Following the Hertz Herd Off A Cliff

In This Episode

Dan starts off this week’s rant focusing on some crazy news the Fed just announced. Could we see a sideways market over the next five years? If you think it’s impossible, just know it’s happened before.

Plus, Dan takes a look at Hertz’s insane new prospectus and highlights some of the gems. The company readily concedes that these shares will end up worthless, yet millions of shares are still being bought to this day.

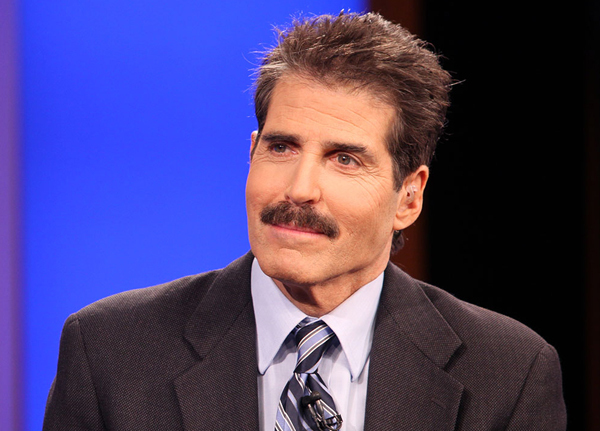

Then on this week’s interview, Dan brings 19-time-Emmy-winner and winner of 5 awards from the National Press Club, John Stossel, onto the podcast. John has been one of the biggest names in TV consumer reporting over his incredible 50 year career, working for both ABC News and Fox Business Channel. John also has written several books, most recently, No They Can’t! Why Government Fails but Individuals Succeed.

During their interview, John tells Dan why he has left the mainstream media circle and created StosselTV on www.JohnStossel.com. They also discuss other hot button topics like the nanny state, trouble with policing in America, and the Coronavirus. You won’t want to miss this interview.

On this week’s episode of the mailbag one listener asks Dan, what happens to the crypto network when miners no longer receive compensation for their work? Also, are there any specific parallels from the Dot Com crash to today’s market environment? And why do some bankrupt companies actually stay above zero?

Dan answers these questions and more on this week’s episode.

Featured Guests

John Stossel

American television personality

John Stossel, American television reporter and commentator, best known for his role on the ABC newsmagazine 20/20.

Stossel graduated from Princeton University in 1969 with a B.A. in psychology. He soon began a career in television journalism, working initially as a researcher for KGW in Portland, Oregon, and then as a consumer reporter for WCBS in New York City. He worked as a consumer editor for ABC's Good Morning America before becoming a correspondent for 20/20 in 1981. In time, Stossel's role on the program expanded, and his occasional segment "Give Me a Break," in which he skeptically examined topics ranging from education to government regulation, eventually became a regular feature of the show. In 1994 "Give Me a Break" was transformed into a series of one-hour prime-time specials that enjoyed consistently strong ratings. In 2003 ABC named Stossel a coanchor of 20/20.

In 2009 Stossel joined the Fox News Channel and Fox Business Network as a special series host, author of the blog John Stossel's Take, and anchor of the weekly news program Stossel (2009-16), focusing on libertarian issues.

Stossel's reporting garnered numerous awards, including Emmy Awards and a George Foster Peabody Award. In addition to his activities in broadcast journalism, he promoted Stossel in the Classroom, a video designed to help teachers develop their students' critical thinking skills. Stossel also wrote Give Me a Break (2004), Myths, Lies, and Downright Stupidity (2006), and No, They Can't: Why Government Fails--But Individuals Succeed (2012).

Episode Extras

NOTES & LINKS

- To follow Dan’s most recent work at Extreme Value, click here.

- To check out John’s research and insights, click here.

SHOW HIGHLIGHTS

1:32 – Earlier this week the Fed announced they will start buying individual corporate bonds. Dan explains why this is bad news for the U.S economy.

9:55 – Is it time to put investor cash to work? Not so fast. “…The more they intervene, the more cautious I get and the more I’m convinced we’ll see, at least 4-5 years of sideways nastiness.”

11:20 – Dan dives into the new Hertz prospectus. What can new shareholders expect from their new holding? “When the bankruptcy works out the common stock will very very likely be worth diddly, zero, squat, nothin’…”

17:12 – Dan has a conversation with today’s guest, John Stossel, a reporter who starred for many years on both ABC News and Fox Business Channel. John has received 19 Emmy Awards and five awards from the National Press Club over an incredible 50 year career.

22:30 – John explains what shaped his views at a young age. “I discovered Reason Magazine the libertarian magazine, and that was a shock… Here are these people who understand this sensible philosophy way more than I do, and I want to learn about that.”

27:31 – Dan plays devil’s advocate with John on the subject of the Coronavirus, “Surely you understand that lots of people could die if we don’t shut everything down, right?”

31:20 – John shares a few examples of nanny-state intrusions that legitimately do save lives. But he also explains why these innocent measures are often taken too far.

34:15 – How bad is the police problem in America? John shares the main reason tensions have been heating up. “Since the police unions stop almost anybody from being fired, and everyone from being fired until recently, that’s dangerous.”

39:19 – Dan and John discuss a big reason the government keeps growing… “It makes it inevitable that people are always going to be trying to grow government to fight some emergency, doesn’t it?”

44:51 – John shares one way he aims to help impact the younger generation… “And now we have these hundred thousand-plus teachers who every year play some of the videos in class and have discussions…”

49:56 – Dan asks John for one final thought… and he delivers with one way you can have a big positive impact on the future of libertarian ideas today.

52:09 – On this week’s episode of the mailbag… what happens to the crypto network when miners no longer receive compensation for their work? What actually caused the Dot Com crash of the Y2K era? Are there any specific parallels to today’s market environment? Why do some bankrupt companies actually stay above zero? Is a company’s book value a good fundamental to look at nowadays?

Transcript

Intro: Broadcasting from the Investor Hour studios, and all around the world, you're listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music playing]

Tune in each Thursday, on iTunes, Google Play, and everywhere you find podcasts, for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive, at InvestorHour.com. Here's your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello, and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value, published by Stansberry Research. Today we'll talk with John Stossel – you know, that libertarian guy who used to be on ABC News. We'll talk with John about what's happening in the world today, and how he's getting his liberty-focused message out today. This week in the mailbag, listener Pete L. tells us how he beat the S&P 500 by 10%, year to date. And I'll call in my crypto posse, Eric Wade and Fred Marion, to help answer a very deep question about bitcoin from listener Jonathan H. In my opening rant, this week, I'll sing a little bit of an old 1980s classic, and then I'll tell you why I'm doing it. And we'll talk a little bit more about the Hertz bankruptcy. That and more, right now, on the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music playing]

[Sings] Turning Japanese, oh, yes, I'm turning Japanese, I really think so. That's all I'm going to sing. I'm not a great singer – not at this hour in the morning anyway. Why am I singing a 1980s classic, "Turning Japanese"? Because I think the U.S. is turning Japanese – at least, the central bank is turning Japanese. What do I mean by that? Well, earlier this week, the Fed said it's going to start buying individual corporate bonds. And of course, Japan has been over this ground – they're about a decade ahead of us.

