The Real Culprit Behind the Banking Crisis

In This Episode

This week, a Stansberry Investor Hour listener-favorite returns to the show... Kevin Duffy, editor of the Coffee Can Portfolio newsletter and hedge-fund manager, is back. And on his mind is the spectacular, near-overnight collapse of banks. But the foundation of this month's banking fiasco was laid years ago.

He explains how it all started... how Silicon Valley banks had risky loan books balanced with less-risky U.S. Treasurys... how banks' assets tripled during the two years of pandemic-driven government stimulus... and how the bond bubble burst and set off a chain reaction. "The problem showed up in the middle of 2022, but we're just now getting around to recognizing it," he says.

Kevin also shares that the root of the problem comes from the U.S.'s fractional-reserve banking system and reliance on the Federal Reserve and leverage. A simple way to understand the problems with today's banks is to list the characteristics of an ideal hedge fund. When that list is inverted, it describes a modern-day fractional-reserve bank. And as for the central bank, Kevin says it's more of a hindrance than a help...

These people [the Fed] are fighting the last war. They are basically designing a system that's going to prevent the previous bubble. But what they're not doing is essentially laying the groundwork for the next bubble and they're not anticipating that [...]

What's frustrating about this is that the solution to all this is very simple.

He argues that Americans would benefit most from a free-market system – one without the Fed. "Of course, you would take away all the problems supporting the system with central banking," Kevin says, "which is the inflation... the devaluation of our currency... the constant boom-and-bust cycles." He puts it simply:

The government, they're not just the lender of last resort. They're really the borrower of last resort [... ]

Part of what got us into this mess is the myth that the government can't default, the government is low risk or zero risk. The irony of this is that the longer we go on, the endgame of this is that the government is going to default.

Featured Guests

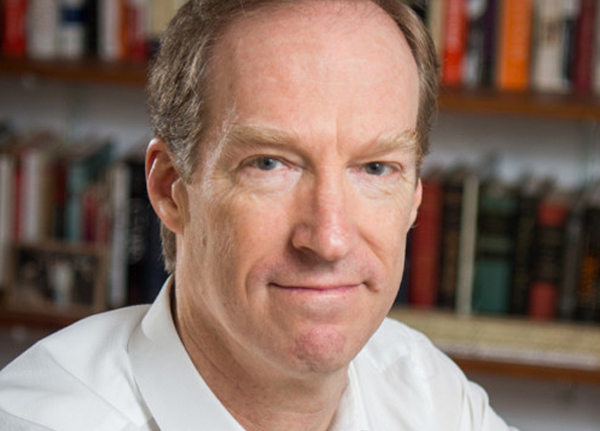

Kevin Duffy

Co-Founder of Bearing Asset Management

Kevin Duffy co-founded Bearing Asset Management in 2002 along with Bill Laggner. He and Laggner were vocal critics of the 2007 credit bubble, shorting many of its most aggressive players including Countrywide Financial, Fannie Mae, Citigroup, and Bear Stearns. Prior to Bearing, Duffy co-founded Houston-based Lighthouse Capital Management in 1988.

Transcript

Dan Ferris: Hello, and welcome to the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value and The Ferris Report, both published by Stansberry Research.

Corey McLaughlin: And I'm Corey McLaughlin, editor of the Stansberry Digest. Today, Dan interviews Kevin Duffy, co-founder of Bearing Asset Management.

Dan Ferris: And today we'll talk about bank failure. Lots of fun.

Corey McLaughlin: And remember, you can send us your feedback at [email protected] and tell us what's on your mind.

Dan Ferris: That and more right now on the Stansberry Investor Hour. So Corey, anything more fun than a good, old-fashioned bank failure? I don't know if there is.

Corey McLaughlin: Ooh, yeah. What a time.

Dan Ferris: I know.

Corey McLaughlin: A good, old-fashioned community bank run in Silicon Valley. I mean, who can make it up?

Dan Ferris: Yeah, I know. It's Silicon Valley of all places. All that money. All those billionaires and that's where we get the bank run. Great.

Corey McLaughlin: Well, you know, it makes sense in a way. Everybody's sitting in front of their computers or on their phones, you know, seeing all this news about this bank isn't solvent, which it hadn't been for several months. But all of a sudden it becomes a thing and a bank run happens. You know, everybody thinks they're so smart today, but the same things happen over and over for hundreds of years – well, you know, however long you want to say, whenever the first bank run happened. Yeah, I hate to say we expected some of these things, but this is what a Fed-tightening cycle has led to, this climate.

Dan Ferris: Right. You're never sure what's going to break first, but you know something's going to break, and it's obviously these banks. And people are finding out, you know, like you could do this to any bank in the country.

Corey McLaughlin: Right.

Dan Ferris: Really that's what scares me here, is that no bank has all the deposits available, like none, you know?

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. And that's what's happening. You know, that's why the contagion threat is so quick. You know, it's like, oh wait, people realize what's actually happening here?

Dan Ferris: Right. And this word confidence gets thrown around. Like President Biden, he had to use the word confidence. He had to say, you know, whatever it was he said on Tuesday morning. Have confidence. America's banking system is safe. I was like, oh my god, he said it out loud. [Laughs]

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, it's the same thing that Silicon Valley Bank CEOs said on the day when everybody was getting worried. Stay calm, which reminded me of the same thing the Chinese government said at the beginning of COVID, which was you Americans over there, don't panic. [Laughs]

Dan Ferris: Yeah, don't panic.

Corey McLaughlin: It's like, OK, well, and we see how all that turned out.

Dan Ferris: Yes. Methinks the lady doth protest too much.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. Anyway, I didn't mean to get too far off topic.

Dan Ferris: Well, it's true.

