Investor Hour's Top Interviews of the Year

In This Episode

As 2020 draws to a close, it’s time to look back at an incredible year of Stansberry Investor Hour interviews.

We’re not just doing a simple year in review of the markets though.

Instead, Dan and his crew took the time to gather up the very best clips from the most important episodes of Stansberry Investor Hour – ones that he says could have a profound impact on your wealth.

It’s an episode jam-packed with valuable insights from some of the biggest legends in the investing world.

Dan recaps some amazing lessons he’s found from some influential thinkers like Jack Schwager (episode 183), Annie Duke (episode 181), Raoul Pal (episode 140), Bill Browder (episode 153), John Stossel (episode 159), and many more…

Plus, Dan takes a look back at some of the predictions made and how their advice would have panned out if you followed it over the year.

It’s the one episode this year you DEFINITELY don’t want to miss.

Listen to Dan’s most influential interviews of the year on this week’s episode.

Featured Guests

Annie Duke

Author, National Poker Champion

Annie Duke is a World Series of Poker bracelet winner, the winner of the 2004 Tournament of Champions and the only woman to win the NBC National Poker Heads Up Championship. She has authored four books on poker and in 2018 released her first book for general audiences called "Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don't Have All the Facts," which is a national bestseller.

Bill Browder

CEO Hermitage Capital, Head of Global Magnitsky Justice campaign, and Author of Red Notice

Bill Browder is the founder and CEO of Hermitage Capital Management, which was the investment adviser to the largest foreign investment fund in Russia until 2005, when Bill was denied entry to the country and declared a "threat to national security" as a result of his battle against corporate corruption.

Following his expulsion, the Russian authorities raided his offices, seized Hermitage Fund's investment companies and used them to steal $230 million of taxes that the companies had previously paid. When Browder's lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, investigated the crime, he was arrested by the same officers he implicated, tortured for 358 days, and killed in custody at the age of 37 in November 2009.

Since then, Browder has spent the last 5 years fighting for justice for Mr. Magnitsky. The Russian government exonerated and even promoted some of the officials involved so Browder took the case to America, where his campaigning led to the US Congress adopting the 'Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act' in 2012, which imposed visa sanctions and asset freezes on those involved in the detention, ill-treatment and death of Sergei Magnitsky (as well as in other human rights abuses). This law was the first time the US sanctioned Russia in 35 years and became the model for all subsequent US sanctions against Russia. Browder is currently working to have similar legislation passed in Magnitsky's name across the European Union.

Jack Schwager

Best-Selling Author and Expert in Futures and Hedge Funds

Mr. Schwager is a recognized industry expert in futures and hedge funds and the author of a number of widely acclaimed financial books. Mr. Schwager is one of the founders of Fund Seeder (FundSeeder.com), a platform designed to find undiscovered trading talent worldwide and connect unknown successful traders with sources of investment capital. Previously, Mr. Schwager was a partner in the Fortune Group (2001-2010), a London-based hedge fund advisory firm. His prior experience also includes 22 years as Director of Futures research for some of Wall Street's leading firms, most recently Prudential Securities.

Mr. Schwager has written extensively on the futures industry and great traders in all financial markets. He is perhaps best known for his best-selling series of interviews with the greatest hedge fund managers of the last three decades: Market Wizards (1989, 2012), The New Market Wizards (1992), Stock Market Wizards (2001), Hedge Fund Market Wizards (2012), and The Little Book of Market Wizards (2014). His other books include Market Sense and Nonsense (2012), a compendium of investment misconceptions, and the three-volume series, Schwager on Futures, consisting of Fundamental Analysis (1995), Technical Analysis (1996), and Managed Trading (1996). He is also the author of Getting Started in Technical Analysis (1999), part of John Wiley's popular Getting Started series.

In 2015, Mr. Schwager partnered with TradeShark to release a set of proprietary indicators including Trend Weight, Overbought/Oversold, Directional Weight, and Dual Trend, accompanied by a series of eight videos explaining these indicators.

Mr. Schwager is a frequent seminar speaker and has lectured on a range of analytical topics including the characteristics of great traders, investment fallacies, hedge fund portfolios, managed accounts, technical analysis, and trading system evaluation. He holds a BA in Economics from Brooklyn College (1970) and an MA in Economics from Brown University (1971).

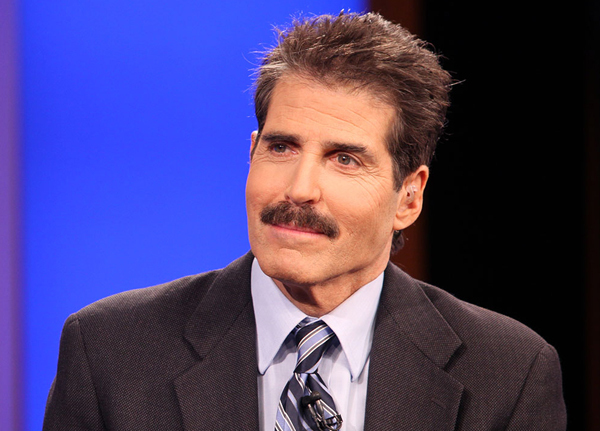

John Stossel

American television personality

John Stossel, American television reporter and commentator, best known for his role on the ABC newsmagazine 20/20.

Stossel graduated from Princeton University in 1969 with a B.A. in psychology. He soon began a career in television journalism, working initially as a researcher for KGW in Portland, Oregon, and then as a consumer reporter for WCBS in New York City. He worked as a consumer editor for ABC's Good Morning America before becoming a correspondent for 20/20 in 1981. In time, Stossel's role on the program expanded, and his occasional segment "Give Me a Break," in which he skeptically examined topics ranging from education to government regulation, eventually became a regular feature of the show. In 1994 "Give Me a Break" was transformed into a series of one-hour prime-time specials that enjoyed consistently strong ratings. In 2003 ABC named Stossel a coanchor of 20/20.