Back in 2002, they had deflation, you know, it was ripping the economy up, and, of course, ripping the stock market up, and that's when sort of the ruling party, the political party back then, kind of strongly suggested that the Bank of Japan might want to buy some equity ETFs. They didn't do it right away. Around 2009 – we know by 2009 – the Bank of Japan was buying corporate bonds, OK? Like what the Fed just recently decided to do. But in October 2010, they just, they weren't happy with the recovery from the financial crisis, so, the Bank of Japan rolled out a new asset purchase program that included equity ETFs.

And it's been a mixed bag. It winds up being, like, you know, when the market is really tanking hard, it seems like it helps out. Like, back in March, Bloomberg reported, back in March, the Japan Topix index did better than the S&P 500. The Topix lost 6%, S&P 500 lost 12% – might have something to do with fewer COVID-19 cases, might not, but it's sort of been like that the whole time. So, it's weird, though, because they own – according to JPMorgan, Bank of Japan is going to wind up owning, like, a fifth of five of the largest corporations that trade in Japan. You know, what was it we talked about in college, when they would talk about what socialism is, "Well, it's, you know, ownership of the means of production." The government owns everything.

Well, who would've thought that this is how it would come about, [laughs] with an otherwise seemingly, you know, pretty open economy, capitalistic type country, you know, buying, acquiring the means of production. Like, making the country more and more, technically, socialist, by lapping up equity in the stock market, because they're trying to spur on a risk-taking mentality. And to me, that's one of the big lessons of the Japan experiment with buying corporate bonds and equity ETFs to the point where they're owning almost a fifth of these companies. The lesson is: it kind of doesn't work. It's the opposite – it's really, it winds up being a symptom of what's going on.

It's a symptom of the lack of a risk-taking entrepreneurial mentality. It doesn't spur that. It just reflects the same lack. And it's almost like people look at the Bank of Japan, you know, people in Japan, and they say, "Well, as long as they're doing this, we know something's wrong, so we're going to behave accordingly." And I think that's what happens in the market. I think that's, in fact, how you get to negative interest rates, because the central bank doesn't send rates to zero and below because everything's just swell. No, they do it because they're worried as hell that they're going to see a big deflationary event, and they want to spur risk-taking, and they want to support asset prices, and, you know, make it cheap to lend, as well.

So they figure that, you know, they go into the bond market, they print money, go into the bond market, press rates down, and they expect, "Well, it'll be easier for people to borrow money. It'll stimulate consumer demand. Isn't it wonderful? Blah blah blah," and it just doesn't turn out that way. And frankly, you know, this is why I've been talking about doing your homework and reading up on the period from 1929 to 1945. It's not because I think we're going to have another Great Depression. It's just because I'm highly suspicious of any kind of a long-term really wonderful outcome by all of the intervention.

That's my real message. So, it's not, like, "Hey, Dan says this is going to be another Great Depression." No, Dan thinks you should study that period, because the hallmark of that period was enormous intervention by the federal government in the United States. And, you know, as distinct from, you know, there was Calvin Coolidge, right? Silent Cal, and then there was Hoover, right, and the Great Depression started under Hoover's watch, the Crash happened under Hoover's watch. But he gets the wrong rap, historically. People say, "Well, he didn't do enough, and FDR had to come in and fix it." It's not that way at all.

He did plenty. He believed deeply in the government's ability to intervene, and did so. FDR, you know, part of his initial platform was, "I'm going to cut spending. You know, we spend too much, in this country. We need to be more fiscally conservative," [laughs] or whatever. So, he was just saying – he was a pure politician who just said what he thought people wanted to hear, at the time. He said what he needed to say to get elected, and then, of course, those first 100 days with, you know, the National Industrial Recovery Act and all this stuff, devaluing the currency, the Civilian Conservation Corps – there's, like, a whole bunch of stuff, that happened in the first 100 days, that screamed massive big government intervention into every aspect of our lives.

And that really is, for me, when the modern era of massive government intervention began. So, I fear that. I fear that we're getting to this place where we're – we're already seeing it, right? The government shut down the economy, and then launched a whole bunch of stimulus, and the Federal Reserve launched, you know, a bunch of stimulus at the same time, and it's all, ostensibly, to, you know, protect us from dying of coronavirus. I think we've since seeing that you can't shut down an economy, and that the virus is not nearly as horrendously bad as everyone said it would, with millions of people dying. It's not that way at all.

So, they've made a mistake, but you know how these things go, the interventions will continue. I mean, as I talk to you, there's word of a trillion-dollar infrastructure program, and of course all the infrastructure stocks are going straight up – you know, five or 10% – a spike. So there's going to be lots of intervention, and my point of all of this and studying that period is, and of us, you know, going Japanese, is that it doesn't work. You know, we're going to go sideways, economically and in the markets, and it's going to be really, really difficult. And it's difficult now.

I've talked about this for a couple years where I was saying it was top-y, right, I was bearish starting in May of 2017, and continued that way until, like, late March, early April. And then I've had to get that way again, because we're right back at the all-time high valuations, just about, in the stock market. So, around tops or, you know, approximate tops – I'm not calling it top is all I'm trying to say. But when the market has this top-y action, it's hard to trade. Stanley Druckenmiller is having trouble with this, so, you know, what are you going to do? And it's been crazy – it's crazy whipsaw. You know, the government says, "OK, you know, we're going to stimulate the economy," the Federal Reserve says, "We're going to buy corporate bonds," well, the market goes straight up.

And then what did it do? It didn't stay there for long, did it? It's a whipsaw, you know, based on whatever news is coming out at any particular time. It's really, really difficult to trade. So, you know, I'm going to keep singing my song of cash, gold, bitcoin, buying value, buying high-quality businesses, only when you can get them at a reasonable discount to intrinsic value, until I have reason to say something else. Until I have reason to say, "You know, you don't have to be so worried, anymore." Maybe if the market's down 50% to 60%, I can say, "Hey, put some of that cash to work, and maybe even sell some of that gold and put that to work."

