Why Gold Could Fall Over The Next Few Months

In This Episode

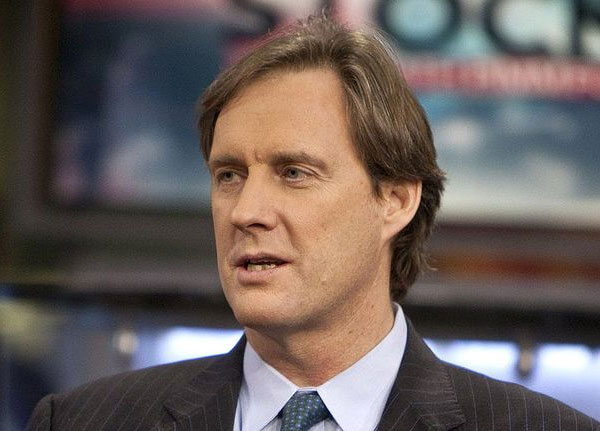

We guarantee you’ll learn plenty from this week’s guest, Mark Dow. Dan never fails to learn something valuable from reading Mark’s website and Twitter posts.

Mark runs Dow Global Advisors and the @BehavioralMacro twitter feed and blog, where he shares his trade ideas and risk management techniques, along with macro commentary. He has more than 20 years of experience as a policy maker, investor, and trader—all of which focused on global macro and emerging markets.

Not a lot of people can say they’ve worked as an economist for the IMF and at the Department of Treasury doing sovereign debt restructuring. Dow sheds light on what’s happening with the global economy today, and what he learned from helping emerging markets handle their massive levels of debt in the 1990s. And don’t miss his forecast for gold and precious metals over the next few months.

Featured Guests

Mark Dow

Dow Global Advisors

Mark Dow runs Dow Global Advisors and the @BehavioralMacro twitter feed and blog, where he shares his trade ideas and risk management techniques, along with macro commentary. He has more than 20 years of experience as a policy maker, investor, and trader--all of which focused on global macro and emerging markets. He's known for monetary policy and sovereign debt sustainability analysis.

Episode Extras

NOTES & LINKS

- To follow Dan’s most recent work at Extreme Value, click here.

- To follow Mark on Twitter, click here.

SHOW HIGHLIGHTS

6:02: Mark recounts his trips to examine sovereign debt structures in countries like Angola, Zimbabwe, and Equatorial New Guinea, and stumbling on one slush fund a President had stashed away.

6:58: Mark shares the story of a gun being pulled on him in Angola, and why building inflation indices can be so dangerous there.

9:56: Dan asks Mark about the repo market. “All of the sudden it’s making headlines because the interest rate went up 4x or 5x overnight.”

14:35: Most people think the Fed strives to keep rates low to stimulate economic activity – but Mark says that keeping rates low is actually central to its real agenda.

15:25: Mark goes over the three types of liquidity, from systemic liquidity to market-making liquidity to credit, or rollover, liquidity.

17:16: When it comes to markets, interest rates matter – but here’s why “risk appetite” matters a lot more.

24:42: The Obama administration expected the old normal of 3% economic growth to be reached again once the US emerged from the financial crisis – but Mark points to two changes, beyond policy or politics, that make those days long gone for America.

28:21: From trillions of dollars in government spending, to hundreds of billions of dollars in tax cuts, not to mention massive QE – here’s why all of these forces never seem to move the economic needle for Americans, according to Mark.

32:28: Dan asks Mark about his bearish forecast on gold, and Mark explains why he’s expecting a pullback in gold and precious metals.

49:39: Steve J. from the mailbag asks how to invest a retirement account like a Roth IRA differently from a standard retirement account.

Transcript

Announcer: Broadcasting from Baltimore, Maryland and all around the world, you’re listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour. Tune in each Thursday on iTunes for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive at investorhour.com. Here is your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast. I’m your host Dan Ferris. I’m also the editor of Extreme Value, a value investing service published by Stansberry Research. Great show today. We have another macro guy, Mark Dow, on the program. Can’t wait to talk to him. Can’t wait to learn from him. And we have some great feedback, very good questions about interest rates and stocks, gold, and WeWork, and just lots of good stuff.

Before we talk with Mark Dow, speaking of WeWork, just a couple thoughts. Last week what did I say? I said WeWork Securities are not appropriate for the portfolios of mammals, reptiles, marine animals, or birds. I said cockroaches could buy them because cockroaches can live a week if you cut their head off, and they can survive 30 minutes submerged underwater, and I figured, well, they can take the pain if anybody could, right?

That’s what I told our audience at the annual Stansberry conference in Vegas, and that’s what I told you on the podcast. I noted WeWork seven and seven-eighths bond prices. Those are the bonds due May 2025. The prices dropped to around $84, and then last Thursday they spiked up to around $90. Somebody got happy. And then earlier this week they crashed below $80.

Now, if you back up a little bit, October 2 Fitch Ratings, the credit ratings agency, cut WeWork’s credit rating to CCC+, and their definition of the CCC category is very simple. Default is a real possibility, period. Later on in their ratings document it says, “Substantial credit risk is present at CCC.” Not good. Very simple.

So, earlier this week when the bonds dipped below $80 and they were yielding 13% according to Bloomberg, the Financial Times said it was because JPMorgan Chase, you know, that company that failed to take WeWork public a few weeks ago, was putting together a bailout package that was turning out to be very expensive. One part of the $5 billion package was $2 billion in unsecured debt-bearing interest of 15%.

That’s like double the 2025 note coupon of seven and seven-eighths, and it’s like saying, “Wow, this thing is going wrong so fast. We need to get paid a whole lot up front before you guys disappear from existence.” At the same time, JPMorgan Chase is working on this big $5 billion bailout, WeWork’s largest shareholder SoftBank hired a Wall Street bankruptcy specialist, a firm called Houlihan Lokey to figure out ways to reduce WeWork’s liabilities.

They were also going to have a look at the accounting because by the accounting in the IPO filing, these guys are losing a ton of money. So, they want to make sure that they’re not losing even more I would suspect. I said in my WeWork rant a few episodes ago that I don’t think the company will survive, but I have to admit, things are going south much faster than I ever imagined if SoftBank is hiring a bankruptcy specialist already.