In 2009 Stossel joined the Fox News Channel and Fox Business Network as a special series host, author of the blog John Stossel's Take, and anchor of the weekly news program Stossel (2009-16), focusing on libertarian issues.

Stossel's reporting garnered numerous awards, including Emmy Awards and a George Foster Peabody Award. In addition to his activities in broadcast journalism, he promoted Stossel in the Classroom, a video designed to help teachers develop their students' critical thinking skills. Stossel also wrote Give Me a Break (2004), Myths, Lies, and Downright Stupidity (2006), and No, They Can't: Why Government Fails--But Individuals Succeed (2012).

Raoul Pal

CEO and Co-Founder of Real Vision

Raoul Pal is a former hedge fund manager who retired at 36, Raoul Pal is a co-founder of Real Vision, a financial media company offering in-depth video interviews and research publications from the world's best investors. He has run a successful global macro hedge fund, co-managed Goldman Sachs' hedge fund sales business in Equities and Equity Derivatives in Europe, and helped design the BBC TV program Million Dollar Traders, training participants in investment and risk management strategy. Raoul retired from managing client money and now lives in the Cayman Islands, from where he manages Real Vision and writes for The Global Macro Investor, a highly regarded original research service for hedge funds, family offices, sovereign wealth funds, and other elite investors.

Episode Extras

2:38 – Dan looks back at the conversation with professional poker player, Annie Duke (episode 181), on how to better analyze your past decisions… “Colloquially when we say mistake, what we mean is we got an outcome we didn’t like, as opposed to the decision making was poor.”

11:12 – Dan revisits a conversation he had with legendary macro investor Raoul Pal (episode 140) from earlier this February… “I think the dollar and gold go together, and eventually gold is the last man standing…”

20:50 – Dan brings back a clip with author Matt Ridley (episode 154), who spoke during the height of the market crash this year… “It turns out, you can’t direct innovation, you can’t plan it, you can’t design what we’re going to invent next, you have to let people experiment and come up with solutions, and if you do that, they will come up with solutions, including solutions to pandemics…”

28:09 – Bill Browder (episode 153) shares his wild story about being detained in Russia… “It eventually became the largest investment fund in the country with $4.5 billion under management… And in the process of doing my investments, I discovered that every single company I was investing in… was being robbed blind by the management and the oligarchs who controlled the companies…”

37:30 – Jack Schwager (episode 183) shares some lessons he’s learned from interviewing the biggest names in investing over the past 3 decades… “People try to look to the news as to why the market went up or down and they’ve got it COMPLETELY backwards…”

44:55 – Mark Minervini (episode 141) outlines some steps new traders can take to develop a system and hone their craft… “The main key is you have confidence in it… If you don’t have confidence in the underlying strategy, it’s not going to work. It could be the best strategy in the world, but a strategy takes an operator, and it takes discipline to follow it.”

53:42 – Gad Saad (episode 175) tells listeners that you must be ferocious when defending your beliefs, “Don’t be an unnecessary martyr, but don’t also subcontract your voice to others… if everybody were to speak out against these idea pathogens, we will win the battle of ideas very quickly.”

1:02:45 – Bethany McClean (episode 148) shares some incredible insights into the Enron scandal… “To me the line between a great visionary and a great fraudster is much finer than you might think, and I don’t know that we get the great visionaries if you don’t also have the space for the great frauds to happen…”

1:10:30 – John Stossel (episode 159) and Dan discuss how regulation often starts with good intentions but ends up doing more harm than good… “As they continue to add more [regulations], they probably do cost lives… Because they make us poorer and wealthier is healthier. And also because they make us less self-aware…”

Transcript

Announcer: Broadcasting from the Investor Hour studios and all around the world, you're listening to the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music plays]

Tune in each Thursday on iTunes, Google Play, and everywhere you find podcasts for the latest episodes of the Stansberry Investor Hour. Sign up for the free show archive at investorhour.com. Here's your host, Dan Ferris.

Dan Ferris: Hello and welcome to a special episode of the Stansberry Investor Hour. I'm your host, Dan Ferris. I'm also the editor of Extreme Value. Before we get into today's episode, don't forget Trish Regan is now part of the Stansberry family. Check out her podcast, American Consequences With Trish Regan. The link will be in the description of this episode.

Today on the show, we're taking a look back at our favorite interviews from past episodes and seeing how our guest predictions panned out and what their advice did over the year. From absolute legends of investing to professional poker players and professors discussing free thinking, this year's interviews have easily been some of the best we've ever done. And it's been a crazy year for financial markets, for the U.S. economy. And if you recall in a recent episode, one of our listeners wrote in the mailbag and quoted Vladimir Lenin, who is attributed this quote where he said, "There are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks where decades happen." I'd say that's a pretty darn good quote for 2020. A ton of stuff happened in a very short time this year. That and more right now on the Stansberry Investor Hour.

[Music ends]

So, last episode I looked back at my 10 surprises from 2020, from our first episode of 2020, and I talked about how they turned out. And that's what we're going to do a little bit again today. And you may recall... during my conversation with professional poker player Annie Duke from a few weeks ago, we talked about this. We talked about analyzing your past decisions so you can learn from them. It's some of the best analytical advice I've ever heard and it's so simple, anybody can do it. Take a listen. Here's Annie Duke from Episode 181 on November 19.

[Clip plays]

Dan Ferris: There's two hard parts: how do we assess the outcome, and then how do we know we made a good or bad decision if the immediate outcome, on one or two occasions, is not of primary importance? This is a big deal I think.