But I'm nowhere near there now, and the more they intervene, the more cautious I get and the more I'm convinced that we're going to see at least four or five years of sideways nastiness. I told you about Collin Roach, the macro guy we interviewed a while back. But on Twitter he said, you know, during the Spanish Flu, the market went down 25% or whatever, then it went sideways for three to four years. And we could easily be seeing that, that's a reasonable expectation today. And I think 10- to 12-year S&P 500 returns flat or negative is a possibility. So, you know, somewhere in that neighborhood of five to 10 years, you'd better – you'd better know how mitigate this. You'd better hold your cash, gold, bitcoin, value stocks, over the next several years, because I think, you know, if you try to buy growth and, you know, all these wonderful things, if you try to speculate the way you have for the last 10 years, you're going to get hurt.

All right, that's enough of that for right now. Just be cautious and be suspicious of all this intervention. I want to talk about one more thing before we move on and talk with John Stossel. Remember we talked about Hertz and all these poor, sad fools on Robinhood buying Hertz shares when the company has declared bankruptcy. Well, [laughs] Hertz was smart: they took advantage of all this craziness, and they're going to offer up to $500 million worth of their common stock. And of course, when people do a common stock offering, what do they do? They issue a prospectus. So, let's do a little deep research, live on the podcast, and dive into the Hertz prospectus.

It doesn't take long before you get to this – reading from the prospectus, right now: "We are in the process of Chapter 11 reorganization cases under the bankruptcy code, which may cause our common stock to decrease in value, or may render our common stock worthless," OK? Then, in the paragraph under that sentence, they talk about a bankruptcy plan, OK? And they talk about the bankruptcy plan, and "recovery of our business from COVID-19 pandemic, if any." And then they say here: "Although we cannot predict how our common stock will be treated under a plan, we expect the common stockholders would not receive a recovery through any plan, unless holders of more senior claims and interests such as secured and unsecured indebtedness, which is currently trading at a significant discount, are paid in full.

"Which would require a significant and rapid and currently unanticipated improvement in business conditions, blah blah blah. We expect our stockholders' equity to decrease, as we use cash on hand to support our operations in bankruptcy. Consequently, there is a significant risk that the holders of our common stock, including purchasers of this offering, will receive no recovery under the Chapter 11 cases, and that our common stock will be worthless." They're selling you common shares and saying, "Hey, probably going to be worthless, but here you go." [Laughs] And if you look at – just get a bond quote, what do you find out? Well, you find there's a bunch of stuff trading at 44 cents on the dollar, 43 cents on the dollar, and a handful of Hertz bonds trading for, like, 99 or 100 or 101.

Well, what's that all about? I'll tell you: those 99, 100, 101s, they're the senior secured obligations. They're the people who know that "in bankruptcy, we get paid first... we get paid before absolutely everybody." And those ones that are trading for, like – actually, there's a couple around 78 and 76, and then, there are some trading for 44 and 43 like that. Look, anything under 90, you're in a bad place, OK? And when you're under 80, oo, and you're under 50, forget it – forget it. Those people are discounting – you know, what they're saying is, "Well, in bankruptcy, maybe we're probably going to get, you know, 45 cents on the dollar, and that's about what we're – " Let me tell you something: if those guys that far down the capital structure get 45 cents, you know what the equity holders get? Diddly-frickin'-squat.

And the Federal Reserve can't save you [laughs], you know? They could buy anything they want – it doesn't matter. When the bankruptcy plans out, the common stock will very, very, very likely be worth diddly-zero-squat-nothing. And, you know, we mentioned, like, Chesapeake Energy Corps? Same deal, only, here's some of the Chesapeake bond prices. So I'm looking at maybe, I don't know, looks like about 15 or 16 bonds, here, and there's one, two, three, four of them trading right around 100. So, right, those people are expecting – those are the senior secured bonds, and those people are expecting to get all of their money back in the bankruptcy.

And here's some of the other bond prices. Well, there's a couple at 44 and 45, but here's the rest of'them: five, seven, 3.75, five, four, five – that's five cents on the dollar, 3.75 cents on the dollar, one of them's 1.75 cents on the dollar. Those people are counting on – they're going to get wiped out. So, what do you think is going to happen to the equity? Gone, right? The equity is at the bottom of the capital structure. From the perspective of bankruptcy, its purpose is to get wiped out, so that they can have something leftover for the bondholders. All right? Don't buy this stuff.

I mean, look, Warren Buffett owned USG when USG went bankrupt – actually, you know something, I'm going to answer a question on this in the mailbag. So let's just leave at that: just don't buy Hertz, all right? [Laughs] Just don't do it. OK, let's talk with John Stossel right now, let's do it.

[Music playing]

Former hedge fund manager Whitney Tilson says we are setting up for a huge rally, later this year, and he is encouraging you to learn how to position yourself accordingly. Tilson thinks he has found the next big tech trend that will make investors rich. It's called TaaS, and if you haven't heard of this technological breakthrough, you soon will. Over the next few years, TaaS will change the way you eat, shop, work, and travel. It will change the value of our homes and where we live. It will radically alter prices for airline and train tickets, gas, and even household goods. It could even help slow the spread of the coronavirus, and help get the American economy moving again.

Whitney put everything you need to know in a simple presentation, where you'll even learn the name and stock symbol of his favorite TaaS investment in the world, today, for free. Go to www.TilsonPodcastOffer.com.

[Music playing]

Our guest, today, is John Stossel. John Stossel has been a reporter for 50 years. In his first job in Portland, Oregon, he helped invent TV consumer reporting. Then he moved to WCBS in New York City, then to 2020 and Good Morning America on ABC. Stossel went on to become an ABC News correspondent, joining the weekly news magazine program 2020, where he became co-anchor. In October 2009, Stossel left ABC News to join the Fox Business channel. He hosted a weekly news show on Fox Business called Stossel, from December 2009 to December 2016. He has received 19 Emmy Awards, and 5 awards from National Press Club.

Stossel has written three books: Give Me a Break, Myths, Lies, and Downright Stupidity, and No, They Can't: Why Government Fails – But Individuals Succeed. After seven years at Fox, Stossel left to start Stossel TV, which you can find at JohnStossel.com, where he makes videos to teach young people about free markets. They make about one video per week, averaging about a million views each – nice. Roughly, 10 million students, per year, discuss liberty and free markets, as part of the "Stossel In the Classroom" program.

John Stossel, welcome to the program, sir.

John Stossel: Thank you. Good to be here.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, a reporter for 50 years – you don't look a day over 50, John. That's pretty impressive.

John Stossel: Yeah, I'm some kind of freak.

Dan Ferris: Well, you know, you're a freak in another way, that I noticed a long time ago when I started watching you on TV, I thought to myself – the first time I saw you and you were reporting on some libertarian-themed idea, I thought, "Well, this is a fluke, I'll never see him again, or his boss will say, 'Uh, that was a terrible story, we're never going to do that again.'" But then you came back, again and again and again, and you became the libertarian guy on TV. And I've read a little bit about what it was like behind the scenes, but I just, every time I saw you on TV, I wondered, "How is he getting away with this?" when you were on ABC, especially. How did you get away with it? How did you last so long, reporting libertarian themes?