Corey McLaughlin: It's like you were saying, it's just we don't know where these weaknesses are going to come, but here they are.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. They have arrived. I don't want to talk about what the Fed's going to do next, because we beat the Fed horse to death last week, but it's interesting to contemplate exactly how all this happened. Just if there's a troubling, potentially systemic problem here, the piece that really bothers me the most is that Silicon Valley Bank's horrible run started on March 8 when they announced a couple of things. They announced that they had sold all their available for-sale securities, basically all their bonds, all their bonds and mortgage-backed securities at a $1.8 billion loss, and that then – they said, "Well, we're going to raise $1.8 billion-ish in debt and equity," or whatever, and then that announcement set off a $42 billion bank run.

I'm like, well, correct me if I'm wrong, but every bank in the country is holding this, like everybody's holding mortgage-backed securities and Treasury bonds, right? Which we know got whacked. You know, the Treasurys were down 30% in 2022, and if you just look at the mortgage-backed security ETF MBB, down 20-ish percent from its all-time high down about 17% last year. I mean, those are big moves for what are supposed to be like two of the absolute safest asset classes in the world. And all banks are holding them, right? So who else is having a problem here? It's worrisome, no? [Laughs]

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. No, it is, and that's what people – you mentioned confidence. It's, well, if this could happen there, why can't it happen in the bank I'm in? It's a very valid question. [Laughs] It really is. I mean, everything's a confidence game really. Somebody told me that a long time ago. You know, the markets are all a big confidence game, at least partially.

Dan Ferris: Sure.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, Silicon Valley Bank is not the only bank that did what it did and basically did some balance-sheet stuff where these securities ended up being kind of not hidden on the balance sheet but hard to find, that they were sitting on these billions of losses. You know, some analysts that followed it figured it out relatively quickly, but it's actually they were sitting on this like $16 billion in losses overall in these securities that you're talking about, and they just – the news they put out like, oh, you know, we can get past that. We got plenty of money on hand. Which honestly, if the bank run didn't happen, they would probably be OK in the long run just because they would still – you know, they'd be running their business and figure out a way to keep it going.

But because the bank run happened, they're not, which in a way this whole situation scares a lot of people, but in a way it shows you the power that real people still have in this world. You hate for there to be a bank run for it to happen, but these institutions are not infallible. They don't have to be there forever, you know? And it just reminds you about, I don't know, to me the humanity part of the markets, which a lot of times goes overlooked and people – like the professionals are talking about the numbers and earnings and whatnot.

Dan Ferris: Sure. Right, they're modeling.

Corey McLaughlin: When it comes down to it, yeah, what's everything there for, you know?

Dan Ferris: Right. They're modeling all this stuff like it's a machine, like it's a contained system like an engine or a machine or a washing machine or something. They know all the parts, they know how it all works, they know how fast it goes and where it's likely to break and all that stuff and how to fix it and all that, but it's not a machine. I keep saying humans are in markets the way fish are in water. You know, we didn't create markets. They just happened to us when we just allowed ourselves to get along with one another, you know, when we stopped beating each other over the head with rocks and when we stopped embargoing and declaring war and all that horrible stuff that doesn't work.

We just leave each other alone, trade happens, markets happen, and they happen to us the same way I think that water and wind and tides and waves and stuff happen to fish. We don't have control. The Fed doesn't have control. The banks sure as hell don't have control over anything, you know?

Corey McLaughlin: Right.

Dan Ferris: And, you know, that loss you just talked about, that wiped out their equity, $15 billion, $16 billion, whatever it was, and this can happen anywhere in the country. The thing is like a 10X-levered bank is like conservative. You know, that's the conservative one. [Laughs] I don't know. It is amazing that we don't get a lot more bank failures and that people do have the confidence that they do, I have to say. It's a modern miracle.

[Laughter]

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. Unfortunately, I think you're right. You know, and then maybe this won't be the last one of the next couple months or something, or maybe it will. You know, I also liken this to what happened, what was it, six months ago in the U.K. with – remember the gilts, the bonds over there?

Dan Ferris: Sure.

Corey McLaughlin: That pension crisis.

Dan Ferris: Oh, yeah.

Corey McLaughlin: It was similar and different in that it was tied to the Fed starting rate-hiking, which messed with the value of the euro and the bonds over in Europe, and that took down the value of the bonds there, which were tied to these leveraged pension funds, and then the central bank there stepped in and did a mini rescue.

Dan Ferris: Right. And around the same time, a similar event in Japan, bigger event in Japan, you know? $40-billion-plus event. They had to intervene to save the freaking currency.

Corey McLaughlin: Right. So essentially, the same thing is happening here. It's more of an effect of the lag of the U.S. interest rates. These decisions made by Silicon Valley Bank were 18 months ago that ultimately caught up to them now because they bought these long-term Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities before the rate-hike cycle. When the rates went up, they turned to losses. My point is, maybe more of this happens but maybe not too.

Either way, the Fed's already stepped in and intervened again, which I saw a couple nights ago the Fed balance sheet, right? The chart of the Fed balance sheet and the trimming that had been happening over the past half a year or so, and what they did with this bank loan – I forgot the acronym, whatever they called it – to prop up these banks, cut out half the balance-sheet reduction and all of the balance-sheet reduction that happened in the past four months I think it was. So, you know, then you have to listen to the Fed say, "Oh, but we care about inflation and we're trimming the balance sheet as part of that and we're raising interest rates as part of that, but oh wait, when something happens with a Silicon Valley Bank and a couple others, you know, we can deal with a little higher inflation," essentially is what they're saying. They're not ever going to say that.

Dan Ferris: Exactly.

Corey McLaughlin: But the end game for it is we'll intervene at the expense of something, and that something is probably going to be more inflation.

Dan Ferris: Exactly more inflation. Yeah. This is the epic battle. I wrote about this in The Ferris Report. I forget what issue. There's only a few of them because it's a brand-new publication, so maybe second or third issue. But I was writing about the thing called the "Dollar Milkshake Theory." We talked with Brent Johnson about that.