Annie Duke: It is a big deal. So let me think about it as a retrospective problem and then – meaning, you made a decision, you already got an outcome – how do you figure it out? And then I think it'll roll back into your – as you're making new decisions, what you need to be doing. So if we think about the retrospective problem, obviously outcomes in the aggregate, if we have enough data, are quite informative. So if I can flip a coin 1,000 times I can tell you lots and lots about the coin. For example, whether it's fair. But the problem in terms of the way that our mind works is that we don't really wait for decisions in the aggregate to work out. Like we don't wait to have a huge data set before we make any decisions, and we tend to be processing those outcomes in sequence – in other words, one at a time. And that's where we can really get into really big difficulties.

And there're certain types of investing that you can do, as you know, where it's hard to wait for a lot of data in the aggregate because you may not actually be investing in too many things and they may have very long feedback loops. So this sort of becomes a problem if we're going to – and the other thing that becomes a problem because of the resulting thing is that, colloquially, when we say mistake what we mean is we got an outcome we didn't like.

Dan Ferris: Yeah.

Annie Duke: As opposed to the decision was poor. So if you invest in a stock and it goes down, you'll tend to say you made a mistake. Which of course is – it shouldn't even really be a sentence of English because I have no idea if you made a mistake just because it went down. There's a whole bunch of other things that I would need to know. So essentially the way to address it is to basically try to do two things. One is reconstruct your state of knowledge at the time of the decision. And then the other is reconstruct what a decision tree would've generally looked like.

So let's take the first one. I've got this tool in the book which is called a knowledge tracker. So basically what you would say is, "What did I know at the time of the decision?" So there're certain things that you can't know. One of the things that becomes really obvious when you think about, "What did I know at the time of the decision?" is that you did not know the way it would turn out. So just right there that's actually really helpful, to say: "Let me write down what're the things that I knew at the time of the decision." Because what is not contained in there. that the stock went up or down, for example.

So now at least you can get some separation from that. But it's going to be inputs. It's going to be – it could be "what are the unit economics?" Or "what are the earnings projections?" What do I think" – and then you can sort of look at: "What is the data? What are the things that I knew that went into the decision that were facts? And then what was I thinking? What were my beliefs about those facts?" So it could be that the company is predicting they're going to make 100 widgets over the next year, but I actually think that that's an underestimate, and I think they're going to be able to produce 120 widgets over the next year, and I think I know something different than what the market does.

So you're basically just thinking about "what were the inputs into the decision?" Then you look at "what are the facts that reveal themselves afterwards?" So there'll be certain facts. Like you'll know how many widgets it actually produced, as an example, right? You'll know something about whether it went up or down. You may know – there may be an acquisition that occurred, or whatever it might be, right? So you say, "Here are the things that I knew before the fact. Here are the things that I knew after the fact. And now let me look at the things that I knew after the fact and ask myself, "Were any of these things actually knowable to me beforehand?"

For most of the stuff that reveals itself after the fact, the answer to that is going to be no. For the things that you say yes, you would say, "OK, it was knowable to me beforehand but could I afford it?" In other words: "Did I have enough time to go find it out? Was it reasonable for me to understand that this was actually an important thing for me to know at the time?" Because a lot of times the answer to that is going to be no, that that revealed itself to you later. It could be that it cost too much money to get the information. There could be a variety of things. But let's say that you say, "Yes, I could've known about it before the fact and I didn't go find it out," then it's not about beating yourself up... it's saying, "OK, let me make sure that I wrap that into any future decision that I might make."

If something revealed itself that was knowable that you didn't realize that you needed to know but now you do, you would wrap that into your decision making going forward. And then for the whole set of things that weren't knowable beforehand, generally they're not going to be knowable for the next decision that you make so you would recognize that and you would just say, "I'm not going to worry too much about that category."

So basically what this allows you to do is, through this kind of knowledge tracking, is to say, "What I really care about when I'm assessing a decision is what was my state of knowledge at the time that I made the decision? Because that's going to actually help me figure out whether the decision was good or not. Because I can start to see... were there gaps in my knowledge where I actually should've known that?" And then you can do a second thing and you can say, "So, given what I knew at the time," you can sort of reconstruct a tree and you can say, "What did I think the chances of different outcomes were?" And then you can look and say, "Was I a pretty good predictor of what that set was?"

Now, the thing that I'll say about this is that you can go and reconstruct all of that if you want to. But obviously the better thing to do is to do that work before you make the investment in the first place and actually record: "What are the facts that're going into my decision? What are the assumptions that I'm making about it? How am I modeling the data that I'm looking at? What does that mean for what I predict the probability of different outcomes occurring is?" And if I believe that I know something more than the market does here, let me actually be very specific and not leave that as implicit. And say, "I'm going to explicitly state, 'Why do I think that the market has this underpriced or overpriced?'"

Because that's why you would invest – you either think it's underpriced or overpriced. Otherwise you'd be indexing, right? So I'm assuming you're not indexing. "And let me actually explicitly state what I think the market has wrong." And now that allows you to actually get a better lookback because you can now compare your expectations to how the world actually unfolded.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: Well, that is wonderful advice. And I love the way she turned it on us at the end. She said, "Go back and be very honest about your state of mind before you made this decision, at the time – right up to the time you made the decision, be very honest about what you knew back then." And that's hard enough. Most people really – we human beings, we like to justify and rationalize and tell ourselves stories about what happened after the decision. But it's a great exercise to go back and reconstruct your state of mind at the time of the decision. And then at the end she says, "Why not just do all this work before you invest, before you make the decision?"

Wow. That's wonderful advice. I hope you took notes while she was talking because those are two great points. Go back and look at the decisions you made, but, hey, why not just do this work ahead of time? Great stuff. All right. So that's sort of the reason – well, not sort of. That's exactly an explanation of why I did the look back at my 10 surprises for 2020. Same thing. Because the state of my mind at the time of the decision is recorded for posterity in the first episode of 2020. So I don't get to lie about that. So it gives us a really nice snapshot of the thinking at the time. And then we can assess how it turned out.