John Stossel: Well, they didn't like it. I was good at doing TV news stories, and I could make things interesting and explain complicated things in entertaining ways, and got pretty good ratings, so they kept me. They hired me as a consumer reporter, and I was bashing business, and they, of course, liked that. And when I finally woke up and saw the government does more damage than business ever does, and focused on pointing out the excesses of government, they did not like that. But they wanted to keep me, and I just fought to do those stories. And eventually, they didn't like them anymore [laughs], I wouldn't do it anymore, and that's when I left for Fox. But for – I was there 28 years, and I was a libertarian maybe for 15 of them, and, you know, half the stories I wanted to do, they let me do.

Dan Ferris: Oh, half, OK, [laughs] all right. So, I've been reading about you, I read about half of your book No, They Can't, and, you know, just reading about you online and things. And of course, I've seen your work over decades, and I wonder – I know you discuss some of what changed your mind about politics, but was there a moment or a person or a book – you said 15 of those 28 years you were a libertarian. After 13 years, did you meet someone? What happened? What made John Stossel become a libertarian?

John Stossel: I watched the liberal solutions fail. I came out of college at the time that the War on Poverty was beginning, and my professors has taught me, "Look, it's despicable, in this rich country, that some people are so poor, and we can fix this with the right programs." I totally believed. But then, as a young reporter in Portland, Oregon, I watched those programs not work, that they would give people money or training, and the training was lousy, and the people who got money now were classifying themselves as victims, and they were mad because they weren't getting more money, or the next guy was getting more money. And of course, there were the disincentives because you got less money if you were married than if you were a single mom, so when the welfare worker would come by, married moms would just get the man out of the house.

And the government solutions always had these unintended side effects, and they were worse, so, the liberal media I'd been drinking no longer made sense. I started reading conservative media, but they seemed to want to go to war with everybody and police the bedroom – I didn't like that. And then, I discovered Reason magazine, a libertarian magazine, and that was a shock that, "Oh, my god, here are these people who understand this sensible philosophy much better than I do, and I want to learn more about that." And I became a born-again free-market zealot.

Dan Ferris: Wow, that doesn't happen often. You know, I was thinking about, if I had to label myself, I would definitely call myself a libertarian. And I thought of it the other day – you know, I'm encouraged by the increasing number of these people in the world, you know, there need to be more of us, I think. But I was thinking, the other day, that when I was a kid, you know, there were three TV stations, right? And then, there was this other fourth one, it was like the UHF channel that came in some times and didn't come in other times. And I still feel like libertarianism is that UHF channel that doesn't always come in, and it doesn't always broadcast, and people don't hear it, and, you know, some people don't even know it's there.

And I still feel like we're not making a lot of ground. How do you feel about that? Do you think libertarians are making any ground? Do you think we're influencing anybody, politically?

John Stossel: Well, anybody is an easy question. [Laughs]

Dan Ferris: Sure, sure.

John Stossel: Sure. [Laughter] I make videos – a video a week – and I'm averaging almost two million views, so, some people are into it. But I agree, we are not making much ground, and I – I've stopped being shocked, but I was shocked. Because once I saw the light, I naively assumed that, "God, all I have to do is explain what I learned, and people will say, 'Oh, yeah, that makes so much more sense.'" But they don't. Some people's brains will just not take this in. My wife and I fight over this stuff. I've been trying to convince her for 35 frickin' years, and there's still a new argument whenever she reads the New York Times.

Dan Ferris: [Laughs] Yeah, I feel your pain on that one. I think, though, you know, I was looking through your book, No, They Can't, and you did a neat little device, in here, that explains a lot of this problem, I think. And every, you know, couple of pages, you've got a new section, and it starts with a little box, and in the little box it says, "What intuition tempts us to believe versus what reality taught you." And an example here is: seat belt laws save lives, that's what intuition tempts us to believe. What reality taught me: seat belt laws also cost some lives, and nobody ever talks about that. And, you know, that's a fairly controversial opinion, and all those little boxes in the book have fairly controversial opinions. [Laughs] But people, they don't think, do they?

It's part of the problem, here, is that they go with their first gut reaction. And when it comes to who to vote for, it's, like, "Who looks good on TV and sounds good?" not, "Who makes sense?" But there really is no solution for that, is there?

John Stossel: I hope there is, but I haven't found it.

Dan Ferris: Right, it's – the solution is kind of to go at another problem, I think, and I think you've done that rather well. You know, you're not running – in other words, John Stossel is not running for office. He's educating.

John Stossel: Right. I would suck at running for office, because I have no patience, and I can't smile at strangers and ask them for money. But by making these weekly videos, you know, people – I left my Fox TV show because I wanted to reach young people, and my son said, "Dad, you know, people aren't going to believe – aren't going to trust what you say about markets, when you're on Fox. And you don't need a network, anymore. You've got a million Twitter followers, and with social media now, you can reach people." And they do, young people do watch short videos, so, we're at least making people aware that there's another way to think about these things, that the answer isn't always another government program.

And then the videos go to school teachers – there's a nonprofit that offers them free, Stossel in the Classroom – and probably 10 million high school students, some middle school students, watch them in class. So, even if they forget them or we're not convincing them, they at least know there's an alternative to state control.

Dan Ferris: Right, it'll be somewhere in their consciousness. So, John, you mentioned, you know, giving people another way to think about these things. Give me another way to think about government's response to the coronavirus pandemic. Surely, John – I'm going to play devil's advocate – surely, you understand that lots of people could die, if we don't shut everything down, right?

John Stossel: Yes, [laughs] of course. And this is a tough one for libertarians, because there is a role for government, and an epidemic and keeping an epidemic under control so that hospitals aren't overwhelmed is almost certainly a job that government should try to do. And as always, they make mistakes, and in this case, they focus on the lives they might save by reducing the contagion by ordering people indoors. They don't – it's the seen versus the unseen: they can count the COVID deaths, but how many people die because the economy goes down and people are depressed? My first TV special for ABC, Are We Scaring Ourselves to Death?, pointed out that there's good research that the biggest extender or shortener of lives is wealth.

And poor people drive older cars with older tires, they can't afford the same good health care. In Bangladesh, floods kill thousands of people... In America, they don't kill anybody, except for Katrina, because we have cars with which to drive away, and radios to hear about the floods, and dikes to divert the water. Wealthier is healthier. So when they shut the economy down, they kill people, too. Now, can we measure, are they killing more than they're saving? I don't know, but I wish the hysterical media would talk about it.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, [laughs] I don't think you're going to hear about it from them. I want to run a thought by you. I said this on a recent episode of the podcast, and maybe these two things don't have anything to do with one another, but I find them suspiciously juxtaposed in time, at least. You know, on the one hand, we seem obsessed with kind of babyproofing the entire world in response to the pandemic, we want to babyproof the entire world for every toddler and octogenarian on the one hand. And then on the other hand, we have wound up with violence in the streets and protests in, actually, 350 cities, by one report. Maybe I'm wrong, maybe I'm just making up a correlation, but I feel like in a society where you clamp down this hard to try to make things safe, you're really making things a lot more dangerous.