It's an epic battle. It's banks and bond markets on one side of the ; and currency is on the other, right? So you're either saving the banks or you're saving the currency, and ultimately, as you're pointing out, the currency always has to kind of give up a little bit so we can save the banks and bond markets, and that's what happened in the gilt crisis, that's what happened in that Japan crisis around the same time, last September. Same thing.

You're right. It's all the same. It's a battle between the currency on one side and the banks and bonds on the other, and they always choose to save the banks and bonds.

Corey McLaughlin: Right. The currency loses, yeah.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Yes.

Corey McLaughlin: And an important difference this time is, you know, for the last how many years interest rates were going down and were near zero, but now they're at a trend – you know, they're above the previous cycle's highs already. So we're in this environment, I think, where rates ultimately keep going higher, and in the past, the central banks would come in and cut rates, not worry about inflation going higher. Now if they cut rates, inflation is still above the hypothetical 2% goal, so you have to – it's not as simple as just cutting rates and saying, oh, we're coming to the rescue because of higher inflation. So it is different. I hate to say that, but we're –

Dan Ferris: It's different this time.

Corey McLaughlin: You know, when you talk about flipping the markets on their head the last 20 years or 40 years, whatever you want to do it, this is one of the big consequences. Like the central banks, they can only probably make things worse at this point. I don't know what they're going to do. I hate to laugh during that, but this isn't like where '08 where they could step in and just lower rates and flood – they can lower rates, but there's going to be an expense here. It's going to be more persistent inflation, I think.

Dan Ferris: Right. The problem here is like these forces are epic and they're so big that really you almost can't stand back far enough to figure out what to do about them. I wasn't short Silicon Valley Bank, I wasn't short Silvergate. I wanted to be short Silvergate a while ago, but I don't like shorting in general because it's really difficult, and I think there's still a lot of speculative juice out in the market, remarkably. So what do you do? It's hard, it's hard.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: I think my basic prescription of prepare, don't predict, and then hold plenty of cash, hold gold, buy good cash flowing businesses, don't overpay. All that stuff I've been saying a million times, it probably sounds like I'm throwing my hands up, but I honestly believe it's prudent. But there is a lot of uncertainty and a lot of risk to think about. It's a rough time. It is a rough time.

We talked with Cullen Roche. Do you remember we talked with Cullen Roche and he was talking about the slow grind? I think the slow grind is here. The grinding has begun.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah, I'm with you. Yeah, I hate to sound too doom and gloomy, you know, because you kind of have to live your life and move ahead, and if anything, you know, I think from a stock, bond, investment perspective, if this causes the Fed to pause the rate hikes at the next meeting or say they're going to pause them or something like that, stocks are going to like that, I think. Or the opposite could happen and they're like, oh no, this means something's wrong. Because I keep thinking also – I'm contradicting myself as I speak here, but I keep thinking about how every bear market since 1955 hasn't ended until the Fed starts cutting rates.

They haven't paused yet. I mean, they might. It might be this month, it might be next month, and then, OK, could stocks enjoy a nice little run again? Sure. Then we're into the real lag effects of the interest rates and the recession, if you think a recession is coming. Then they cut rates, and like I was talking about earlier, either is inflation still a huge problem at that point or not? That'll play into that.

Dan Ferris: Yes, it is, it is, and I'll tell you why. Because that recession doesn't solve – and the rate cutting and the recession and whatever ensues there does not solve the supply issue, right?

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: We're still coming out of a pandemic. We still have supply-chain issues, and that's why the Fed is like trying to crush demand with rate hikes, right? They're just trying to crush demand. They're not doing anything about supply. They're not doing anything to encourage the production of additional goods and services to meet this growing demand, right?

So what happens if we get a recession? Does that incentivize anybody to do that? No, it doesn't. So we come out of that – and this happened – like the '70s inflationary decade was split in half by a recession. Same thing. I think that paradigm is – you know, this is not the '70s, but that part of it, that works for me. That makes total sense.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. And to continue the thought there on if we're going to see a Fed pause now, I think generally speaking that would be good for bond prices because yields are probably going to come down and gold too, I think. I think a lot of stuff's lining up for gold. I think that would be welcome news to a lot of people. If we're talking about higher than expected inflation and slowing down of the economy, to me gold makes a lot of sense for a lot of different reasons.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Gold's less than $50 from $2,000 as we speak.

Corey McLaughlin: Oh, all right. Yeah. I know it's been 6% since all this banking stuff started, so yeah, I think if you've been waiting around for gold to take off, I think all this chaos is actually good news for that, which is why you want to own it in the first place.

Dan Ferris: Right. It just reminds me of Charlie Munger. Every time he talks about gold, he said, "You'd have to be insane to want gold prices to go up, because when they go up everything else is going to hell."

[Laughter]

Corey McLaughlin: Yep.

Dan Ferris: So I have to point out – I hate to do this because I'm not a technical analyst, but starting maybe February of this year, a little over a month ago, like early February, late January, there's this formation in gold that we call a cup and handle. I'm not a technical analyst but I know people who have traded this formation successfully, repeatedly. And so right now we're forming like a full cup, and then you get this little handle that corrects on the other side of it, so maybe gold retreats back down to around $1,900 or so, and then that's your moment. If it's going to fly, that's the moment to get in. And even now, if you can tolerate, what, you know, $50 when we're at $1,953 or $1,954 right at this moment, what's $50? Who cares?

You can start buying now. But this moment is lining up, and the action really since November has been pretty great. Gold bottomed in September around $1,600 or so, just looking at a Bloomberg chart here, and now we're at $1,950? That's a pretty decent move. So yeah, I'm ready to buy me some more gold, man.