All right. Over the course of this year, of course, lots of guests made some really interesting predictions. Back in February I spoke with macro investor Raoul Pal, CEO and co-founder of Real Vision. And Raoul famously pontificated for us, as only he can do, about the power of the U.S. dollar versus gold. And, man, that episode, it's like finding a time capsule. Take a listen to Raoul Pal, Episode 140, February 6.

[Clip plays]

Raoul Pal: So the very macro level, I use the business cycle to understand where we are. Now, with the ISM in the U.S. – is my indicator, one of my indicators of the business cycle – it was just below 50... it's just above 50. So it tells you – and it peaked a long time ago. So it tells us we're in the down phase of the great cycle. So we're expecting at some point a recession.

Dan Ferris: And just for our listeners, what is the ISM, Raoul?

Raoul Pal: The Institute for Supply Management survey. It basically surveys a bunch of buyers within the largest companies in American and asks them about financial conditions, market conditions, their inventories, their expectations for the future. And it blends it all together and gives you an indicator that it's been going essentially in one way, shape, or form. There was the Treasury survey before that. Since about 1910 or something, 1917. So there's a huge amount of data. And what's interesting I found about it is: All the asset prices are correlated. Basically the year-on-year change in the S&P, bond yields, copper, emerging markets, everything is related to the business cycle.

The one thing that's the least related to the business cycle, bizarrely enough, is the U.S. dollar. The U.S. dollar being the reserve currency of the world, has a number of different drivers. It's called a Bayesian distribution, which means that many things influence it, unlike let's say bonds, which are really influenced by inflation and interest rates. So there's a lot of inputs into a currency market. But the real big one here for people, listeners here to concern themselves over, is that in this bizarre world of massive monetary quantitative easing, there's not enough dollars in the world to service the debts. It's like a game of musical chairs.

The issue is... the foreigners – so the off-shore-dollar borrowing market – is about $15 trillion. And it's truly enormous. And in the U.S., obviously when we see the corporate debt markets and all this, it's absolutely gigantic. But that whole amount of dollar borrowings and a slowdown in economic growth has meant it's the musical chairs to borrow the dollars, which is why periodically you're seeing things like the Argentine currency or the Turkish lira or South African rand blowing up... there's not enough dollars out there.

Now, as the dollar goes higher, it drives down the price of commodities, because all commodities are priced in dollars. And that creates yet more of a shortfall. It also means that there's kind of less lubrication for the financial system globally. So the dollar is pretty much everything right now. And in the dollar – the Fed trade-rated dollar index, it's pretty much got its nose pressed against the ceiling of all-time high. So it's extremely strong. And that's causing problems across the world.

Dan Ferris: Does it surprise you to see a strong dollar and strong gold prices at the same time?

Raoul Pal: No. My core thesis for some time was we were going to see both together, which is a very rare occurrence. Normally gold falls as the dollar rallies because it's denominated in dollars. But gold started outperforming 27 of the world's currencies. I have a GMI currency basket which doesn't include U.S. dollars. And gold started to outperform those, which was telling us that monetary easing, or that quantitative easing, was actually devaluing all currencies against gold.

Now, the dollar and gold – because the dollar shortage, and gold being the rare asset – are both rallying together in this phase. Eventually the dollar too will top out. I think it's going to come much higher than here. Maybe even 20% higher than here. Something quite devastating. And that will cause a massive devaluation of the dollar as other countries have to abandon it. And we're hearing the talk of digital currencies and the move away from the dollar. So I think the dollar and gold go together, and eventually gold is the last man standing. I think there's other things too, whether it's cryptocurrencies or whatever. But that's generally my overall macro view for the longer term.

Dan Ferris: I've actually noticed, Raoul, with you, ever the past, I don't know, I want to say year or so, you've been tracking the massive bubble in equity valuation as it rises. But you're really shy about – you don't want to short it though. That's just not the way to go at it for you. Why is that? Why don't you want to do this?

Raoul Pal: So I've learned this from my 30 years of experience in this. So if you think of the reaction function of markets and the macro sensitivity of asset classes, the most macro-sensitive of all is the short end of the bond market. Because that is when they cut interest rates. It basically reflects that. There's very little froth bubble – you get bits of overexposure and underexposure. But generally it reacts as it's supposed to to cuts in interest rates. The next one is the long bond, which has some future expectations built in. So it's not quite as pure. Then I would say it's the commodity markets, which have quite a lot of speculation in. But they tend to reflect macro fundamentals. Then probably currencies, and then finally equities, because it's basically human emotion built on kind of long-term earnings expectations.

So I found that the reaction function of the Federal Reserve say that if growth slows they will cut rates. Therefore, own bonds. So that's an easy trade. People tend to get confused and want to do the vanity trade, as I call it, which is short equities. Now short equities, they come with much higher volatility. They don't look like a call option, which is what let's say the short end of the bond market looks like, which means that you get – they're unlikely to raise rates, but there is a high probability they cut rates. So therefore it looks like a call. It's a one-sided risk reward. Equities aren't. And you can see that in Tesla today. It's a really problematic market, particularly at the peak of bubbles and the peak of the cycle. So even though it's a clear bubble – it is impossible not to even think of it as a bubble now – you shouldn't do anything about it. If you do, just own bonds. It's a much better bet, and there's a much higher risk/reward in all circumstances.

So a great example – again, to talk about true learnings, a friend of mine who's a great trader was running his own macro hedge fund back in 2000. He was extremely bearish and short as much as possible, and he lost 30% and had to close his fund. Why was that? The volatility of the equity market short was too high. In fact, over that 2000 bust, the equity market went up more days than it went down. So you ended up getting stopped out every time that you should've been adding to the trade. It was a really difficult situation, and it really taught me to be careful what instrument you use to express your view.

And my old boss at GLG who founded and ran GLG, his view is very simple. He said, "Just keep it to the most simple expression of the view." Paul Tudor Jones was always the same. He said, "Don't give me complicated trades. Give me the simplest, purest expression and stick to that. Because then you can apply leverage to it if you want to. But you understand what bet you're taking."

