I would say talk to me.

Finally, Dan, I'll leave people with two thoughts. In terms of at least extractive industries and capital-intensive businesses, it is absolutely critical that your listeners become truly contrarian in resources. The stocks seem the cheapest when they're the most expensive, which is to say when commodities prices are high and PEs are low as a consequence of high E, they're actually expensive. When they seem cheap, they're expensive. When they seem expensive, they're cheap. In resources, you have to be a contrarian or you are going to be a victim.

You have to be in circumstances – you don't have to be, but it helps to be in circumstances where the commodity price is low enough that it's below the industry average cost of production. Because in that circumstance, either that commodity becomes unavailable or the price rises. So I would leave people with the sense that you need to be a value investor in resources. You need to be a contrarian or you will become a victim. And I will be happy to grade people's efforts thus far by looking at their own portfolio and commenting, where I'm able to, questions that your listeners and readers ask.

Dan Ferris: All right. Two great ideas instead of one. Thank you for that. And as always, a real pleasure to talk with you. And you gave us a lot of great ideas. I knew you would. You and I should talk soon again. [Laughs] It's been too long.

Rick Rule: Anytime now, Dan. We're almost neighbors. I'm in ensconced now in Anacortes, Washington. And I love the Northwest. And as I say, I've got a 30 to 35% pay raise in terms of my time, so I look forward to a discussion at any time that's convenient for you on any topic.

Dan Ferris: All right. Will do. Yeah. All right. Well, thanks again and I guess we'll invite you back soon.

Rick Rule: Thank you, sir.

Dan Ferris: I really love talking with Rick. I've known him for... oh, 22, 23 years. Something like that. He's taught me a lot about what goes on in the resource sector and, you know, who the best people are, who some of the worst people are, and everybody in between. He knows everybody in that business, and I've been very fortunate to know him and learn from him. And you can just listen.

I know you are probably – if you haven't heard Rick talk before, you're probably sitting here thinking, "Wow. That guy is brilliant." And you're absolutely right. And he's not just brilliant on investing. He's just an overall really, really plugged-in... his brain is turned on, you know, kind of a guy. Really great talk. Love talking with Rick. All right. Let's do the mailbag. [Music plays and stops] An unstoppable force is taking over our country's financial markets. And if you have any money in stocks right now, you could soon see the effects in your retirement account.

You see, stocks have soared over 70% since last year's crash. It's been one of the greatest rallies in American history. But according to my friend and colleague Doctor Steve Sjuggerud, a far more dramatic financial event is on the horizon. And it could blindside millions of Americans in 2021. Go online to www.2021bullmarket.com to hear exactly what he's predicting and what it means for your money in the coming months. That's 2021bullmarket.com. 2021bullmarket.com. Check it out. [Music plays and stops]

In the mailbag each week, you and I have an honest conversation about investing or whatever is on your mind. Just send your questions, comments, and politely worded criticisms to [email protected]. I read as many e-mails as time allows, and I respond to as many as possible. You can also give us a call at our new listener feedback line, 800-381-2357. That's 800-381-2357. Tell us what's on your mind. This week, I got two e-mails. They're really good ones. But [email protected]. Let me hear from you. Even if it's a criticism. OK? I can take it. Just, you know, be polite. I can take it.

All right. The first one is from Levi N. And Levi said, "Hello, Dan. Would love your thoughts on the following quote from Druckenmiller on CNBC this morning." And he included a video. But he's got this quote that he included in his e-mail. And he's talking about the 10-year interest rate. He said, "If it goes to 4.9%" – which is the congressional budget office normalized projection – "the interest expense alone will be close to 30% of GDP every year. That's basically what we just spent on the COVID emergency in the last year. There is no way we can afford to have 30% of all government outlays be toward interest expense."

Then he continues. He says, "So what will happen is that the Fed will have to monetize that. When they monetize it, I believe it'll have horrible implications for the dollar. I think it's more likely than not that within 15 years we lose reserve currency status." And that's the end of the quote that Levi N. included from Druckenmiller. Stanley Druckenmiller on CNBC recently.

And Levi N. says, then, "What do you think he means by, 'The Fed will have to monetize that? And when they do, it'll have horrible implications for the dollar?'" So I'm going to ignore some of your rest of your e-mail, Levi, and focus – because you ask me again late in the e-mail, "What does he mean by monetizing the dollar? How does that work and/or what does it look like? And what could that do to influence the U.S. losing reserve currency on the dollar?"

And then he finishes up. "Never miss an Investor Hour Friday Digest. Always enjoy your Extreme Value issues. Thanks for all you do. Levi N." Thank you, Levi. This is a good question because we throw the word "monetize" around, and we don't often see it defined. And it's really simple. Think of it this way. When the Federal Reserve engages in what it calls quantitative easing, it simply prints money and then goes into the bond market and buys bonds – mostly Treasury bonds.

And it buys them from the people who are already holding them. Right? It buys them from all of the – what do they call it – authorized dealers or something. They have an official term for all the people who deal in treasuries like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan and a bunch of others. I think there are about 20 of them now. And that's what happens. When you monetize the debt, it's different. Monetizing the debt means the government is printing – the government is issuing debt for the purpose of the Federal Reserve buying it. You see? So they're just – so that's what's happening now, really.