Corey McLaughlin: I've been doing it the last couple months. I've been kind of dollar-cost averaging in. I was very pleased this week when I saw the results of that.

Dan Ferris: It's crazy.

Corey McLaughlin: That's why you do that, you know?

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Corey McLaughlin: You don't know the exact timing of these things, but if you spread it out enough you can enjoy the benefits.

Dan Ferris: Charlie's right, it's crazy. It's like I was so pleased when the banks failed and my gold went up, you know? [Laughs] But that's the way it is. You're pleased to have gold. You're not pleased that other people are suffering.

Corey McLaughlin: Correct.

Dan Ferris: However, there is a bit of schadenfreude, I must admit, when people do crazy things with cheap money. I mean, that's the ultimate problem. Well, fractional reserve banking plus cheap money. What a horrible combination. We knew everybody who was long all this crazy, garbagy, cash-burning tech stuff, which Silicon Valley Bank essentially was by taking both their loans and their deposits.

You know, it wasn't going to turn out good for anybody who was long this garbage, you know? ARK Innovations down 70%. I mean, come on. It was all predetermined as soon as they were all in at the top.

Corey McLaughlin: Correct. Yeah. There are certain people you feel for. There's other people you don't.

[Laughter]

I would say the CEO of the bank of Silicon Valley Bank, who was on the San Francisco Fed Regional Board, I mean, what are we talking about here?

Dan Ferris: Right.

Corey McLaughlin: [Laughs] I could go on for a long time about all the conflicts of interest and all that stuff.

Dan Ferris: Exactly.

Corey McLaughlin: And then who gets bailed out and who doesn't? That's a whole other debate and a whole other talk.

Dan Ferris: That is a whole other thing, but just the sheer level of incompetence, like if bank management teams don't know how to handle a rising interest rate environment, who does, you know? This is literally their job, was to navigate this environment. You had one job, right? They completely botched it up. They did the exact wrong thing at the exact wrong time.

Corey McLaughlin: Yeah. Higher rates should be good for banks because they're able to make more on the shorter end. [Laughs] I don't know. I'm not a banker. Never wanted to be.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, me neither.

Corey McLaughlin: But, you know, here I am talking about bank failures.

Dan Ferris: All right. Let's talk with our guest about banks and bank failures. I know he's quite a critic of the banking system so I can't wait to see what he tells us. His name is Kevin Duffy. He's a friend of mine. We've had him on the show a couple of times. Let's do it, let's talk with Kevin Duffy right now.

If you're holding out hope for a bull market, then please pay close attention. According to legendary investor Marc Chaikin, who Jim Cramer famously said he'd never bet against, you need to prepare for the next wave of volatility to hit U.S. stocks. Marc's prediction is based on an indicator that has only triggered a handful of times in the last 72 years with a 100% success rate for predicting where stocks will go next. Now the man who's just spotted it is sounding the alarm.

During Marc's 50-year career, he's worked alongside some of the biggest investors in history, including Paul Tudor Jones and Michael Steinhardt. In fact, Marc invented one of Wall Street's most popular indicators for picking stocks, still used by hedge funds, banks and brokerage sites, and today found in every Bloomberg terminal on the planet. Now Marc's inviting you to join him as he explains exactly what the next wave of volatility will look like and where it will send stocks in the coming weeks. He's even sharing one of his favorite ideas free for those who tune in.

He says this idea could create bigger gains than anything he's used his Power Gauge system for until now by turning the coming market volatility to your advantage. And you don't have to wait until March 28 to get started. For a sneak peek of Marc's big reveal, go to ChaikinEvent23.com. That's C-H-A-I-K-I-N Event23.com.

All right. It's time for our interview once again. Today's guest is my friend and previous podcast guest, Kevin Duffy. You can find him on Twitter, @KevinDuffy1929, and he's the author of a really good newsletter to which I do subscribe called the Coffee Can Portfolio. Kevin, thanks for coming back to talk with us again.

Kevin Duffy: Dan, thanks for having me back on.

Dan Ferris: So let's not beat around the bush here. Folks have gotten to know you in two previous episodes, so they can listen to those if they want some background, but we've got to dive into this SVB thing, Silicon Valley Bank, because it's serious business. I know what I think about it, but I want to know what you think are the key takeaways from this.

Kevin Duffy: Well, you know, you don't know where to begin with this.

Dan Ferris: Right.

Kevin Duffy: But I actually put together some statistics on the growth of bank assets leading up to the COVID response, the massive stimulus. So you had from the end of 2014 to the end of 2019, commercial bank assets were up 34%. Then the Fed came in and sprayed money everywhere. Now during that time, the Fed's balance sheet had actually grown about 4%, which is a little surprising to me that bank assets grew faster than the Fed's balance sheet.

But anyway, the Fed's balance sheet grew by 112% in the two years from the end of 2019 to the end of 2021, and commercial bank deposits went up 82%. So in the previous period, of course we have this boom in Silicon Valley and Silicon Valley Bank's assets grew up to COVID 82% over that time, so well above normal. During the two years of the COVID stimulus, they tripled. So you had this just massive boom in assets.

So that's part of it. So the bank is basically making loans to private equity, to venture capital, so they have a risky loan book. What they're doing is basically balancing that with Treasury securities, and in their case, more importantly, residential mortgage-backed securities. So as long as these securities were either government securities or they were backed by government guarantees in the Basel III requirements in terms of how they calculate capital and they're risk-weighted assets, they got a zero weighting, OK?

So they were doing everything according to the book to balance this risky loan book with less risky assets. I think the bottom line is that those assets that a bond – you could have a AAA credit, it could be rock solid, and we could have a debate about whether the government is a AAA credit or not, but the problem is that a bond, if the yield goes to zero or gets very low, then all of a sudden you have a price risk. This was not in anybody's models. This was not on the radar screen.