Dan Ferris: So purest, simples though – if I could just follow this line of thinking – and it makes perfect sense – how is buying bonds purer and simpler than shorting equities if you're bearish on equities? Just walk me through that.

Raoul Paul: Because you know that if the equity market falls, the Fed are going to cut rates. So if you – you're actually trading – you're trading an economic view, which is the economy is slow and therefore equity's at the wrong valuation versus where the economy is. OK? That's essentially what a bubble is. So if you're trading the economic view, then the most macroeconomic sense is the bond market. So trade the bond market. Because the Fed will cut if rates – if the equity market cracks. We saw it in 2000, we saw it in 2008. So you know the Fed have got your back in the trade. The Fed don't have your back in the equity market trade because usually you get a few of these massive rallies every time the Fed cut. So in which case, you'll make money in the bond market but you'll lost money in the equity market.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: OK. So that's Raoul Pal talking, February of this year, before everything took place. Before interest rates went down to zero. And so the bond trade was a brilliant call at that moment. And we talked about other things with him, and we talked especially about the coronavirus and the impacts on the economy, and he pretty much nailed that too. The only thing I will say is that Raoul has been a bit surprised by the dollar weakness that has characterized the movement after the big spike up in March. So he sort of got it right initially but then it's been a bit of a surprise, really kind of to all of us, that the dollar's been so weak. But overall I think Raoul did a really great job. And he's obviously a very sophisticated guy. Lots of good advice there. Don't do the vanity trade. Don't short equities. Buy bonds if you're bearish. I think that's a great idea.

And, speaking of coronavirus, which – how can you not talk about coronavirus in the year 2020? Here's another clip with one of my favorite guests. I'm so happy that we were able to talk with him. This is award-winning author Matt Ridley speaking when the whole corona-thing was pretty new still on May 14, Episode 154. Here's Matt Ridley.

[Clip plays]

Dan Ferris: You know, an interesting question here that's come up between myself and some folks on Twitter – there's a bit of a debate about how free do you want to be versus how bad do you want to stop this virus? Is it OK to sort of shut everything down and have the government shut everything down, and does that really make things better? Are we really doing ourselves a favor by doing that? Where do you come down on this issue, Matt? I know you've written quite a bit about the role of government. What does it look like to you?

Matt Ridley: Yeah. My instincts are liberal, libertarian. I want people to be free to do what they want. I think the only way we've achieved what we have as a civilization is by giving people the freedom to come up with things. It's very much the theme of my next book, How Innovation Works. The subtitle is And Why it Flourishes in Freedom. Because it turns out you can't direct innovation. You can't plan it. You can't design what we're going to invent next. You have to let people experiment and come up with solutions. And if you do that they will come up with some good solutions, including solutions to pandemics.

But at the same time, I have to admit that, given we don't have a vaccine, given we don't have a cure for this disease, it is what they call non-pharmaceutical interventions, in other words quarantines and curfews, that is going to defeat this, as it did for many centuries in the case of other pandemics. And it's only less than a century ago that quarantines were routine for people with typhoid, people with whooping cough, et cetera, that you were supposed to close your door and stay at home. And bad luck if you couldn't earn any money and you didn't have enough food and things like that. At least we hopefully will not have that problem on the same scale. But it is very very hard for people.

The problem, you and I know, is that when this is over, will the restrictions, will the authoritarianism, will the central edicts go away? Or will they stay? I mean, Britain introduced food rationing during the Second World War and didn't lift it, didn't remove food rationing until 1954, something like six years after Germany had done so. Why? Because the food rationing bureaucrats said, "Oh, we need food rationing." What they meant was "I need my job rationing food." And there was a lot of that problem continued.

The one thing I think we need to also look at is whether or not we were doing enough medical innovation before this. If we'd been seriously apprised of the risk of a pandemic, we should perhaps have allowed vaccine development and other medical issues to be more free to experiment, more free to look into things. There is a tremendous amount of red tape that has been swept away in the last three or four weeks, in the USA but also in the United Kingdom, about developing drugs, about developing tests, about developing vaccines. And you have to ask yourself if we didn't need those rules now, then why did we need them before?

Dan Ferris: Yes. And you and I both know, Matt, that many people will read the situation exactly opposite, won't they? They'll say, "Why wasn't the government putting people on this and why weren't we spending more government money, more tax dollars trying to find solutions and vaccines and whatever it would've taken to have on hand before such a thing happened?"

Matt Ridley: It is true that you can make a case for market failure in this area. In other words, that big pharmaceutical companies do not spend as much money on vaccines as they do on drugs because vaccines are wickedly difficult things to develop with relatively low success rates, and when they do get developed, they usually come in just too late, just when the epidemic's gone away.

So, for example, the Ebola vaccine was developed during the 2014 outbreak. But by the time it came in, Ebola had largely gone away. It's come back again more recently. But it's very difficult to make money out of vaccines for emerging diseases like this. So in that sense, it does make sense for people like the Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust to put money into a coalition for epidemic preparedness innovation. Not public money but charitable money. Which they did in 2017. And it's probably a good thing in this pandemic that we have such a thing. But it would've been nice if they'd done it 10 years earlier.

Oh, one more point on that if I may. I don't know about you, but I'm someone who thinks that we are overreacting to climate change. We're spending too much money on a problem that is relatively less important than some others. And that's a very unfashionable view. It's very difficult to express it without being accused of crimes against humanity and things like that. But I feel this crisis has vindicated that view, in the sense that so much of our effort has gone into saying that climate change is by far the greatest problem that humanity faces in this century, and we've just had a sharp reminder that it's not, that there are much more urgent threats to humanity and that they've been under-resourced in recent years.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: What a reasonable, thoughtful guy. Matt says that, "Hey, I'm a libertarian-leaning guy," and yet he entertains all kinds of viewpoints. Like most libertarians, for them, market failure is like a four-letter word, but he entertains a lot of scenarios and a lot of ideas. And his books are great too. Any time you find a Matt Ridley book, you got a good read in front of you.