So, I must withdraw my earlier advice and I think even cockroaches should sell their WeWork bonds now. WeWork Securities then in my opinion are not suitable for any earthbound lifeforms. OK, that’s up to the minute WeWork.

One more thing before we get to our interview with Mark Dow. So far this year we’ve had straight up macro guys like Kevin

Muir and Collin Roach, and we’ve had other folks with macro insights like David Levine and Jesse Felder, and lots of other input about macro issues here and there from folks like James Grant for example.

One of the big macro concerns is politics, and I think we’ve learned a little something, and oddly enough just recently on Twitter in the last day or two Collin Roach summed it up really well. He said, “It’s better to think of the U.S. economy as doing well or doing poorly in any given time in spite of the government rather than because of it.” I don’t think that’s literally always true, but I do believe that’s far and away the most accurate model of reality.

So, stop selling things in other words. The advice that comes from that is stop selling things because the government says it’s going to do this or says it’s going to do that or even does something that sounds crazy even now and then. Another big macro concern that we’ve talked about throughout the year is the actions of the Federal Reserve. Again, I think the mistake is believing the Fed has much control over anything.

It’s a mistake to buy and sell based on what politicians say or what the Fed says. These are like knee-jerk overreactions that wind up losing you money and churning your account. Just a few observations. Obviously, I don’t know everything and these things are ongoing, so we’re going to learn some more today in fact, and let’s do that right now. Let’s talk to Mark Dow.

This week’s guest is Mark Dow. Mark Dow runs Dow Global Advisors and the behavioral macro Twitter feed and blog where he shares his trade ideas and risk management techniques along with macro commentary. He has more than 20 years of experience as a policymaker, investor, and trader, all of which focused on global macro and emerging markets. He’s known for monetary policy and sovereign debt sustainability analysis.

Dow has been a senior portfolio manager at Farrow Management LLC, a global macro hedge fund, a portfolio manager at MFS Investment Management, and a senior sovereign analyst at Putnam Investments. He began his career in Washington where he worked as an economist at the International Monetary Fund, the IMF, and at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. He specialized in debt sustainability analyses and sovereign debt restructuring. You don’t hear that every day.

He did his graduate work at the Fletcher School and got his undergraduate degree from UC Berkeley. He speaks five languages and resides in Laguna Beach. Mark Dow, welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour, sir.

Mark Dow: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Dan Ferris: Not a lot of folks can say they worked as an economist for the IMF and at the Department of Treasury doing sovereign debt restructurings. That must give you a view of the world that very few of us get to have.

Mark Dow: I was really, really lucky. A lot of good luck goes into one’s career. It’s not enough to work hard. You really have to be in the right place at the right time and I was. It was the early 90s and a lot of emerging markets were having trouble digesting a lot of the borrowings that they’d done in the 80s. Some of it was from markets but not so much.

Most of it was from other countries lending them money so they would turn around and buy their products and then the country would go belly-up and then we had to restructure them. Most of it happened at a place they called the Paris Club, and we would get together monthly and negotiate the debt of countries that had problems. Usually they were under an IMF program of some sort, and then we monitored the existing agreements to see if countries were keeping up with them.

Then at the IMF it was more the general economists who parachuted into countries once they caught fire and you try to diagnose on the fly what the problems were that got them into trouble and recommend a set of policies that you thought would help them get on the right path. Usually it was something like if you cut up your country’s living beyond their means, inappropriate policies that made things worse, and then the IMF would say, “OK, if you cut up your credit cards, we’ll give you a low interest rate bridge loan to help you get back on your feet. To get back on your feet you have to do X, Y, and Z.”

And then you kind of hope that the countries would take the medicine; sometimes they did, sometimes they didn’t. But you just get to see a lot of countries that way. It’s a little bit like being in the emergency room. The doctor in the emergency room sees so many patients that there’s a pattern of recognition to it. You start to recognize things early on, “Oh, I’ve seen this before” or “I’ve seen this element before. This is like that with this little difference.” You just build up a data set that helps you recognize things quickly.

Also, to be frank, it gives you a pretty good bullshit detector if I can say that as to what’s plausible and what isn’t because you’ve kind of been there on the inside and you’re not guessing.

Dan Ferris: Not guessing is a good thing. I wonder, could we get you to tell us a story like were you in Mexico? Automatically as soon as you say emerging markets and debt restructures, I automatically think of Latin America. Is that fair to say that you spent some time there?

Mark Dow: I did, but because of my language skills I probably spent more time in Africa because in Africa the colonial languages are English, French, Portuguese, and in a couple of places Spanish. So, I did more work there. I was involved in Mozambique’s exit restructuring. I was in Angola just after the war. I even went to places people couldn’t find on the map. I went to a place called Equatorial Guinea. I remember it was crazy.

It was just crazy, and I remember finding a bank account, kind of a slush fund that the president had in the Central Bank accounts and illegal payments were being made by oil companies. It became a bit of a political issue. Anyway, it’s really neat. You went into countries that had problems that were starting with fixed exchange rates, floating exchange rates, different kind of budgetary regimes, and you just started to learn what works, what doesn’t. You end up with a very pragmatic approach and sometimes eclectic.

Dan Ferris: Mark, do I watch too many movies or was your life ever in danger in any of these places?

Mark Dow: There was one time I had a gun pulled on me in Angola. I was going to the Central Bank on a Saturday morning because I had work to do. I had to help them build their inflation indexes. At that point in time in Angola, it was shortly after there had been a cease fire, if you went to a money changer basically to get dollars you would get stacks of kwanza. That was the name of the currency was the kwanza.

They would stack them up so if you gave them $100, they would give you five stacks. They didn’t even count the bills, right? That’s how bad inflation was. So, I was helping them build inflation indexes and such, and I was going from the hotel to the Central Bank. It wasn’t that far. Central Bank is beautiful. It had all the intricate Portuguese, azulejo but intricate tiling that Portugal is famous for because it was the Portuguese colony and it’s a super beautiful building.