On the one hand, if you clamp down too hard on society, you upset the balance, and you try to – we've tried to make things too safe. And we try to make things too safe in a lot of ways, and your mention of scaring ourselves to death sort of reminded me of this, too. It seems to me that a somewhat logical outcome of trying to make things way too safe is that you, in fact, make them a lot more dangerous, even if you're talking about an entire society. So, if you inhibit my activity so much that you've basically waged war against my ability to make a living and support my family, of course I'm going to take to the streets and bur things down, you know, if I'm a typical weak-willed human being.

John Stossel: It's just a very broad topic. You brought up seat belts, earlier. Now, that's an example of making things less safe, somewhat less safe, by trying to make them more safe. In that, once you require seat belts – first of all, seat belts would've happened anyway – they were already coming before they were made mandatory. But when people wear seat belts, we drive faster. One, there's something called the Peltzman Effect, after the University of Chicago economist who proposed it, he said the best safety device, instead of a seat belt, would be to have a spike aimed at the driver, mounted on the steering wheel, because that would make you drive much more carefully. And we are more reckless with seat belts.

On the other hand, seat belts clearly do save lives, because cars are really dangerous, and the seat belts do make a difference, there. So that's one Nanny State intrusion that almost certainly has saved lives. But as they continue to add more, they probably do cost lives. One, because they make us poorer, and wealthier is healthier, and also because they make us just less self-aware. We trust that, "Oh, everything must be safe, because there must be regulation for this," so, we don't check. But [glitch interferes with audio] riots, are these riots happening because the economy is worse, because the government over-shut it down? I think these riots are mostly about race, plus, progressive bad media propaganda.

Dan Ferris: Do you think we genuinely have a police racism problem, you know, a problem where the police are targeting certain races?

John Stossel: Some – you know, most cops don't, but a few cops do. And cops have a lot of power. I really noticed it doing a 2020 story on fake cops. There was an outbreak, in parts of the country, of people ordering mail-order uniforms and fake badges, and pretending to be cops and robbing some people, raping some women. And to illustrate it, because it's television, I, of course, sent for the mail-order cop uniform, and walked around a town. And it was amazing how it affected me. I felt extra macho. The way people looked at me and deferred to me made me feel very powerful.

And if I were a little bit of a sadistic asshole, I could see how I would really abuse that power. So you got hundreds of thousands of cops... If only half or 1% of them is a sadistic jerk, that's a lot of powerful sadistic people, or racist people, who will be doing a lot of nasty things to people. And since the police unions stop almost anybody from being fired, and everybody from being fired until recently, that's dangerous. And so, if you live in a Black community, you get hassled a lot. While it's true that the cops don't shoot Blacks more than whites, percentagewise, they are, statistically, more likely to handcuff you, throw you up against a wall, search you, if you are Black. And Black young people, just about everybody has been unfairly, they feel, stopped by the police at some point in their lives, and we white people rarely experience that.

Dan Ferris: One thing that I have noticed – I've tried to research it and I haven't made much headway – I don't like drug prohibition, and I've watched this TV show called Live PD, and the cops – it's a live cop show where they follow people around. The cops pull somebody over, it's almost always a Black or Hispanic person, and they walk up to the window of the car, and they say, "[Sniffs] I smell marijuana." And that constitutes probable cause to put the person in handcuffs and rip the car apart. And I feel like a lot of this harassment is about drug prohibition – and guns, too – they're looking for drugs, guns, and cash. A large amount of cash or just a pipe or a scale, like a kitchen scale that you would use to weigh things, you know, for a recipe, is all considered drug paraphernalia.

And, so, the law, I feel like the law promotes this abuse, does it not? It makes that swaggering guy – gives that swaggering sadistic guy an excuse, doesn't it?

John Stossel: Yes: more law, more crime. And you've got to have some law, and it's the job of the state and the police to keep us safe, but the drug laws and – there's a website that lists the insane federal laws, the bar association tried to count them, and they couldn't even count them. And so, all of us are breaking – all of us who are busy doing things, building something, we probably are breaking some laws, and if the cops wanted to get us, they could. But the problem is that nobody goes to work at the EPA, unless you're an environmental zealot who wants to pass more rules. No group of schoolkids goes to the state house to meet their legislators and asks, "What laws have you repealed?" They all ask, "What laws have you passed?"

So, Thomas Jefferson said it's the nature of things for government to grow and liberty to yield, and that happens. And that gives us more laws and more lawbreaking, higher jail costs, more problems.

Dan Ferris: Well, if you're trying to fill me with hope for the future, John, I'm afraid you're not doing a good job of it, right now. [Laughter]

John Stossel: Yeah, sorry about that. On the other hand, life, it gets better. In spite of all these bad things going on, the animal spirits of the economy have grown as fast as the suffocating growth of government, and that plus innovation means most people's lives get better. And, heck, billions of people have been lifted out of the mud and misery of terrible poverty, over the past 30 years, because of capitalism. So, let's not forget that good news.

Dan Ferris: But, John, isn't capitalism evil? Doesn't it exploit people? Isn't that the problem, today, is that all these, you know, businesspeople get bailed out, and poor people are still poor?

John Stossel: It's a problem when businesspeople get bailed out. Real capitalism is, you don't [laughs] get bailed out – you're free to fail. So that's crony capitalism and that's not good, but I just am dismayed, listening to my educated liberal friends argue that capitalism is the problem. It's not.

Dan Ferris: You know, I think one of the problems that libertarians have is that – and I saw this mentioned in your book No, They Can't – is that, you know, in the news, they always wanted you to cover something that was happening right now, that had a lot of urgency to it. But you said you wanted to cover things that played out over a longer period of time. And in a somewhat similar vein, it seems like folks who are arguing for more government all the time, all the arguments seem to be very tangible and immediate and urgent. And the argument against them appears weak, because it wants to divert your attention to a longer – you know, I think you said in the book, somewhere, you know, nobody says, "Incremental improvements – "

Nobody marches down the street with a sign that says, "Incremental improvements and quality of life right now," or something. [Laughs] It makes it very difficult, and it makes it inevitable that people are always going to be trying to grow government to fight some emergency, doesn't it?