Now, speaking of political freedoms, which we talked quite a bit about with Matt, man, who can forget when Bill Browder was on the show? That was a great interview. Bill Browder – he's the author and the CEO of Hermitage Capital Management. He shared his story about losing most of his personal freedoms in Russia, where he stumbled upon a huge scandal that helped put Vladimir Putin in power. Lover him or hate him, like him or not, Bill has fascinating stories. Give a listen. Here's Bill Browder, Episode 153, May 7.

[Clip plays]

Bill Browder: I come from a family of American communists. My grandfather, Earl Browder, was the head of the Communist Party of the United States of America from 1932 to 1945. He ran for president against Roosevelt as a communist in 1936 and 1940. He was imprisoned in 1941, pardoned in '42, expelled from the Community Party in '45, and then ultimately persecuted very viciously during the McCarthy era of the 1950s. So when I was going through my teenage rebellion I was trying to figure out the best way of rebelling from this family of communists, and I came up with this great idea, which was to put on a suit and tie and become a capitalist. And I became a capitalist at the age of 17.

And I eventually found my way to Stanford Business School in 1987, graduating in 1989, which was the year that the Berlin Wall came down. And as I was trying to figure out what to do post-business school, I had this epiphany, which is that if my grandfather was the biggest communist in America, I'm going to try to become the biggest capitalist in Eastern Europe. And that led me to London and it ultimately lead me to Salomon Brothers, which doesn't exist anymore but is a famous – was a very famous Wall Street firm, probably the most famous Wall Street firm, immortalized in a book called Liar's Poker, which I recommend everyone read if you haven't read it already.

And that's when I became a financier. That's when I became a financier focused on Eastern Europe. And that led me to all the other dramas of my life.

I left Salomon Brothers. I moved to Moscow in 1996 and I set up an investment fund called the Hermitage Fund. I started with almost no assets under management. But it eventually became the largest investment fund in the country, with $4.5 billion under management. And in the process of doing my investments, I discovered that every single company that I was investing in – and these were all publicly traded mostly oil and gas companies, a few metals companies, a few other bits and pieces, all publicly traded. I discovered that all of these companies were basically being robbed blind by the managements and the oligarchs who controlled the companies.

And so let's say I owned 1% of a company – I didn't really have 1% of anything because the oligarch who owned 51% of the company was literally siphoning 100% of the profits out the back door for his own benefit. And so I decided to try to challenge that corruption, to fight the corruption. And I didn't have a lot of tools at my disposal. It wasn't like you could go to the Russian SEC and say, "Look at these terrible things... You need to prosecute somebody." Because Russian SEC was neither prosecuting anybody, or even had the ability to. And I couldn't go to the police. I couldn't go to the parliament. I couldn't go to anywhere.

But the one interesting lever that I had was that I was good at doing research. I had a good team of investment analysts and I knew a lot of journalists in Moscow. And so we would research how they went about stealing the money. And it wasn't as opaque as you might think. Russia's an incredibly bureaucratic country, and all the bureaucracy gathers information and keeps it somewhere, and we just needed to figure out where they kept it. And eventually we found out where they kept the information. So we were able to figure out who was doing the stealing, how they were doing the stealing, when they were doing the stealing, and where it was going to. And then we'd take that information and I'd share it with the journalists that I had met and knew. And of course the journalists loved me because I saved them three months of their own work by doing this analysis for them. And they would publish these stories.

And it turned out that when we started publishing these stories and exposing the oligarchs, we were doing it at a really weird and opportune moment, which was – the moment that Vladimir Putin had come to power, he was fighting with the same guys that we were fighting with. The oligarchs were stealing power from him at the same time as they were stealing money from us. And I should point out, I've never met Vladimir Putin. I've never spoken to him in my life, neither then nor now or any time in between. But this was one of these situations where your enemy's enemy is your friend. So Vladimir Putin was busy fighting with the oligarchs because they were stealing power from him. I was fighting with the oligarchs because they were stealing money from me. And so every time I would come up with one of these scandals, he would step in in some kind of very heavy-handed way and stop them from doing what they were doing.

And so for a period of time, I had the most golden life you could ever imagine because I was cleaning up Russia, I was making money for my clients and myself hand over fist, and I was doing it in a much more powerful way than anyone could've ever envisaged because why would some guy from the South Side of Chicago have all this ability to get Putin to do stuff? Well, it just turned out to be this weird confluence of interests.

But the problem was that Putin wasn't doing this because he wanted to make Russia a better place. Putin was doing this because he wanted to defeat the oligarchs. And so he decided to go for broke at the end of 2003. In October of 2003, the richest man in Russia, a man named Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who owned the oil company Yukos, he was on his private jet, just landed in Siberia on his way to some business meetings for his oil company. His jet was surrounded by a bunch of secret policemen from Russia's FSB, which is the successor organization to the KGB. They arrested him. They brought him back to Moscow. They put him on trial. And they allowed the television cameras to come into the courtroom and film the richest guy in Russia on trial sitting in a cage.

And this had a profound impact on the other oligarchs of Russia, who thought to themselves, "Wait a second, I don't want to go sitting in that cage." And so they went to Putin in the summer of 2004, after Khodorkovsky was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison, and they said to him, "Vladimir, what do we have to do so we don't have to sit in a cage?" And Putin said, real simply, "Fifty percent." Not 50% for the Russian government, not 50% for the presidential administration of Russia, but 50% for Vladimir Putin.