But I was going there, it wasn’t that far, and someone in a police uniform waved my taxi over to the side of the road. He approached us and I showed him my United Nations passport, and he said, “You’re not allowed to have that and you’re not allowed to be riding in this car” and he was making up all kinds of reasons, and my Portuguese was good enough to have this conversation with him.

And then he went to get into the front seat of the car. He had his gun out, and then he opened the door and went to get in the front seat and I said, “I’m out.” I just got out. I took the risk and I crossed the street with my briefcase and got out of there, and that was it. He didn’t chase me, didn’t shoot at me. Nothing else happened.

I found out later that guys were renting police uniforms for the weekend to shake people down and get money from them. There was a foreigner who had recently been taken. The guy drove him off into the hills and they killed him. In retrospect, I didn’t realize how scary the moment was until later. That’s often the case. But the guy had a gun kind of pointed in my direction and then jumps in the car. I knew I just didn’t want to go somewhere with him, and it was still in the downtown area of _____. So, that was probably as sketchy as it got.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, I think one of those per lifetime is probably enough. One thing I’ve seen in your Twitter feed, and I hope you don’t mind I’m just going to bounce around on topics because I know that our listeners are kind of starved for information on this macro stuff. As you and I discussed on the phone previously, they just tend to read what’s in the headlines and what some guy on TV says and what some guy like me says. It’s better to hear it from a guy like you.

Recently something I’ve been trying to wrap my arms around that I don’t quite understand is this repo business, the repo market, which is something we never hear about, and yet all of a sudden it was making headlines because the interest rate went up about 4x or 5x overnight. I’m really praying that you can shed some light on this for me, because I’m in the dark still.

Mark Dow: It’s a complex issue, but I think a lot of people have fundamental misunderstandings about how a central bank works. There’s two kinds of money, right? One kind of money is what the Central Bank creates, and that’s the federal fund system. It’s a closed system, so that money can’t leave that system. That money is there primarily so that banks can settle with each other. They can settle payments easily, right?

That’s really it. People have this idea that the Central Bank creates money and then banks lend it out. It doesn’t work that way because you and I can create money, right? You can promise to give me a service and I can say I promise to pay you for it $100. You give me the service and I give you a check for $100. That’s credit. You’ve extended me credit. No central bank was involved, no regulatory body, and I purchase goods, your services, with that credit.

Now, if my credit worthiness is sufficiently good, you can turn around and sell that to somebody else and say, “Listen, Mark Dow owes me $100. I’ll sell it to you for $99.73 because his credit is good and my credit is not so good and they’ll sell it to me for less.” And my credibility is perceived, you’ll sell it for $100 and the person will take it. That means we’ve created money, right? All of a sudden, we have a medium of exchange.

Again, no central bank involved. People have this misconception that the Central Bank creates money and that money gets leant out; it doesn’t. That money is used really for an internal settlement system and to provide sufficient currency to lubricate transactions in the system. That’s what they do. These reserves, they’re called reserves, are highly liquid for settlement purposes, and the banks need to keep a certain amount of reserves on hand so that they can meet their short-term liabilities.

If they have insufficient reserves then they have to go borrow them from somebody else. The requirements for reserves went up significantly after the crisis, so banks now have to hold more because we all want a bigger liquidity cushion. For a long time it wasn’t an issue because the Central Bank did what they call QE, and what they were doing there was they were buying a lot of bonds and injecting this money into the federal funds system, so the money wasn’t going to be leant out, but the banks had a lot of liquidity with which to settle.

The idea was that the Central Bank bought enough long-term bonds, it might drive the interest rate down, and that would encourage at some point a resumption of lending activity, and at a minimum it would help people refinance and fix their damaged balance sheets from the crisis. That’s how it’s supposed to work. Of course, there was a psychological effect that if the Fed is intervening, they’re helping us. The Fed has got our back and things will get better.

That psychological effect ended up being much more powerful than that interest rate effect. So, what the Fed is doing now is very different. They’re not trying to drive long-term interest rates down. These banks have to hold a lot more reserves these days for regulatory reasons, and all of a sudden, we had that _____ for a long time from the QE operation and we sort of drained this from the system.

At some point there was an inflection and they said, “OK, now we don’t have quite enough to meet our reserve requirements and to satisfy all the settlement needs that we have.” That kind of happened in a spike. You didn’t know when that friction point was going to come and it came, and it came because the regulatory requirements were higher, but also, there were a lot of corporate tax payments that had to be made.

So, the settlements increased. All of a sudden, the interest rates spiked. People needed reserves and they were willing to borrow them at a higher rate. So, the Fed was intervening here and is intervening to keep the interest rate at the policy level. So, they’re not trying to drive interest rates lower to stimulate economic activity. They’re just trying to execute their policy efficiently.

So, essentially what’s happening is the reserve requirements have increased significantly since the crisis, so the economy is probably increased in size by 50 or 60%. Nominal GDP has increased by 50-60%. It’s been 12 years or so, and the combination of the two meant that we got to a point where there was a shortage of reserves for liquidity purposes.

On my blog, Behavioral Macro, and this one is open to the public, there’s an article called “Misunderstanding Liquidity.” People use that term a lot, they say liquidity, but there’s three types of liquidity and people don’t make the distinction. It’s a great red flag for filtering people out who don’t know what they’re talking about if they don’t draw the distinction.

The first kind of liquidity is what I call "Systematic Liquidity," and that’s what we’ve been talking about here. It’s so that the banks can clear, the banks can settle with each other seamlessly, and the Fed supplies reserves and takes reserves out of that system so that can happen. The second kind of liquidity is what I call "Market Making Liquidity," and that’s when you call up Goldman Sachs on the phone and you say, “Listen, I want to buy some Argentine bonds. Where’s your offer? Where’s your bid?”

The degree to which they want to provide liquidity for that transaction is a function of their risk appetite and has nothing to do with what the Fed is doing, right? They just say, “I want to take more risk, I want to take less risk” and they’ll quote the bid and the ask tighter or wider depending on that risk appetite. When we talk about liquidity in the market, that’s the liquidity that we’re talking about. Can you transact at a low cost? Are people willing to buy and sell?