John Stossel: It does, and I'm glad you picked up on that from No, They Can't, that when something happens, there's innate human tendency to say, "There ought to be a law ought to fix that." And it's hard to fight, and it's harder to see the unintended consequences which may come out over 20 years, and so, the media focus on the immediate solution stuff. And the media is a big part of the problem, and it's not all the reporters' fault, in that, one of the big developments, over my 50 years of reporting, when I graduated, there was the Vietnam War, and the media covered that quite well. And then you look at the big stories of the year, and it's amazing how many of them are nothingburgers.

I mean, the media is hysterical about the Ebola epidemic, and even COVID may turn out to be little. But the stuff that really changed our lives, the invention of the cellphone, the computer chip, Facebook, Google, there was no coverage. Because there was no single place it was happening. When the mayor holds a news conference, you can go and you can cover it. But when entrepreneurs all over the world are inventing something, we don't have the resources to cover it, and even if we did, we wouldn't know where to go to cover the stuff that happens slowly.

Changing attitudes about gays, the women's movement, we can cover the march, but you can't cover all the subtle differences in people's opinions that happen slowly over time. But that's the big stuff.

Dan Ferris: You know, I talked to Ron Paul, recently, on this show, and he was much better at making me feel optimistic, John. [Laughter]

John Stossel: Sorry about that, yeah, god bless Ron Paul [crosstalk].

Dan Ferris: Yeah, but really, really, I jest, because I think – you actually do make me feel optimistic, because part of what we're saying, here, I think, is that – well, for example, if you focus on the news, that's part of people's problem is that they get all their information from the news, so they're always having this urgent, "Government must do something," message thrown at them. You know, folks like you kind of, you quit the news, and you [laughs] went and made your own website, so that's – to me, that alone is something to be optimistic about, that people like you would kind of quit doing, you know, a show on the news, which was actually a libertarian show, and educate young people. So, I just want you to know [laughs] I'm just joking about the optimism thing.

Where does John Stossel go from here? Are you just going to keep doing these videos and keep educating young people? This is your mission, now?

John Stossel: Yes. And I hope your listeners will make a little tax-deductible – or a large one – donation, to help me [laughs] keep doing it. We've got an office with five people – well, we had an office. Now we're doing it remotely – and we produce a video every Tuesday.

Dan Ferris: Tell me, also, a little bit about – I didn't get a chance to really look into the Stossel in the Classroom program? I mean, 10 million kids are talking about liberty and, you know, free markets – what are you doing? You're sending them videos? You're sending them, like, videotapes or something, or e-mailing them videos?

John Stossel: It started with videotapes, that I would get letters at ABC, from teachers, "Oh, I wish I had taped that. That's such a good explanation of this economic principle, and I would've loved to have shown it to my students. Can I buy it?" and ABC was selling them for $95. And so, I was a [glitch interferes with audio] libertarian who formed a nonprofit that started offering them to teachers for less. And then we discovered that teachers don't buy anything on their own [laughs], and so, we raised more money and started offering them for free.

And we tried to go through the big teachers' conferences and the teachers' unions just killed us, they wouldn't even allow us to have a booth, many places. But through mail-order and word-of-mouth, word spread among teachers, and over 15 years, we gradually built up to a list of about 120,000 teachers who liked the videos and would use them in class. Then we added teaching kits for them, and the state standards kept increasing, we added instructions on how they would meet your state standards. And now, we have these 100,000-plus teachers who, every year, play some of the videos in class, and have discussions. Now, I don't know what the students learn, maybe they sleep through it, but at least some of them figure out that, "Gee, there's another side to this."

Dan Ferris: Yeah, again, it's just sort of, it's just like with your career, I feel like I want to ask how is this allowed to exist. Are these all private schools?

John Stossel: I would've expected that. No, mostly public schools, and – I don't know where you're located, but it surprised me, but in much of the country, government-run schools have some libertarian-friendly teachers, too.

Dan Ferris: I live on the left coast, I live about just a few minutes from downtown Portland, Oregon. I live over the border in Washington.

John Stossel: Vancouver.

Dan Ferris: Yes.

John Stossel: Yeah, I used to – I got my first job in KGW TV in Portland, so I know about that. And, yeah, you live in this world where nobody agrees with us, and it can be very unpleasant.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, I have to say, I mean, I have few friends, I mean, all I have to do is make – you know, show up at one of the neighborhood gatherings or something, and you make one little comment about how the government shouldn't be involved in something, and people look at you like you have three heads. The thing that shocks me is, it's not even that I'm disagreed with. Disagreement is great, let's disagree all day long. But it's that you're just shut down and kind of pushed out, and the view is – it's as though you've advocated genocide or something, it really is that – you're looked at as that horrible. And I know that sounds hyperbole, but it's the way it is. I mean, do you get that?

John Stossel: Yeah, "How can you argue that Trump's slashing of regulations is a good thing?" "Well, because we have too many regulations." "Yeah, he slashed the environmental regulations, you know, like, clean air?" There's real anger behind it. And by the way, [glitch interferes with audio] slash any environmental regulations, he just removed some of the additional ones the Obama environmental regulators planned to add, and – you know, EPA _____ was a good thing. The air and water were filthy. But now it should stand for "Enough Protection Already." But they always want to add more.

Dan Ferris: Right, as soon as you start that good thing, you know it's going to grow into something ugly, one day. You know it. It always does.

John Stossel: Government always grows – look at Japan and Germany and their prosperity, in the '60s – why? Why suddenly in those two countries? I say because we bombed them to smithereens, and they had to start over. It's the only way government shrinks and allows for the leeway that – where free people create prosperity. Hong Kong created – went from third-world to first-world in just 40 years. Because the British rulers basically enforced rule of law, they punished people who stole or killed, and then they sat around and drank tea. They left free people alone. And that's the best creator of wealth and safety, but it's not intuitive. Intuitive is, "Let's pass another law," so all these older countries become stagnant, like, it's the way Europe is being passed by younger, newer countries.

Dan Ferris: Philosophically, the idea of "enough" is extremely difficult, isn't it? The idea of enough government is extremely difficult because people look at that first layer that prevents infringements against persons and property, and they say, "Well, this worked, you know, gangbusters. Let's have more." And more – well, we know what more does, don't we?

John Stossel: And one way to fight it is to get people to think in terms of what percentage of the economy should government control or manage, and people would say 10% to 15%. Or what should the tax level be, people say 10 and 15. You tell them, "Well, it's 40, now," so, can't we just keep it at 40 and find – nah, that's a bad idea, because as the economy grows [laughs], the percentage would go up. But if there were some cap, some way to measure that and sell that, that would be a good thing.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, let's not hold our breath for that. John, we're coming to the end of our time, here, and I like to ask all my guests the same question, at the end: If you could leave our listener with just one though, today, what would it be?

John Stossel: Make a donation to Stossel TV.

Dan Ferris: [Laughs] Very good. And they find that where, JohnStossel.com?