And at that moment Putin became the richest man in the world. And at that moment all of my interests were no longer in confluence with his but were directly in opposition. And as I continued to expose corruption, instead of going after his enemies, I was going after his own personal financial interest. And that was the leadup to November 5, 2005. As I was flying back to Russia, I was stopped at the border. I was detained in the airport detention center, arrested, and put in the airport detention center, kept there for 15 hours, and then deported the next day, 15 hours later, and declared a threat to national security.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: I mean, that story is like – it's one step shy of a James Bond plot or something [laughs]. It's crazy. Man. And you should listen to that whole episode, Episode 153. Because it actually gets even crazier than that. Wow. What an incredible story.

[Music plays]

My colleague and friend Dave Lashmet is on fire right now. His average-close pick this year alone has returned 187%, almost triple your money. Today he's got a time-sensitive $13 stock pick that he believes is set to explode. This is an opportunity you don't want to miss. Listen to Dave's take, along with all of his evidence on the stock, over at investorhourtech.com. Check it out.

[Music plays]

We talked to a lot of great investors this year. And what a year to talk to them. All kinds of different people... long-term value types and short-term traders. And I'll tell you, when it comes to short-term trading, there's one name that – I bet you already know this name. And I hope you listened to this episode. If you didn't, as soon as you've fished with today's episode, go listen to this. If you're a trader, you have to hear it. And that guy's name of course is Jack Schwager, the author of the famous Market Wizard series of books. Any trader who hasn't read ever word of every Market Wizards book is missing something and needs to do it. And Schwager was with us recently, Episode 183, December 3. And he talked about the rises and dips in the markets and how the charts that traders use aren't really the indicator that they used to be. Here's Jack Schwager, Episode 183, December 3.

Dan Ferris: Every day the market went up 0.5% because of this, and it went down 0.5% because of that, and it's all noise.

Jack Schwager: Yeah. It's more than that. You know, this is one of the great ironies. It's one of the things I point out in that book Market Sense and Nonsense... people kind of try to look to the news for why the market went up and down. They got it completely backwards. You know, the market goes up or down, and unless there's really some development of consequence, which is usually not the case, then people have to come up with some reason of why the market went up and down. And they fit some reason. And that reason could've been there, you know, all along, and the market went up that day and it went down other days. And that reason is still there. But they'll pull it out and say, "Well, the market went up because people started to pay attention to this." Or whatever.

So it doesn't tell you why the market went up and down. Actually, most of the gyrations in the market are based – well, the major trend is based off underlying, driving fundamentals. Whereas the daily gyrations just – that's not related to news most of the time. It's usually just, you know, the market fluctuating around its basic trend and reacting to being short-term oversold or overbought. Things like that. It's not – the news you read, typical financial papers on why the market is up or down, is usually not the reason.

And in fact, I even have a quote in the book, I have an example where it was a Federal Reserve annual meeting, and the chairman sort of made some comments in the morning, and the markets were down. And the news was: "Well, the markets are disappointed Bernanke's comments. You know, it's still up because" – the same day the market went up, it closed higher. And I swear, the same news service: "The market was up today because encouraged by Bernanke's comments." The same comments. Nothing happened. The comments were made before the opening. When the market opened lower, it was why the market was down. And when the market closed higher, it was why the market was up. I mean, this happens all the time.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. It's funny. A couple weeks ago on the podcast, I covered two headlines that occurred within 24 hours of each other, totally opposite explanations for the same – or they were the identical explanation for opposite moves [laughs]. It's just ridiculous. And you can tell – it's a big tell, isn't it? It's like they never tell you why the market's going to do what it's going to do tomorrow. It's always they're back-fitting the story to what happened yesterday. Why don't they ever tell me what's going to happen tomorrow?

Jack Schwager: That's their job. Their job is to do that. By the way, in this new book – this is kind of an interesting, useful point I think for listeners. And one of the traders I interviewed, fellow by the name of Jason Shapiro, he's a real contrarian trader but one of the most useful things he said in that interview was – his favorite word is despite. Despite. "If you ever see, 'The market went up today despite this news,'" he said, "That's a really bullish signal." Because when they can't even explain why the market's up, they have to explain it went up despite opposite news, that in itself is telling you something. So it's kind of a related point, I think, is worthwhile knowing.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. I thought you made a similar point I want to say in the section – your little narrative section right after the Peter Brandt interview. There was a section I thought where you had said – I could have this wrong. I could be confusing it with another part of the book.

Jack Schwager: Yeah, it's OK.

Dan Ferris: But it was like you were saying basically... when people say, "Well, it was the old Fed quantitative easing is going to crash the market" story, and people were – that was a huge despite, right? Despite, despite, despite for years and years and years. And the thing just keeps going up and up and up.

Jack Schwager: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. Peter's an interesting guy, isn't he? Peter Brandt. He's your first interview in the new book, Unknown Market Wizards.

Jack Schwager: He trades on charts. But his real points are – that's not the charts. Charts don't predict anything. He's just giving useful points where to put on trades. But what really drives his results in terms of return to risk is his absolute risk management. And he has lots of comments and suggestions and advice about risk management, lots of different rules. You know, some that you kind of don't hear everywhere. Like he has one rule he calls his Friday rule, which is: if he has any position on as of the Friday close which is losing money – doesn't make a difference how much – if he's not ahead in the position by Friday's close, he'll get out. And he says that rule saved him a lot of money over the years. Just one example. But he has lots of those types of rules.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. That's an interesting interview because he comes right out and says, "Long-term chart patterns don't work anymore." I mean, he says it in plain, clear English.

Jack Schwager: Yeah.

Dan Ferris: That kind of didn't surprise me, but it's still – it blew me away a little bit.

Jack Schwager: Well, this is from a man who has traded on charts all his life and profitably. But his thing is, the charts don't – you know, he emphasizes over and over, "The charts don't predict anything." But what they are useful for is – there are points at which, based on the pattern, there's a realistic shot that the market is going to go significantly, one way or the other. And it's a higher-probability point in time.