The third kind of liquidity is what I call "Credit or Rollover Liquidity," and that has to do with risk appetite as well and really has nothing to do with the Fed. It’s when a corporate bond matures; can they roll it over? Can they issue a new bond? Or a company who wants to raise money on the capital markets, can they issue a bond? It has a little bit to do with Fed policy to the extent that it’s interest rate sensitive, but it’s usually not. It’s usually much more about risk appetite.

As we saw, people have this tendency to think that risk appetite is linked to the price of money much more than it is. Sure, the price of money matters, but if it were the driving factor, we wouldn’t have had people falling all over themselves to borrow from 2005 to 2007 when the federal funds rate was at 5.25. And then when the federal funds rate was zero between 2010 and 2012, nobody borrowing at all. So, interest rate matters, but risk appetite matters a lot more, and that’s usually a function of do you feel secure in your financial situation, in your job, what have you, your business, and do you see other people around you making money?

That tends to trigger. This is why the dotcom bubble happened when the policy rates were at 7%, right? It wasn’t about cheap money. It was about people getting greedy. So, these three types of liquidity: systemic, transactional, and credit or rollover liquidity, it’s important to distinguish amongst so that we know what we’re talking about.

Dan Ferris: Wow. I’ve seen that article on your website, and I encourage people to go check it out, and I thank you for kind of summing up because that’s exactly why we invite guys like you, and I appreciate it. So, in other words, this thing that made headlines was not a huge disaster. It was just kind of a blip in the system. Is that what you’re telling me?

Mark Dow: Yeah. It was really about the systemic liquidity and people were mistaking it for credit liquidity, that it was a risk appetite problem, that it was a harbinger of bad things to come. So, because we have the memory still in the back of our minds, the "disaster myopia" as psychologists call it of the crisis. The day after you’ve been mugged, you’re going to assign a higher probability to getting mugged again than is probably likely, than is probably the case.

Had it not been for the government stepping in, we were eight hours away from standing in front of ATM machines in our pajamas hoping there was money still in there. And I was there inside the system, right? I was working at the hedge fund at that time, and I saw that Goldman Sachs wasn’t trusting Deutsche Bank. They weren’t clearing with each other. They had to clear through the Fed because the banks had stopped trusting each other, and that’s a sign that it’s about to end.

Fortunately, the Fed came in and kind of liquified things and they set up all those acronym markets that they set up to get the commercial paper market to start working again, all the different credit secured markets to start working again. Had they not done that, we would’ve been in big trouble. Anyway, the point is, that memory made people go to the worst possible place immediately when they saw the hiccup in the repo market, and most people don’t understand enough about the distinction between the Fed funds market and the overall money supply to see that.

If you step back for a second and look at the people who are insisting this is QE and this is a crisis, they’re typically the people that have been predicting crisis for quite some time, and they just keep being wrong. They keep saying it’s going to blow up, it’s a bubble, they’re going to debase the currency, we’re going to have hyperinflation, Fed is making a policy error, and these things never happen.

So, it’s almost as if they’re still trying to find a way to claim victory somehow that you know "You see? I told you this was going to happen," and they’re reading the worst possible thing into it, and some of them have business models, frankly, that are built on this, this zero hedgeification of things. They have to sell gloom and doom because they know fear sells better than nuanced not dramatic analysis.

So, that’s really it. We are at a point where the Fed has to restructure some of its plumbing because the world has changed significantly from the GFC, so there will be hiccups here and there, but it’s not indicative of a lack of risk appetite or credit problems. If there were credit problems, we would see that in the spreads in credit markets, and those aren’t there.

Dan Ferris: I see. So, the repo thing was a minor systemic liquidity problem having nothing to do with what you’re calling market making liquidity or credit liquidity. Do you see any problems?

Mark Dow: Or the global economy or anything.

Dan Ferris: OK. Anything at all.

Mark Dow: Nothing to do with the real economy. It was really just the bank’s settlement system. They ran short in reserves in part because they’re required to hold a lot more of them, that’s all. We knew there was going to be some point where that was going to happen because the economy grows and the demand for reserves grows over time, and they had reduced a little bit the size of the balance sheet.

So, we just didn’t know when that was going to happen and it just happened. It’s probably going to happen again at year end. The Fed is going to be ready for it now. At the end of the year, a lot of banks try to shrink their balance sheet dramatically for window dressing purposes, and that puts a lot of demand on reserves, so we might see that again. I doubt it’s going to be anything like what we saw this last time, but we have these scares all the time, to be honest.

If you think about it, remember last year everyone said QT, QT, they’re shrinking the balance sheet, quantitative tightening, they’re reducing reserves in the system, and it’s hitting the stock market because the stock market happened to be going down at that point in time. Well, if the size of the Fed balance sheet was driving the stock market, and a lot of people have been arguing over the past 10 years.

It’s an artificial rally. It’s being propped up by the Fed balance sheet. I’m sure you’ve seen on Twitter all the charts purporting there’s a correlation between the size of the Fed balance sheet and the S&P 500. If there was really a causal relationship, we shrank the balance sheet and stock market went down temporarily for other reasons and people mis-ascribed it to that. Well, the stock market came back and the balance sheet didn’t.

Only now are they starting to grow the balance sheet again, but between there and now the stock market is up 20% so far this year, right? So, that would not have happened if the size of the Fed balance sheet were really driving the stock market. There’s just no linkage. There’s no direct linkage and indirect linkage is very, very weak.

Dan Ferris: So, what do you think the real cause of the 19 almost 20%route in late 2018 was?

Mark Dow: Well, we had a big selloff in December for a lot of reasons. We were kind of ripe for it. The market was weak technically, and a few things scared people, frankly. A lot of people didn’t understand QT and they were afraid. They thought it was going to drive the market lower. And then the Fed communications at the beginning wasn’t – Jerome Powell said things that Janet Yellen had said, but there wasn’t a reaction to it. When he said it, it didn’t sit well with people and people got afraid.

We also had a downturn in economic activity that resulted from – remember we had a big crash in oil prices. It was the second crash we had in oil prices, right? That tends to drag down economic activity. Also, the fiscal stimulus was rolling off. Remember, under the Obama administration he inherited a big recession and they had to dig themselves out of a hole, but one of the problems that people didn’t notice, they expected us to return to the 3% growth that we had become accustomed to over the past 30 years, but our demography had changed significantly, and so had the credit market in the following way.