John Stossel: Yes.

Dan Ferris: All right, thanks so much, and I certainly hope we'll get another chance to talk with you, sometime in the future.

John Stossel: Nice to talk to you. Have a good day.

Dan Ferris: You, too, John. Thank you.

All right, that was really cool. [Laughs] After watching John Stossel on TV for years and years, the whole time he was on TV, I couldn't believe what I was seeing [laughs], I was, like, "Hey, it's the libertarian guy," you know, and I was always very, very excited to watch him, and talking to him was kind of a thrill. Really enjoying this book, No, They Can't: Why Government Fails-But Individuals Succeed. I'm about halfway through it. And, you know, you think, if you're a libertarian guy, that you know all the arguments and all the ways of looking at things, but you don't and – and it's a really good read. I mean, he's a really good writer, you know, he's been doing these 50 years. And I can definitely recommend it – even though I'm halfway through it, I can recommend it wholeheartedly.

All right, let's see what's in the mailbag.

[Music playing]

Are you being left behind? Most Americans are, and like we've never seen before. The gap between rich and poor is growing at exponential levels and speed. Thousands in our country ascend into millionaire status, meanwhile, surveys show 60% of Americans have less than $1,000 in savings. That's why, for the first time ever, one of America's ultra-successful multimillionaires has gone on camera to explain the real reason for America's huge wealth gap. Plus, the three steps you must take immediately, to make sure you are on the right side of this trend.

Get the facts for yourself, for a better understanding of how this new economy works. Watch this multimillionaire's important new video, and learn the three important steps to take today, free. Go online to www.GrowingWealthGap.com. Visit GrowingWealthGap.com now.

[Music playing]

In the mailbag, each week, you and I, we get to have an honest conversation about investing, or whatever is on your mind. Just send your questions, comments, and politely worded criticisms, please, to [email protected]. I read every word of every e-mail you send me, and I respond to as many as possible. We're going to start, this week, with Jonathan H., and he wrote one that's just so long there's no way I can read the whole thing. I'm just going to read the essence of his question, here. He says: "I think there is an elephant in the room with respect to bitcoin. The biggest concern I have is related to the fundamental driving force of the network. What happens to the network when miners no longer receive compensation for the work they are doing?"

OK, that's the question. And then he spelled out, very thoughtfully, he did some deep thinking, spelled out five scenarios, and I just can't read them all. But then he said, "Reach out to your coin mafia and let me know if they have any thoughts. Cheers and keep up the good work," signed Jonathan H. Jonathan, brilliant question, and I took your suggestion and I went to my coin mafia, and my coin mafia is Eric Wade and Fred Marion from Stansberry's Crypto Capital. And they've been there and done that. Eric has mined all kinds of cryptocurrencies, I mean, he really knows what he's talking about. And Fred, too. They're both really smart about this stuff.

So I'll read you some of what Eric sent me. He said: "When I transfer money overseas using Bank of America, I pay tons of fees, $35, $50, yep. When I send cryptocurrencies, it's a few pennies. I think yesterday, my son paid a whopping $3 to rush a large transfer. So maybe these 'what about the miners' folks are just overlooking how fundamentally different – " and I would say better – he didn't say that – "that cryptos are from legacy banking." So, Fred's comment is very similar. Fred says, "I love that this reader is thinking so deeply about bitcoin.

"That was one of my first concerns when I started learning about it: in 120 years, when the last bitcoin is mined, the network's incentive mechanism will switch exclusively to transaction fees. Fees already produce some income for miners, about 70 cents per transaction, at the moment. When bitcoin is a truly global payments network with billions of users, the fees should be more than enough to entice miners to power up their nodes – " their computers, right? I thought those were two very good answers. It's an attractive proposition just as a payment's network. In other words, the miners will have plenty of incentive, even after all the mining is done.

I want to thank Fred Marion and Eric Wade for chiming in, and Jonathan H. for a great question.

Next is Ron K. Ron K. says, "Based on your Digest write-up from June the 8th, various stocks seem to be going up every day, without fail. It's enjoyable to be in the stock market during this time, but I keep wondering if each day is the day the party is going to end." [Laughs] You and me both, Ron. Ron continues: "What actually caused the dot-com crash of the Y2K era? Are there any specific parallels to compare to today's market environment? Thanks. Ron K."

Thank you, Ron, that's a good question. People ask this stuff, all the time: "What's going to make it fall apart?" I don't even remember – I heard one story about the Y2K era, I will say that. I heard one story that suggested that there were a lot of IPO shares locked up, and that they – as soon as they were unlocked, and as soon as founders started, you know, trading and selling and stuff and the whole float was available in the market, that's when it all fell apart. That was one explanation that I heard about the Y2K era. We're not – I don't think we're in a similar position at all, today, so – who knows. We don't get to know that. That's why I always say, you know, prepare, don't predict. I can't predict the top. I don't know what's going to cause it to fall apart – I don't think anybody really does. You just have to prepare.

OK, next is Pete L. I really like Pete L.'s message. I wish I could read the whole thing – it's a little too long. Pete L. says: "Hi, Dan. There's a lot of bitching, moaning, and general negativity flying around, these days. Sounds like some of these folks have come across the [email protected] address and found you, as a well-spoken generally kind well-mannered guy, to throw verbal garbage at. Stay strong, man." And he finishes up, he explains how his parents sold their seven-store convenience store chain, and he's, you know, he's managing that money, now.

And he says, "By the way, I beat the S&P average by 3%, last year, with my personal portfolio. Thus far, this year, beating the S&P average by 10%, year to date. It helped me gain the confidence to dump our wealth managers that charge one in 10 – " 1% management fee, 10% incentive fee – "at Wells Fargo Wealth Management. We're going to pull seven-digit sum inhouse, next month. I'm confident I can do right by managing this money throughout the future. That confidence has largely come from knowledge gained form listening to Stansberry, and reading it, as well. Thanks, Dan. Pete. L."

Pete, your message stands on its own. I don't need to say one word about that. Thank you for sending it in.

Mike S. write in and says: "On the last episode, you said 99.9% of bankrupt stocks go to $0, and I owned some puts on Hertz to cash in on this. But I also had bought some puts on PG&E energy, and they declared bankruptcy and the stock never went to zero. Can you explain why the 0.1% don't go to zero? I never did quite understand. Love the show. Thanks. Mike S."

OK, so, Mike, I don't claim to be a bankruptcy expert, OK? But I do know that, in some cases like the USG bankruptcy, when Berkshire was holding USG, and, what else, the GGP bankruptcy, which, you know, was a huge multi-bag where you could've bought the thing for 50 cents – I think it eventually traded in the 20s, maybe – and that really made Bill Ackman's fortune for him. So, every now and then this happens, but I think it depends on the type of bankruptcy. Like, with USG, I believe it was all about separating asbestos liabilities from the rest of the company. You know, "There's no reason to ding the shareholder because this is about asbestos. And we're going to separate this off to the side, and call it bankrupt."