Because all of these many trillions of dollars more than we take in in taxes, several trillion dollars just in the past year – that money is new debt issued that the Federal Reserve buys and prints money to buy. That's what we mean by monetizing the debt. So imagine a situation where they're selling new debt and monetizing it so that they can pay the interest on existing debt. And then, you ask, "You know, how would this affect the value of the U.S. dollar? How would it affect, you know, the U.S. dollar losing reserve currency status?"

Well, it's pretty easy to see that if we're printing money as fast as we can just for the purpose of issuing new debt and paying off interest, the dollar kind of loses its credibility there. And Druckenmiller's suggesting over the next 15 years we – if we keep this up, it's more likely than not that we lose reserve currency status in the next 15 years. That's what he's talking about. But he's referring to it specifically relative to this issue of interest rates going up and too much of government outlays going toward interest expense. Hope that helps, Levi. Very good question. I'm glad you asked it. Our second and final question this week is from Al M. Al M. writes just about every week. He writes a lot.

And he tends to write, you know, long, thoughtful e-mails, and I don't include them because sometimes I feel like cutting them up in pieces kind of doesn't do him justice. But I'll include some of his latest one this week. And he just said, "Dan, I think your comments about Tesla were exact and right on." And I'll stop right away. I wrote about Tesla recently in the Stansberry Digest. I write the Friday Digest most weeks for Stansberry. And, you know, I just pointed out that – we discussed it on the program a while ago.

Their only source of consistent profit is these regulatory credits they get because they make zero-emission vehicles. So they get the regulatory credit. Then they sell it to another company that makes internal combustion vehicles so that that company can be in compliance with the emission regulations. You see how that works? Right? The EV company, Tesla – the electric-vehicle maker – earns the credit by making electric vehicles. And other companies need the credits, but they can't earn them because they make internal combustion vehicles.

So, they must buy them from Tesla. Well, I pointed out recently that one company called Stellantis – which is really a merger of Peugeot and Fiat Chrysler – was saying, "Hey. We don't need to buy this stuff anymore." And they were getting... It was a lot. It was like a couple-hundred-million bucks or something worth of these things from Tesla. It was a big chunk of the like $500 million or so – $530-odd million that Tesla did like last quarter, annualized that to $2 billion.

So, I think it came to around 10 or 11% annually. Put it that way. OK? So decent chunk of Tesla's regulatory credit income, which is all profit. Right? Because they don't need to spend anything extra. They're spending money to make cars. And then on top of that, they get this regulatory credit gravy. But the regulatory credit gravy wasn't there, so I criticized Tesla and I said, "This is not a business model that can be sustained." And Al is saying, "Yeah. You're right on." And he said, "Your ability to see through the nonsense is exceptional." Thank you, Al.

And he continues. He says, "First off, the climate change deal is nothing more than socialists wanting to tax corporations and figuring out a scheme to do so." Now, whether you believe they're socialists or not, I think he has a point. He continues, "Their mantra is controlled by the UN. They wouldn’t even consider Roy Spencer's write-up of studies he had done in consort with NASA where he had managed to get a spacecraft into orbit to measure infrared and other forms of energy emittance from and to the Earth."

In other words, the bureaucrats at the UN don't even want to hear scientific evidence. And he points out that he's a scientist – engineer, mathematician, worked at Dow Corning and IBM practicing science. And then, I just cut to the end. "Crazy as it all is, I think it rather amazing that value investing via your selections are doing very well. Well done. Al M." Thank you, Al. And I agree with the other things you were talking about, ESG investments being kind of questionable and Tesla and other companies sort of driving the narrative there.

And you mentioned Stephanie Kelton, who wrote a book about modern monetary theory. You know, she gives academic support for free money is what you called it. And I think that's about right. I think that a lot of really bad – or at least unquestionably untested – ideas, especially about things like economics, come out of academia and go straight into government. And for some reason, government thinks academia has instant credibility without, you know, actually knowing how to do something in practice. It's a lot of food for thought, Al. As you can tell.

You've given me a lot of food for thought, and I wanted to pass that on to our listeners. I thank you very much. Well, that's another mailbag, and that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. We provide a transcript for each and every episode of the Investor Hour. To get it, just go to investorhour.com, pick the episode you want, and scroll all the way down and click on the word "Transcripts." Sometimes it takes a week or two for it to show up. If you like this episode, send someone else a link so that we can continue to grow the show. If you know anybody who you think might enjoy it, just tell them to check it out on their podcast app or on investorhour.com.

Also, subscribe to the show on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, help us grow with a rate and a review. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Our handle is @InvestorHour. Follow us on Twitter at the handle @Investor_Hour. If you have a guest you'd like me to interview, drop me a note at [email protected] or call the listener feedback line 800-381-2357. That's 800-381-2357. Tell me what's on your mind. Till next week. I’m Dan Ferris. Thanks for listening.

Announcer: Thank you for listening to this episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to investorhour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail... [email protected]. This broadcast is for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.