The Baby Boomers entered their peak years in the 80s and 90s. Those are the peak years. We also had women entering the workforce in a secular way, women that had been staying home before and were now coming into the labor force. So, we all know that the growth equation is a function of the growth in the labor force, the effective labor force, and whatever productivity gains you could squeeze out of technology.

Well, the labor force size was growing significantly because Baby Boomers were entering prime years, and women were coming into the workforce, so that gave us a higher rate. The other thing is coming out of the 80s if you remember back in the 80s, we had really, really high interest rates because we had inflation, right? Jimmy Carter picked Paul Volcker, Paul Volcker said, “Screw it, I’m going to clamp down on this economy and squeeze inflation out” and that started a disinflationary process.

I remember my parents; people didn’t get mortgages back then because the interest rates were 13 and 15%. That was the period that they lived in. As that came down, all of a sudden financial operations became feasible for people. You could get credit cards and they wouldn’t kill you. So, the Baby Boomers were entering the prime years, women were coming into the workforce, inflation was coming down, and deregulation was hitting the financial system. All of these things led to a big credit tailwind.

We had the demographic factor in our favor, but we also had a huge credit tailwind where all of us could get credit cards. All of a sudden, we could buy things on credit when we weren’t able to before. That kind of came to an end, and that lasted for a long time and then it went to the mortgage market and all kinds of other technologies that made it easier for us to take on credit, to carry more credit.

That all ended with the global financial crisis and now I know corporations have borrowed more and governments have borrowed since the crisis, but households and the financial sector have borrowed a lot less. However you cut it, we don’t have the tailwind of credit deepening that we had for 30 years. Our demographics are less favorable. The millennials might change that because they’re entering the labor force in size and that’s helpful, and that phenomena is just starting now, but the demographics haven’t been good and the credit tailwind is now a headwind because we’re just not going to borrow nearly as much.

So, the natural growth rate of 3%is really more like 2%. What happened? That’s basically the growth rate we got over the Obama presidency. Trump came into power and initially a lot of people who had been fighting the Obama recovery for political reasons, they said, “OK, I’m optimistic we’re going to get tax cuts and we’re going to grow” and that led to a little bit of growth, and then we got a very large spending package and on top of that a very large debt cut package.

So, that was a huge fiscal stimulus that lasted about a year and a half, and you saw the bump in growth. You can look at the GDP charts and you can see we had a bump in growth. Well, we started coming off of that late last year. So, we had people afraid of QT, we had the oil, the crash in the oil price having a large effect, and we had the fiscal stimulus, the spending rolling off. And of course, the tax cuts didn’t work the way they had planned or promised.

It didn’t stimulate investment as people said it would. In fact, tax cuts didn’t under George Bush either. You need certain conditions to obtain for tax cuts to translate into investment, and these were not those conditions. So, that’s why we had this slowdown and the stock market did really poorly which set us up for the stock market recovering this year. That’s why we’re up 20%.

Dan Ferris: So, there are a lot of questions I want to ask in there, but I’ll go with the last one. What are the conditions under which tax cuts would have a more stimulative effect?

Mark Dow: Typically when supply is the problem. It’s famously a supply side policy, right? The idea is, well, people would be building, people would be starting new businesses if not for the cost of capital or high taxes or whatever the issue happens to be. Well, our problem, if we really had a problem where supply was constrained, that means demand is exceeding supply and supply is not meeting it, we would’ve had inflation.

If you have excess demand relative to supply, you have inflation, and we haven’t had inflation, so those conditions don’t obtain. But in those conditions when there are inflationary pressures because the supply side is bottlenecked, and you could argue that at the beginning of the 80s, we had some of that. I think the bigger push to growth was the decline in the interest rates and the decline in inflation, but we certainly had supply bottlenecks at the beginning of the 80s and the marginal tax rates were much, much higher.

So, under Reagan if the top marginal tax rate goes from 70 to 35 or 39 or whatever it happened to be, that’s a much bigger thing than the top rate going from 39 to 35. That just doesn’t get people out of bed in the morning. So, the combination of the level from which the tax cuts were happening and the supply conditions not being a constraint led to people not responding with investment.

We saw this under George Bush. He tried two rounds of tax cuts, and we saw that to some degree under Obama because to get his fiscal stimulus package passed, he had to agree to more tax cuts than he would’ve liked to try and get some republican support. But we know that the only way, particularly in a crisis, the only way to get money into the system is for it to be spent. If you give a guy money and he’s afraid, his risk appetite is low, he’s just going to save it. He’s not going to use it.

That’s why tax cuts, you have to cut tax cuts into an environment where people want to take risks but can’t, and those are very specific conditions. The problem politically is that, I joke that an old wealthy guy will believe any economic theory you tell him as long as it ends up in a tax cut. It’s a little bit like saying if you eat ice cream every day, but you have to eat it every day, you’ll lose weight.

Everyone wants to believe that tax cuts will stimulate, so there’s a bias. I usually start my analysis by saying what are we biased to believe? And then you’ve got to adjust for that. OK, I want to believe this, so probably have to be careful about confirmation bias.

So, in this particular case, we all want to believe, no one likes to pay taxes, that tax cuts are going to have positive effects, that they’ll pay for themselves, and they’ll lead to a lot of investment or whatever people are claiming, but the empirical evidence suggests that the conditions for that working are very, very specific and very narrow, and they certainly haven’t been the case over the past 15 years.

Dan Ferris: Now, Mark, in the interest of time I hope you don’t mind, but I’m going to jump around a little bit here. A lot of our listeners, a lot of them, and me too, are wondering what a guy like you thinks of gold right now. I did see maybe on your Twitter feed you’re kind of expecting a correction in gold, are you not, in the gold price?

Mark Dow: Well, let me say two things. One is I’m structurally bearish gold in the long term. That’s different from how I trade it. One is a slow twitch phenomenon, and the other is just trading, whether you’re overbought, oversold, and what the patterns are telling us about expectations. So, lately I have been expecting a pullback in gold and precious metals and gold miners because people have been really bullish.