And I think the same thing happened with PG&E, with liabilities from the wildfires. So, you know, when there's a special kind of bankruptcy where they're separating this big sort of act of God kind of liability, maybe you don't bet against the common share – maybe. And I think there was a similar problem with GGP – I forget what the issue was – I think maybe it was just, you know, the financial crisis hit it hard, and the assets were worth more than the liabilities, but it was just kind of a – it wasn't solvency, it was liquidity. Put it that way. That was my top-down understanding. But that's the best I can do – you should google it and read more about it, to really get the full story. [Laughs]

Brian L. writes in and he says, "Hi, Dan. I really enjoy listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour. During the Depression and '60s eras, 1960s, access to equity markets and effective market research was limited to a select few, not to mention communication, networking, research, culmination of ideas, and formation of business relationships, which took weeks and months, if not decades. In today's market, access is virtually universal, effective research takes minutes, sometimes, and communication can be instantaneous. While much can be learned from the Depression and '60s eras – inflation, for example – I am wondering whether today's speed and access factors effectively disqualify comparison of these eras when predicting equity outcomes. Your thoughts? Thanks for the great show. Brian L."

Brian, no I don't, because I'm not focusing on those things. I'm not focusing on trading and liquidity and things like that – well, I should take that back, because, obviously, Fed intervention affects liquidity. But what I'm focusing on are the fundamentals that come before all of that stuff, like, however you communicate it, however fast it makes its way through the, you know, news cycle or through the economy, we're seeing similar levels of, you know, what I would call extreme intervention into the economy, like, a whole new level of government intervention. And I don't think that the differences in communication affect that as a fundamental. It all happens faster [laughs], that's for sure, that's for absolute certain, it all happens faster. But fundamentally, no, I don't think it's meaningfully different. It's a reasonable question to ask, though.

It's similar to when people say, you know, the Bill of Rights or something, and they'll say, "Well, you know, that was in the late 18th century. Everything's different now, isn't it?" And I would say, no, human beings are still human beings, and all of it applies, every bit of it.

OK, David L. writes in and he says – he says he's sorry to hear about my dog who passes away, last week. He says, "I want to say thanks for your insight in your weekly podcast. I listen to several podcasts, weekly, and yours is the number one that I look forward to." David L., you're obviously a very smart guy – it just leaps off the page. He continues [laughs], "I only recently started to follow the market and my interest in investing, and I am so thankful that I have you and your guest knowledge and financial wisdom to glean from. I love how you openly admit when you made mistakes, and are always honest when listeners write in with criticism. David L."

That's by design, and I'm going to reiterate this every chance I get: I hate the way people on finance TV talk about everything like they knew it all along. They're bullish on the days when the market's going up, they're bearish on the days when it's going down, and nobody ever goes back and says, "Hey, you know something, we got something really wrong and we need to deal with it." So, we're going to do that on this podcast. Thank you, David L., for noticing.

Lori P. writes in, she says: "Longtime listener, here. Found myself nodding in agreement pretty much through the whole rant and interview with Jeff – " Jeff Ross. "Couldn't agree more about the absurd state of the markets, the good outlook for gold and miners bitcoin, and somewhat grim outlook for stock indexes, next 10 years or so. Until you started to talk about confirmation bias, which made me take a little pause and think through if this view is getting too much mainstream. Well, obviously, that can't be the case, now, considering the valuations and the crazy state we're in. But here is the question: eventually, if things play out like we think, and gold, bitcoin, and value stocks are outperforming like crazy, any thoughts how to measure if the initially non-consensus view is turning into the majority view with little upside? Bit of an oxymoron with value stocks that can be measured with all kinds of value metrics, but harder with gold and bitcoin. Cheers. Lori P."

You know, that is the last thing [laughs] I'm worried about, Lori, is when to call the top in all the stuff I want to own now. Howard Marks has a good slogan, he says, "Well-bought is half-sold." Meaning, if you do it right and don't overpay, it will not be difficult to figure out when to sell, right? If you're buying when things are really cheap, you'll know when they get really expensive. Here's the thing, Lori: it won't be a single moment, right? There will be no need to call a top at any given moment. But you may have, say, you make 10 times on some gold stock or other, and you want to, you know, buy a house or take a vacation, well, maybe you sell a little bit of that thing and pay for it. You see, there's no need to call that moment of the top. It's less of a worry than you think. But it's not a bad question [laughs], is it?

Last question, this week, is from Terry I. He says, "Longtime listener. Just wondering, again, about book value on companies today that the share price is way below their book values, like Cresy – " that's the symbol for Cresud – "for instance, has a current share price way below its book value. To me, it looks like a good value trade. Any thoughts? I realize this is not the only fundamental to look at, but a lot of companies' share prices are below this metric today. Oil tankers today, also, and some insurance companies. Thank you. Terry I."

Terry, I think your thinking is in a good place, here. I would look at book value as a screen for some of these hard asset plays that you're talking about. And for insurance companies, I think you should learn a little bit more about how they're valued. You know, you could get them on a value screen, and that could be, like, your initial screen that would get you interested in them, but you need to learn about – you need to measure float and – really, just float plus equity, right? The float is the investment, sort of, and the equity is the insurance underwriting capability. And you add that together and you get something like intrinsic value, and you really want to get them dirt-cheap, like, 50% off, that kind of thing.

But, yeah, in general, your thinking is good, oil tankers, big hard asset play. The oil tankers have been – well, the whole tanker complex has been a little disappointing, I think, because they've actually pushed back the requirements to outfit all the ships with scrubbers to keep down the level of pollution that they generate. So, that event was going to be the thing that kind of crimped the supply, and old tankers that it wasn't worth upgrading to the new equipment, right, they were going to instantly be gone from the supply. But now this is pushed out, I think, to – I think to 2022, maybe – I didn't get the exact data on that – it's 2021 or 2022, but you know, [laughs] it's not now – we thought it would've been by now.

I like the question, I like the way you're thinking. You've got to look into it a little deeper in general, but yeah, do book value screens and start from there. It's not a bad idea, at all. Thank you for that, Terry.

All right, that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. Do me a favor: subscribe to the show on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, help us grow, with a rate and a review. You can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram, and our handle is @investorhour. Also, follow us on Twitter, where our handle is @investor_hour. If you have a guest you want me to interview, just drop me a note at [email protected].

Until next week, I'm Dan Ferris. Thanks for listening.

[Music playing]

Outro: Thank you for listening to this episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to InvestorHour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail: [email protected].

This broadcast is for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

[Music playing]

[End of Audio]

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.