So when the bond bubble burst in 2022, of course, the part of the boat that was supposed to be ballast now sprung a leak. Making things even worse, a lot of those securities were held to maturity, so they were kept off the bank's balance sheets in terms of these risk parameters, these capital ratios. So really the problem showed up in the middle of 2022, but we're just now getting around to recognizing it.

Dan Ferris: Right. So 2022, my take on this is that cheap money killed Silicon Valley Bank because they loaded up on treasuries and MBS, mortgage-backed securities, right at fairly near the top, right? The real top was in 2022, but they really loaded up throughout that period, actually. Like you say, it's a two-year period, end of 2019 to the end of 2021. Assets tripled, deposits tripled, and I think per-share earnings were up from 21 to 33 per share.

It was a huge boom. All the metrics just went off the charts and they were geniuses, right? But then cheap money got them. And my view is like the cheap money had them as soon as they took it on. As soon as they succumbed to it and tripled all these assets under 0% interest rates, they were doomed one way or another. Maybe not doomed to fail, but doomed to have a really bad time.

And when did they fail? Well, they failed when they sold all their available for sale securities, all the cheap money, and lost $1.8 billion. Oops. And then they announced they had to raise $1.8 billion. Oops. And then the run happened. They lost $42 billion of deposits in a week, you know? Cheap money killed them, in my opinion.

Kevin Duffy: Yeah. I think that was part of what killed them, but I think the bigger source of the problem here is fractional reserve banking itself. That to me is the root of the problem, and the root of the problem here –

Dan Ferris: Absolutely correct, yeah.

Kevin Duffy: And the root of the problem here is leverage. I started thinking about this as a hedge fund. You could think about a bank as a hedge fund, and you could think about, OK, you want to invest in a hedge fund. What are the qualities that you're looking for in a good hedge fund? So I wrote these down. Well, one is you want contrarians, you want people that kind of think independently, out of the box.

You want them to be unconstrained, to be able to go where the best opportunities are, independent of government narratives and independent thinkers. You don't want leverage. You don't want a whole lot of leverage in a hedge fund. In fact, if anything, you'd like the hedge fund to maybe even hedge. You want patient capital. You want investors. This is the secret of Seth Klarman, patient capital.

You want conservative pricing, you want tight risk controls, and you'd really like to have skin in the game. You'd like the people running the money to have skin in the game. OK, that's kind of the ideal hedge fund. Now let's invert that, all right? And I think if we invert that, what we see is a classic modern day fractional reserve bank.

What we have, instead of contrarians, is conformists. We have people that are very much constrained by politics, by regulation. They become very dependent on the government and even more so with the great financial crisis in 2008.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Pure status quo pursuers.

Kevin Duffy: Absolutely.

Dan Ferris: Pure pro cyclical status quo. Yep.

Kevin Duffy: Absolutely. And so as a result, these nonconformist, status quo seekers have a knack for ending up piling into the bubble assets at the time. You also have they're highly leveraged. So you look at something like Silicon Valley Bank, their total assets to shareholder equity. Now this is the false shareholder equity. Forget about the unrealized losses.

But it was 13.5 times. Now you say, OK, JPMorgan is a fortress balance sheet. Well, it's 15 times. You know, so a good bank might be 10 times. Highly leveraged. And maybe some of these banks are hedged, but apparently in the case of Silicon Valley Bank it wasn't.

You have very subjective pricing of these illiquid assets. That's a problem. You have these loose risk controls where you're not marking to market the securities, even the ones that are liquid, OK? And then what you really have, instead of having patient capital, you have fickle capital. So you have these demand deposits and these people can just – you know, if they catch wind of all of the leverage in the system at the bank, they pull their assets.

And then, of course, you have basically little skin in the game, so you have banks that are playing with other people's money and it's heads they win and tails they get bailed out and the losses are socialized.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, losses are socialized. And that, of course, the socialization of losses is a function of the other thing that's wrong with the banking system, which is the existence of the Federal Reserve, right?

Kevin Duffy: Right.

Dan Ferris: We had a dozen events in the 19th century, early 20th century in the banking world where, you know, several banks went under and then the world went on its merry way, and then the Fed comes in and systematizes risk and spreads it through the entire system, basically the Typhoid Mary of banking in U.S. history, and then we get the Great Depression.

Kevin Duffy: And the thing about the Fed, I mean if you go back to fractional reserve banking and you think about this, you know, I think of it is as just a hedge fund, and I have no problem with people – hey, you want to run a hedge fund? That's fine. But I think that what would happen in a free market is that that system would collapse, OK?

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Kevin Duffy: So the problem is it cannot exist without some kind of support, and that support is whether it be deposit insurance or whether it be the central bank, but the central bank has to be there in order to keep this whole thing afloat. That is the problem.

Dan Ferris: Right. You have to have a lender of last resort and you have to have deposit insurance and all the rest of it. That's right.

Kevin Duffy: Exactly. Yeah. So the problem is that every time we get a crisis, the government comes in, supports the whole system – what does it have to do? It has to expand their balance sheet, print money, OK?

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Kevin Duffy: And then they design – this is what happened after the 2008 crisis, is they come up with a design basically to fight the last war. We're going to prevent the last bubble. And the problem is that these people are fighting the last war, so they are basically designing a system that's going to prevent the previous bubble. But what they're not doing is – essentially they're laying the groundwork for the next bubble and they're not anticipating that. Then life finds a way.

Water runs downhill. It finds the cracks in the system. And that's what's going on right now. This is all playing out.

Dan Ferris: It's insidious and it just goes on and on and on. There's never a learning moment at the level of the Federal Reserve or banking regulators or government or anything. It's just endless narrative seizing and narrative exploiting. Nobody ever says, you know what? – and then basically repeats what you just said. Nobody ever says that. [Laughs] Only people like you say it.