We had a big breakout in June, and I haven’t heard anyone say anything bearish about gold on TV. I watch CNBC a lot to hear what other people are saying, and some of the guys have been coming on for years, so you can kind of recognize whether they’re structurally bullish or bearish and what their biases are, and you can judge what sentiment. It helps me discern what’s in the price, what people believe the narrative is, and it’s up to me to decide whether it’s gone too far, whether I agree, whether I disagree, and people lately have been very bullish gold, so I’ve been expecting some kind of correction.

I don’t know how far it goes. At the end of the day it’s a function of interest rates. What kind of changed in this market for me and got me tactically bearish gold was not just that people had gotten very optimistic, but it was also that the ECB changed its monetary policy. It’s a bit complicated, but they tiered the remuneration of the reserves. They’ve had negative interest rates, so if you had excess reserves at the Central Bank you had to pay the Central Bank money to deposit with them, which is kind of crazy, right?

But that’s what they’ve been doing. So, they exempted a certain amount of excess reserves over a certain level from that negative interest rate, and ever since then the Boons, which is the benchmark for European yields, those bonds have started to sell off and yields have started going higher. So, the euro started to behave a little bit differently, and it’s had an effect on yields in the United States too, and as we’ve seen bonds have been selling off here and that has kind of continued.

We had a big run in bonds and I think people recognized that there was a safe asset shortage and they kind of overdid it, and once the buying got going, what they call the convexity buyers, the people who have to hedge their mortgage portfolio, were forced to buy more and more and it kind of feeds on itself. Nothing brings out the buyers like higher prices, right? You’re afraid it’s getting away from you and you have to jump in.

So, I think those factors, the kind of unwinding has given us a good environment for gold selling off. It really comes down if you want to track one thing for the trading oscillations in gold, I track the real five-year yield in the U.S. I look at the yield on the tips bond without the inflation adjustment, and typically if that’s going up or down, that will tell you what gold is doing. Obviously lower rates favor gold and higher rates hurt gold.

The big rally in gold since June came when people were talking about negative rates. Is the U.S. going to use negative rates? Are rates in the U.S. going to go to zero again? All those kinds of things. So, that’s it. The longer-term case against gold is simply that fiat currency innovated gold, kind of disrupted gold, and now electronic payments are disrupting fiat to some degree, not including Bitcoin in this. I think Bitcoin is a separate thing.

So, gold is just a lot less useful, right? Nixon closed the gold window back in 1971 and it stopped being a monetary asset, but the tradition of holding gold as a monetary asset is 5,000 years old, right? People say, “It’s not going to change. It’s 5,000 years.” Well, yeah, we rode horses for 5,000 years before we discovered the car. Things change.

The utility of gold is declining, and people are slowly coming around to that. It’s also not a very good hedge. We saw in the financial crisis, look at the gold price in 2008, right? We had a systemic meltdown. We were really, really close to the full collapse of the system, and gold went down in price, didn’t go up. It’s a questionable inflation hedge over time.

Indexed equities are a better inflation hedge over time than gold. Yes, you can cherry pick a chart that makes it look like gold does better as a hedge, but it’s really not, and it’s fading. With every passing day more people realize that it’s just not a very good hedge. It’s expensive. You have to pay storage costs, and it’s just not very good.

So, I think over time, people will continue to learn this and the younger generations won’t reach instinctively for gold whenever they get nervous about things. I think you have to be over 50 years old to think that way. So, the short-term and the long-term view for me often what I’m trading and what I’m thinking structurally are very different, or can be very different.

Dan Ferris: I see. You mentioned negative rates. I can’t help asking a macro guy what that situation looks like. Some people say it looks like they turned sovereign debt which is supposed to be this safe thing into toxic waste or at least a speculative instrument. What do you think?

Mark Dow: I don’t think it’s speculative at all. I think actually the only function, when the yield is negative on a bond, on a high-quality government bond, the only reason you’re buying it is for security. That’s the only reason you’re buying it. You’re certainly not buying it for the yield or the return, right?

Let me give you a very concrete example that I know personally to underscore this. My wife is from Italy. She grew up in Italy. In 2012, it wasn’t clear whether or not Mario Draghi was going to be able to do whatever it took. He kind of had to trick the Germans into protecting Germany because the Germans are very hard core about their monetary policy and the legacy of the Weimar Republic and hyperinflation. This kind of remained impressed in their memories for longer than you’d think.

They were talking about letting Greece go from the system and it just wasn’t clear if that happened if other countries would fall, dominos would fall. So, my mother-in-law, she wanted to protect her money. She was afraid that deposits in Italian banks could get confiscated if Italy left the single currency, left the euro, and that’s typically what happens. They freeze the deposits and they redenominate them, so you end up instead of having deposit from euros you get deposits in lira, but the lira declines 40% from the value that it had the day before.

So, I told her, I said, “You know what to buy, right?” And she goes, “What?” I said, “Buy the shots. Shots are two-year German bonds.” I said, “Because they can’t freeze those. You own those. It’s not a deposit.” And whatever currency Germany ends up with, if they leave and return to the deutschemark or Italy leaves and returns to the lira, the German currency is going to be worth more than the Italian currency, so just buy that.

Now, at the time she went to buy it, and she called me and she goes, “But the yield is zero.” I said, “Well, yeah.” And she said, “And the coupon is zero.” I said, “Yeah, but think about it. You have an option. You’re essentially buying an option on a 40% depreciation of your currency. If you hold that bond and either Germany leaves or Italy leaves, that instrument is going to make 40% for you once you translate it back into your home currency.”

So, that’s a very simple example of someone who would buy a zero, and same thing would apply to a bond with a negative yield. You’re buying that to protect yourself, not because you think you’re going to make money directly. And a lot of banks in Europe are forced to hold for regulatory purposes a certain amount of risk-free capital so they’re paying a tax in a certain sense to meet their regulatory requirements.

So, it’s kind of a counterintuitive thing for a lot of people, but it’s not a sign – it’s a sign that security matters more than anything. Security and meeting regulatory requirements are what matter most. It’s not a sign of impending doom or anything like that. I don’t think the U.S. would ever use negative policy rates here.

We could have negative yields in certain circumstances, but negative policy rates I don’t think so because of what that would do to the money market. Europeans don’t have the same kind of money markets that we do. You know the whole thing about busting the buck. The way our financial plumbing works, I think a negative policy rate would be very problematic, so I don’t think they would ever do that is my bias at least.

Dan Ferris: So, that’s as good an explanation of the negative rate situation as I’ve heard yet. It’s at least ironic though, isn’t it, Mark, that people are holding something for security that’s kind of guaranteed to lose them a little and they hold it to maturity?

Mark Dow: It’s like an insurance policy. You pay for an insurance policy in case your house burns down. You’re not going to make money on it, but you’re protected in that scenario. Apart from the regulatory reasons for holding these risk-free bonds or high-quality bonds, there can be this security reason almost like an insurance policy.

Dan Ferris: Forgive me for being dense, but what are they all so terrified of that they’re willing to hold all this negative yielding debt?

Mark Dow: A lot of times they just want to make sure that they get their capital back. In this particular instance, there’s not as much fear as there was in 2012, but a lot of people, they have to hold it because they run mutual funds and the banks are driving the rates lower because they have to hold regulatory capital. I think the regulatory factor means more now than the security, but I was more underscoring the security notion to make the point that at certain points in time, there are reasons to hold negative yielding assets that aren’t intuitively clear.

But you’re right that right now the security issues aren’t nearly as high as they were back in 2012. Also, what tends to happen in some of these cases, in the recent one, there was a lot of momentum buyers who bought hoping to sell at a higher price. That always happens whenever you get a trend in any asset.

Dan Ferris: Sure. I’m sure there are European bond fund managers who are having a career-making year, right? That’s what you’re talking about?

Mark Dow: Well, they were. It’s turned a little bit against them recently, that’s for sure.

Dan Ferris: All right, Mark. We are pretty much out of time here, but before I let you go, you’re such a sophisticated thinker. It sounds like you do some really sophisticated trades, and we didn’t talk at all about where you think the U.S. stock market is headed, the standard question. If you want to answer that, by all means go ahead. If I could just ask you to leave our listener with any thought at all, doesn’t have to be about the stock market or anything, what maybe a little bit more than a sound bite would you care to leave them with?

Mark Dow: What I try and focus on in behavioral macro, on the Twitter feed, is really about risk management. When I came to the money management industry, I saw a lot of guys who didn’t know anything. It was manifest. They knew nothing about economics, but they could make money, and I had to ask myself how they did that. So, I started looking at chart patterns and technical analysis. That’s how I got into behavioral finance, and I realized it really comes down to risk management.

A guy with very little knowledge can make money in the market if he or she knows how to manage risk well. If you have really good ideas and you’re really super smart, but you don’t have risk management, it’s harder. It’s harder to make money than the person who knows very little but has good risk management. I always say risk management uberalis. That’s really what matters. You’re always trying to set up asymmetric payoffs, and don’t try to think you’re smarter than anybody. Don’t bet the farm.

If you happen to have an edge that increases your batting average, that’s great, but there are two components to getting paid off. One is the asymmetry, risking one to make three, risking one to make five, whatever, and you need to do that. That’s your risk management. And the other is the hit rate of your ideas. If you get your hit rate up to 60%, you’re a hero, but you really make your money in the risk management and setting up asymmetric payoffs. I do a lot of inference from chart patterns and price correlations to figure out what’s in the market and whether or not people are too skewed one way or the other, and that helps me set up the asymmetric payoffs.

So, really, it’s not sexy to go to the party with the pocket protector and say, “I’m a good risk manager.” It’s much sexier to go in and say, “I’m master of the universe and I know where the euro is going to go.” But the one that makes you money is the pocket protector.

Dan Ferris: That’s an excellent message. Risk management uberalis, I love that and thank you for it, Mark. I certainly hope that you will come back and join us another time in the future. I personally have gotten a lot out of this and I’m sure our listeners have too. We’d like to see you back someday.

Mark Dow: I’d be happy to come back.

Dan Ferris: Great. Thanks very much, Mark. Bye-bye.

Mark Dow: Bye-bye, guys.

Dan Ferris: Hey guys, real quick, I just want to tell you something. As host of the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast, I also enjoy listening to other podcasts. It helps me figure out ways to make the Stansberry Investor Hour a better experience for you.

One podcast I really like is called We Study Billionaires hosted by Preston Pysh and Stig Broderson of TheInvestorsPodcast.com. It’s the biggest investor podcast on the planet, enjoyed by thousands of listeners every week. Preston and Stig interview legendary billionaires like Ken Fisher, the billionaire you’ve seen on TV; Jack Dorsey, founder and CEO of Twitter and payments company Square; and billionaire investor Howard Marks whose book The Most Important Thing I’ve recommended dozens of times.

Sometimes Preston and Stig spend a whole episode reviewing lessons learned from billionaires they’ve studied like Dell computer founder Michael Dell, tech industry maverick Peter Thiel, and macro trader Stanley Druckenmiller. Before starting the We Study Billionaires podcast, Preston went to West Point and Johns Hopkins, founded an investment company, and his finance videos have been viewed by millions.

Stig went to Harvard and worked for a leading European energy trading firm. They’re smart, experienced investors who know the wealth building secrets of billionaires better than anyone, and their listeners love it, and I’m one of those listeners. Head over to TheInvestorsPodcast.com and check out We Study Billionaires with Preston Pysh and Stig Broderson. The InvestorsPodcast.com; check it out.

OK, the mailbag is where you and I get to have a real nice conversation each week. I really enjoy it. I read everything you send me, even the Russian spam which I know you’re not sending me. The Russians are sending me that. So, just write in with all of your comments and questions and politely-worded criticisms to [email protected].

This week I’m going to pull things out. If somebody writes a long e-mail and there’s just one really good question, I’m just going to pull that question out, so don’t be offended if I didn’t read your entire e-mail. First one is from Steve J., and Steve J. asks, “How would you invest a retirement account such as a Roth IRA differently than a standard taxable account?”

Steve J., I don’t know that I necessarily would. I think some people are really active in their taxable accounts, and I think they maybe try to be less active in their retirement accounts, and they try to manage things that way. I do actually sort of do that, but it’s only because I have this old 401k. It’s this tiny little thing. I left the company a long time ago, and there’s very little money in there.