Kevin Duffy: You know, what's frustrating about this is that the solution to all this is very simple. The solution is that you should really have warehousing. And if people want to have their "rainy day" fund, meeting payroll, all these functions where you don't want to put any money at risk at all, that money should be warehoused. So if Vanguard can run an index fund at 3 or 4 basis points, why can't a bank run a warehouse for cash that would charge very little, OK? And have that totally separate from loan banking.

It would be just another investment that people would make. You know, we want to invest in mortgages, we want to invest in home loans or commercial loans or whatever, and these deposits, they would be investments. They would be gated, they would be in illiquid investments. People would understand that your money is at risk, you're going to be compensated for that, and I think it would solve – of course, with such a system, you wouldn't need a central bank. So you would not have all the problems that come with the central bank.

Dan Ferris: Right. And how would people behave, Kevin, if they knew that there was no lender of last resort and no deposit insurance? Would they behave differently? I think they probably would. They're constantly being told this story that you'll be taken care, the deposits are insured, there's a lender of last resort, the system can't go down, etc. You know, we saved it once and we'll save it again.

It's too big to fail and we can print what we need to print. If there was none of that, I think our culture would be different. Our whole culture would be different.

Kevin Duffy: Yeah, absolutely. It would be very different. Behavior would change on both sides. People would know that they're taking risk, they would want to participate in that, participate in the rewards. It would raise a higher bar on investments. There would be a real cost of capital. So that capital would be allocated differently.

And what it would mean is that – I looked at JPMorgan, OK? Just to get a sense for the amount of leverage. If you look at their leverage, it's like I said 15 to 1. Their return on assets last year was 1%, OK? If you compare that to Walmart, Walmart is levered five to one, OK? Their return on assets was 5%.

So what we're doing here is we're basically funneling money into allocators of capital that are not very good at it, OK? The money is not finding its way into the best allocators of capital. I think if we had really a free-market system in money and banking and investing that you would have a much better allocation of resources, and I think that this whole model, this whole banking model would basically – it wouldn't disappear, but it would be forced to compete with other models, and I think you would just have a much greater, much better allocation of resources, and of course you would take away all the problems with supporting the system with central banking, which is the inflation, you know, the devaluation of our currency, the constant boom and bust cycles that we get with it.

Dan Ferris: Sign me up. [Laughs] It sounds good to me. I think it's frustrating to people like you and I because we're of one mind on this issue, and yet the learning that seems to be happening in the halls of power where these things can be influenced and put into practice seems to be in the opposite direction. They seem to be saying, well, that worked out great for me because I wasn't at risk. It was all the depositors and everybody else and I got bailed out and I still got a bonus. The learning seems to be going in the wrong direction, I think. It's very frustrating.

Kevin Duffy: Well, the problem with the system is that there are, as with all of these schemes, winners and losers. The people that benefit are in the government, and there's a very symbiotic relationship between the banking system and the government. And what's happened over time – it's always been like this, but over time as you've had one crisis and the next crisis is bigger than the previous crisis, and what happens is that the government is basically taking over the borrowing function. So what you're seeing is a crowding out.

The private sector through the banking system, loans are not being made as much to the private sector and the government is basically – they're not just the lender of last resort, they're really the borrower of last resort. So this is what's happening over time, and what I believe is that the government is not a productive asset. This is another part of the misallocation of capital that's going on. What we're doing is we keep on funneling money through this system into the government, and right now nobody's thinking about – part of what got us into this mess is the myth that the government can't default or the government is low risk or zero risk, and what's happening – you know, the irony of this is that the longer we go on, the end game of this is that the government is going to default.

We've got $31 trillion in debt, not counting all the unfunded liabilities, and Biden just proposed, I believe, a $6 trillion budget. So these people don't realize that we've reached an inflection point with the everything bubble. We're two years past that. I think bubbles – you and I agree on this – this is the greatest bubble known to mankind and it's not over yet. It's in the process of unwinding. I also believe that bubbles mark major inflection points. So if we look at bubbles, bubbles always have a false belief, and I belief that this bubble, the false belief is government as universal problem solver.

I believe that's what is driving this. So where this all leads is I think we've seen a peak in the centralization of government. It's a 234-year trend in the United States, and I think the everything bubble marks the end of that trend. Now we're in the extremely early stages of all of this, of course, so people are not recognizing – we're in the denial stage. They don't see that a change has happened. The politicians will be the last ones to get the memo that things have changed.

They're all behaving as if it's business as usual. I don't think it is. I think we're going into a very different period where this stuff is coming to an end. The government is going to have to make some choices. You know, they're going to have to live with constraints. I think as investors we have to be aware of this, try to navigate through this, what should be ultimately a really good thing.

Dan Ferris: Ultimately, yeah. Between now and ultimately is a lot of pain. So you started getting at a really good point though, and I would say it this way. The Federal Reserve, and even the government itself, they start out as this kind of utility function. You know, they're in the background. They're an umpire. They do a few important things and they're not supposed to do a whole lot else.

But the fact that it's centralized makes it too attractive and it gets abused and it takes over. And as you say, it's not just the lender of last resort. It becomes the borrower of last resort. And instead of being the umpire, the umpire takes over the game. And this is Jim Grant from Grant's Interest Rate Observer, right? He says this is ridiculous.

With the Federal Reserve, it's like having the umpire of the baseball game on the cover of the sports magazine instead of the big star who's got all this great skill at playing baseball, right? So that is what has happened. And I agree, at some point it comes to a crisis where everybody realizes, ooh, this can be broken. It is breakable. This lender of last resort is not unbreakable.

The simple existence of it as a central power is a magnet. It's a magnet for everything that would otherwise fail, like government itself. It just attracts all the power hungry and all the schemes that would never make it in a free market, so therefore sowing the seeds. Its centralization sows the seeds of its undoing, proving that that is the main problem with it.