I’ve managed it OK, but I tend to be more active in my taxable account. Every now and then there’s some activity in the retirement account too. So, it’s not a black-and-white situation, but I suppose in general retirement is less active, taxable more active. That’s what I personally have done just thinking about it right now. Not saying that’s what you should do.

Hope that helps at all. OK, next one is from Tim D. and Tim D. says, “Dan, I can’t understand why you don’t feel low interest rates will propel stocks higher. The fundamental value of the stock is determined by discounting expected future earnings. The lower the discount rate, the higher the present value. Seems simple.

Given our weakening economy and compliant Fed, it’s likely rates will continue to fall. Where would you rather invest, in a money market fund yielding 1.7% or in a quality stock with a dividend yield twice that amount? Unless a whacko democrat is elected president, stocks are going higher. Tim D.”

Well, when interest rates are this low, Tim, I don’t think the prevailing interest rate is necessarily the appropriate discount rate. I think the discount rate is different for every business, and it’s more based on the type of business and the specific company than it is on some prevailing risk-free interest rate, so there’s that. That’s one thing. I would decouple those ideas that you seem to have coupled together.

Also, you probably have seen, I mean we’ve published them on Stansberry, there are times when the Fed is easing and lowering rates and the market is just kind of going down. The Fed will tend to do that, and sometimes they tend to anticipate it. They start easing as the economy starts weakening and then the market weakens. So, I don’t think it’s a no-brainer by any means that lower interest rates mean higher stock prices at all, and I would discourage anyone from investing on that basis unless you’re Mark Dow our guest today, unless you are a macro virtuoso.

I would just discourage you from assuming these relationships exist and focus more on the quality of the business that you’re buying. With that said, you said where would you rather invest, money market fund yielding 1.7% or in a quality stock with a dividend yield twice that amount? Again, it depends on the stock, it really does. It depends on the individual situation, but you make a good point there. I won’t say that you don’t.

Steve T. writes in, he says, “Hi, Dan. I recently started listening to your podcast. In your last one on October 10, 2019 I heard your diversity strategy recommendation of cash gold value.” That is what I’ve been doing and that is what I’ve been talking about since about 2017. So far, it’s worked out OK.

“Physical positions are hard to trade, so what is the best way to take positions in gold?” And then he says, “The GLD or the GLDM” which I think is a tenth of the GLD, “both are up significantly in the past month. Thanks, Steve T.”

So, up significantly in the past month is relatively meaningless and may mean that we’re ripe for a correction as our guest on today’s program indicated. As far as this idea of trading gold, to me it’s not a trade. To me, it’s a hedge against financial chaos. Our guest today made an interesting point that when there was real financial chaos in 2008, gold sold off too. People wanted dollars.

They were basically selling absolutely anything they could, so they sold their gold in exchange for dollars too because they were really scared. I think over the long term though it just makes too much sense to hold some gold. It’s been around for 5,000 years; I think it’s likely to be around for another 5,000. That’s my personal view on it.

So, I wouldn’t say trade gold. It’s kind of a buy and hold for a hedge against extreme monetary situation. It goes in cycles too, right? The cycle kind of bottomed out. Peaked in 2011, bottomed out late 2015, early 2016, and I think we’re still closer to the bottom than a new top. Although in the short term I agree, a correction. Looks like we’re kind of ripe for a short-term correction. I hope that’s helpful, Steve. Thank you for the question.

OK, one more, Nick J. says, “Dan, I absolutely love the show and have been listening for years and will be for years to come. The WeWork rant is so satisfying. If you look into SoftBank, specifically Mr. Son”, that’s Masayoshi Son, the chairman and founder of SoftBank, “you will see the entire goal of the fund is to pour capital into businesses they have invested in because of some ridiculous founder’s happy words and vision, and are now just continuing to add capital in inexplicable amounts so they can essentially have 2 or 3 times competitors and outbuy and outspend to give the competitive advantage.”

I think he means two or three times the capital that competitors have on hand so they can outbuy and outspend their competitors. And then he continues here, “NPR”, that’s National Public Radio, “did a special on this maniac Son and how he is an excessive gambler with a disorder.” Maybe like an emotional disorder of some kind. “Please check it out. It is called episode 943 ‘Unicorn Cowboy.’ Huge fan, Nick J.”

Nick, thank you for that just on entertainment value, and I haven’t checked out that “Unicorn Cowboy” episode yet, but I’ll be looking for that too. I think Masayoshi Son is a typical example. We saw people in the financial crisis who anticipated and they took the right position. John Paulson was one of them, Michael Bury was another one, just very smart guys who’ve been around the block and figured it out and got positioned right and made a ton of money, just tons and tons of money, billions in Paulson’s case.

There was also the economist Nouriel Roubini who kind of predicted the whole thing. But then after that, it wasn’t like they were knocking it out of the park every year or two. They had some slips and trips and things didn’t necessarily go as super duper well for them as it did in the crisis.

I think Masayoshi Son is like that. He made a bunch of money in tech companies and telecom in Japan and stuff, and now he thinks he’s going to do it again with WeWork and Uber and Slack and all these things that are in the SoftBank vision fund, the $100 billion vision fund. And he thought he was going to start a second vision fund and he wasn’t able to do that because the first one is all of a sudden not working out so great.

So, that’s my take on him. I don’t know if he has a disorder, but I’m sure I’m going to listen to what NPR says on their “Unicorn Cowboy” episode to find out what that disorder might be. Thank you, Nick for that, and thank you everyone for listening.

That’s another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast. It’s my privilege to come to you this week and every week. Thanks so much for listening. Listen, you can go to InvestorHour.com and put your e-mail in there and get all the updates for all the future episodes. You can also go to InvestorHour.com and you can listen to every single episode we’ve ever done, and you can get a transcript of every single episode we’ve ever done. Kind of cool, right?

So, by all means, do that. Go to InvestorHour.com. Have a good time listening to past episodes, and I will talk to you next time. Thank you very much. Bye-bye.

Announcer: Thank you for listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to investorhour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail at [email protected].

This broadcast is provided for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

[End of Audio]

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.