Kevin Duffy: Yeah. Absolutely. And I think this is the whole point, is that – and this is maybe a controversial thing to say, but I do believe that replacing the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution kind of set this country on the path toward centralization, and there are many steps along the way – Civil War, Federal Reserve Act, you know, on and on and on – but that trend went on for 232 years and I think it hit a wall two years ago. So we're now in the process of – and we've got decentralization going on as well. You know, you see it with the Internet.

You see it with remote work. You know, we're doing this interview remotely right now. So you've got all these forces of decentralization that are really invigorated right now and maybe even got a boost through COVID. So you've got that on one side, you know, those forces that are just building and building and building, and then you've got this long trend of centralization that is basically running on fumes. And I think the people that are in that camp, it's the extrapolation game, right?

I think there's a chapter in Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Taleb. He calls it survival of the least fit, and it's all about – it's an evolution that what happens when you have these long, benign periods is that creatures that survive and thrive during that period, they become more and more specialized and they become more fragile to the new environment. And so I think this is kind of where we're at. We've got a lot of these creatures out there, whether they're bankers or whether they're politicians or venture capitalists or academics or whatever, they're all creatures of this very benign environment, whether you want to describe an environment of 232 years or maybe the last 10 or 15 years with zero interest rate policy.

But what's happened right now is we have a change. We have the C change that's taking place. It's very early. So those people are – of course they don't want this to change. They love the old environment, OK? They're not prepared for the new environment, and so they're telling us, hey, don't worry, we've got it – hey, the banking system is sound, everything is under control, don't worry about it.

Dan Ferris: Warren Buffett, don't bet against America, right?

Kevin Duffy: Exactly. And this is a great time – I think first of all it's a great time to be a contrarian, you know, watch this all play out. So there is a chapter in Nassim Taleb's book Fooled by Randomness, and it's called "Survival of the Least Fit," and it describes evolution where you have a benign environment, and the creatures that survive and thrive in that environment, you know, they evolve and they become more and more specialized. You can think about the Galapagos Islands and the finches growing beaks that allow them to dig deeper into branches and look for ants or whatever. The problem is that when the environment changes, especially when it becomes a hostile environment, that these animals, these creatures are very fragile to this new environment, to the changing environment, OK?

I think this really describes what is happening today, is that we've got all these kinds of creatures that have thrived in this very benign environment, you know, whether it be Zurich or the last 15 years since the 2008 crisis or whether it be the last 232 years with the centralization of power. These people – you know, I believe that we're at this sea change and they're living in the past. You know, they don't want this – they love the benign environment. So you can think about it in terms of maybe your financial adviser.

Is he a creature of the past? And the problem is that these people will be the least prepared for the new environment. So these are the people right now that are saying don't worry, the system is sound, you know, don't worry, we've got things under control. These are the same people that have been running things, and the problem is they're going to be running things right into the ground and making things worse.

Dan Ferris: This, Kevin, reminds me of a blog post by Marc Andreessen, the billionaire and entrepreneur and venture-capital guy actually, and on this blog post he was saying – what I took from it was all the stuff that the government is heavily regulating and heavily involved in, like education and health care, he named those, he says the price just keeps going up and up and up. Health care is a real mystery because it's so technology driven and the price keeps going up and up and up. And yet, you know, there's all kinds of stuff like TVs and computers and all this other technology-driven stuff, the price just keeps going down and down and down.

He says this is the dividing line, and I feel like you're describing that. You're describing all of this stuff that the centralized power takes over. The price goes up and up and up and, you know, that's not good for anybody. It's not even good for them in the end. Then it fails. But the rest of this stuff, like I have a more powerful computer in my pocket than stuff that used to fill rooms decades ago, so effectively the price has gone down and down and down. Markets work I guess is the lesson, right?

Kevin Duffy: Yeah. Markets work, and I just think you have these two forces that are taking place right now.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, it's epic.

Kevin Duffy: What's happening is you are corrupting these institutions and destroying them, but at the same time, and it's like the forest fire analogy where everything – you have this old forest and it burns, but at the same time – so that's, of course, the downside, but the upside is that you have all the green shoots and it brings about this – you know, it clears out the dead wood and it creates all the sunlight and the nutrients and everything for this new growth to take place. So I think we have to balance what's going on, and it's just reality. You know, this is the world that we live in. You try to get as far away from these institutions that are failing and try to gravitate toward the positive things that are going on.

I think this is what's very exciting, is that you have these two epic forces, you know, one is dying and another is just getting stronger and stronger, this force is decentralization and all the things that you talked about where prices are coming down. You look at what's going on with genomic sequencing. I was reading about – I forget the name of the company, but the price is coming down to like a couple hundred dollars to sequence the human genome, and all babies born are now going to be sequenced. If we go back to 2000, I think the first time they did it, it cost something like $1 billion.

That's deflation. So it's kind of interesting how you look at the technology-driven deflation that's taking place in the one camp, and then you have this other side that's basically trying to inflation everything and they're trying to say that there's something wrong with deflation. Well, there's nothing wrong with a natural deflation. Even a bubble bursting type of deflation is a good thing, in my opinion.

So what we're seeing is two entirely different worlds right now, these forces that are in an epic battle, and what I see is just the old is dying and the new is taking over, and this is going to provide this incredible renaissance. But as you said, the transition period is going to be painful, it's going to be bumpy. For those people that are living in the past and unprepared, it's going to be especially painful. I think if you understand what's taking place you can try to protect yourself.

Dan Ferris: All right. I actually think this is a perfect moment to address my final question, because that was a beautiful summation right there. The final question. You've answered it twice before. It's the same for every guest no matter what the topic. And that is if you could leave our listener with a single thought today, whether it's financial or economic or just general wisdom, whatever you like, and even if you've already said it, feel free to repeat it, if you could leave them with one thought today, what would it be?

Kevin Duffy: OK, sure. I think we're at a major inflection point. I think we're very early, and it's going to be bumpy. So the first thing, my advice to people always is grab the oxygen mask. You know, take care of yourself. You're not going to be able to help anybody else unless you do that.

The second thing is, you know, kind of step back and look at this maybe as a good citizen or somebody who wants to really understand the root of the problem and change this. You know, understand that we can change the system. We only need about 10% is really passionate people, if they understood fractional reserve banking and central banking and understood the problems with this, the inherent design flaw of this system, I think we could end this by next Tuesday. So my advice would simply be get up the learning curve.

I would recommend people go to Mises.org, the Mises Institute's website. They're very good on central banking and fractional reserve banking. And also read Murray Rothbard. He's the foremost, was the foremost critic of central banking. There's a couple of good books that I could recommend, What Has Government Done to Our Money, which he wrote in 1963, and then before he passed away in 1965 he wrote The Case Against the Fed, which really describes this idea of warehousing and loan banking and how it all works.

Dan Ferris: Excellent, excellent. Thanks for that, and thanks for coming back and talking with us.

Kevin Duffy: Thanks. Thanks for having me back on.

Dan Ferris: Yeah, you bet.

Kevin Duffy: It's going to get more interesting. I can guarantee that. [Laughs]

Dan Ferris: Many mainstream analysts are predicting that stocks will recover soon, but I say we'll instead witness a cash frenzy unlike we've experienced in 21 years before stocks recover, and I'm urging Americans not to buy a single stock until they see it. I predicted the Lehman Brothers crash in 2008 and I called the top of the Nasdaq in 2021, but this is the No. 1 most important thing to pay attention to for 2023. And I'm not talking about another market crash or politics or inflation or any of these other things. As all this unfolds, the financial consequences of what I'm talking about could last for several decades if you don't understand what's happening.

There will be winners and losers, and now is the time to decide which one you'll be. This is why I strongly encourage you to read about my warning totally free today. It's all spelled out in a free report we've put together. Get the facts yourself. Go to www.stockdeadzone.com to get your free copy of this report. You can learn about how to get my four steps to prepare for what's coming. Again, that's www.stockdeadzone for a free copy of this new report.

I'm really glad that we had Kevin Duffy on because he's got his own particular way of seeing the world, and it's from obviously a very deep belief in the power of free markets, which I also have so I agree with a lot of what he said. Most of it, I would say. So we got to hear, you know, his take on really the underlying cause of the Silicon Valley and Signature Bank and Silvergate and all the rest of it, of these bank failures, which I couldn't disagree. I can't disagree that it's the essence of the fractional reserve system.

You know, Silicon Valley Bank had this $42 billion run on deposits in one week and then they had to shut it down. This can happen to any bank in the country. People don't realize this. No bank can withstand a run on deposits. The safest bank in the country can't withstand a run on deposits. I mean, you heard Kevin talking about it.

They're all leveraged. A more conservative bank is only levered 10 times, you know? [Laughs] So it's crazy the way this system works. It's a pure confidence game, and people lose confidence and they take their money out, the bank fails. It's just like that. And it can happen to the whole system, and we're kind of lucky that it hasn't happened so far.

Great stuff. I love the way Kevin thinks, and I follow him on Twitter. He's a very wise fellow and a great investor too. Great to talk with him.

Well, that's another interview, and that's another episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. We do provide a transcript for every episode. Just go to www.investorhour.com. Click on the episode you want, scroll all the way down, click on the word "transcript," and enjoy.

If you liked this episode and know anybody else who might like it, tell them to check it out on their podcast app or at InvestorHour.com.

Do me a favor, too... Subscribe to the show in iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, help us grow with a rate and a review. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram – our handle is @investorhour. On Twitter, our handle is @investor_hour.

If you have a guest you want us to interview, drop us a note at [email protected] or call our listener feedback line at 800-381-2357. Tell us what's on your mind and hear your voice on the show. For my co-host Corey McLaughlin, till next week, I'm Dan Ferris. Thanks for listening.

Announcer: Thank you for listening to this episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. To access today's notes and receive notice of upcoming episodes, go to InvestorHour.com and enter your e-mail. Have a question for Dan? Send him an e-mail at [email protected].

This broadcast is for entertainment purposes only and should not be considered personalized investment advice. Trading stocks and all other financial instruments involves risk. You should not make any investment decision based solely on what you hear. Stansberry Investor Hour is produced by Stansberry Research and is copyrighted by the Stansberry Radio Network.

Opinions expressed on this program are solely those of the contributor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Stansberry Research, its parent company, or affiliates. You should not treat any opinion expressed on this program as a specific inducement to make a particular investment or follow a particular strategy but only as an expression of opinion. Neither Stansberry Research nor its parent company or affiliates warrant the completeness or accuracy of the information expressed on this program and it should not be relied upon as such. Stansberry Research, its affiliates, and subsidiaries are not under any obligation to update or correct any information provided on the program. The statements and opinions expressed on this program are subject to change without notice. No part of the contributor's compensation from Stansberry Research is related to the specific opinions they express.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Stansberry Research does not guarantee any specific outcome or profit. You should be aware of the real risk of loss in following any strategy or investment discussed on this program. Strategies or investments discussed may fluctuate in price or value. Investors may get back less than invested. Investments or strategies mentioned on this program may not be suitable for you. This material does not take into account your particular investment objectives, financial situation, or needs, and is not intended as a recommendation that is appropriate for you. You must make an independent decision regarding investments or strategies mentioned on this program. Before acting on information on the program, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and strongly consider seeking advice from your own financial or investment adviser.

Get the Investor Hour podcast delivered to your inbox

Subscribe for FREE. Get the Stansberry Investor Hour podcast delivered straight to your inbox.