It doesn't mean that that prediction – let's say it looks like the market is formed like say hedge holders or whatever that's completed, and it looks like it's ready to go. And he thinks the market's going to go higher. It doesn't mean that that's a reliable prediction this market's going up. It means that there's some reasonable probability that this might be a point where the market takes off. And if it, you know – he'll put a position on. Moreover, it has to be a point where he can define – it has to be a type of pattern where he can define a close point, a close stop point, which tells him he should be out.

And so those are the points he looks for where there's a reasonable possibility it might be the beginning of a new swing and he can take the trade and not risk too much. And if he's wrong, he's out.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: So, yeah, we always wind up, when we talk to traders, talking about what? Risk management. That's where they all wind up. And we didn't just talk to Jack Schwager this year, the Market Wizards guy. We actually spoke to one of the market wizards who was interviewed in his book Stock Market Wizards. I'm talking about Mark Minervini of Minervini Private Access. Mark was with us earlier in the year. He outlined the steps that new traders can take in order to begin to hone their craft and develop their own system. Here's Mark Minervini from Episode 141 on February the 13.

Mark Minervini: In the beginning, no matter what we do, we mimic. If you were to start off as a basketball player or a football player, you're going to probably watch your favorite sports star and you're going to mimic them and you're going to learn from a coach and you're going to learn through trial and error. So you're not going to develop a trading methodology and be making lots of money in the stock market in any kind of short period of time.

So really it's matching your personality to the method. And then once you get that method down, maybe you're able to do the type of things that I suggest and you're getting some traction, and you can start maybe adding in your experience, and maybe then you – that's what I've done. I mimicked the best and then, over the years, a lot of years, I started developing some of my own techniques. And it just becomes a passing of the torch. It's not like everything I do is unique. But there's a lot of things that are unique over a number of years.

But the main thing is you have to match your personality. If you're someone who doesn't want to sit in front of the screen all day and doesn't want to do a lot of work and a lot of trading and making a lot of fast decisions, well, then day trading is probably not for you. But then again, you might have a different personality. So you really have to match the style and find something that makes sense to you. Because the main key is that you have confidence in it. If you don't have confidence in the underlying strategy, it's not going to work. It could be the best strategy in the world, but a strategy takes an operator, and takes discipline to follow it. So that's really the linchpin to following any strategy.

I mimicked traders and successful people. Didn't just try to emulate their style or vaguely emulate them – I really looked at what they believed and how they thought and exactly how they operated on a daily basis, and really dug deep into the mindset behind the person. Because again, if you don't think like that person or if you don't have that mindset then you're not going to follow the strategy because it might go against your beliefs or your idiosyncrasies or your own emotions and foibles.

So you really have to have some congruency. Best way is, if you think like someone, you can perform like them. But if – you could even learn the techniques of someone but if you don't – maybe they think very positive and they believe they can win, and you learn the exact same techniques and you get taught from the best in the world – Michael Jordan teaches you how to play basketball, but you don't believe you can be a good basketball player, or you don't believe in the process and the techniques. It doesn't matter how good of a coach you have... You're not going to be good at it because the beliefs are really what's important.

Dan Ferris: There was something in the Market Wizards interview that kind of surprised me a little. You said, "The essential principle is that the stop loss point should be a function of the expected gain." And that surprised me because I think in the same interview you said something about the good traders manage the downside, they don’t worry about the upside. Your mention of the expected gain is what surprised me because, like all the wizards, your focus seems to be constantly on the discipline and cutting losses, and just that mention of the stop loss point being related to the expected gain surprised me. Can you help me out there?

Mark Minervini: So, what is your stop? How do you define your stop? How do you decide at what level that you stop out? Well, I can tell you this... if your average gain – if your expected gain or your strategy delivers an average gain of let's just say 8% on average per trade, well then you obviously can't take 10% losses. You'll be losing money. And depending on how often you're correct – I mean if your strategy was right 90% of the time, yes, you can take losses that are larger than your gain. But that's generally not the case. Usually most traders, over time, their batting average or the percentage of profitable trades is somewhere around 50/50. They're wrong just as often as they're right.

So I like to have a minimum of two-to-one. So if I'm cutting my loss at 5% then I need to justify that with an average gain of 10% or greater, preferably even three-to-one. So that's what that's about as far as determining. Some people say, "Well, I'm going to cut my loss. I read a book and it said to cut your loss at 8%." But their average gain is five, and they're right 45% of the time, and they're losing money. "I'm cutting my losses." What's going on here? You have to work on getting a larger average gain to justify that amount of risk or you've got to back into a tighter risk parameter and you're going to have to have a tighter stop loss.

Dan Ferris: In your books, you give so many very specific things like the amount of stop loss and the amount of loss of your portfolio that you should tolerate on a given trade and stuff. Are these primarily examples, or is this valid criteria like – the criteria that are all throughout Think and Trade Like a Champion, are they more examples or what?

Mark Minervini: Well, first of all, about 90% of all the examples that are in all my books and in the 450-page workbook that we give to the attendees of the workshop that I conduct, 90% of them are my actual trades that I did. So this isn't like hindsight or looking back and saying, "Oh, this would've worked." These are actual trades that I did... 90% of them, not all of them. There are some that were great examples that I missed or we went back further than I was trading. But 90% of them.

The other thing is that I am doing nothing different than I've been doing for the last three decades. Today I do exactly what I've been doing. Very little has changed. I've just refined it a little bit more and I'm not as aggressive. I don't have to be. I don't have to trade for a living so I'm just not as aggressive. At one time I had my whole account in one or two names and a lot of risk. So that's the only difference... I'm just not as aggressive, and I've improved my techniques even better than ever. But I'm doing the same thing. Nothing has changed. So I definitely did not move on to something else. I don't see why I would when what I do has been working and it keeps working, So there's no reason why I would move on to something else.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: Very cool. The guy has been doing the same thing for decades. He's just sort of refined it and less aggressive. That sounds really interesting to me, especially since we heard Jack Schwager say that Peter Brandt was telling us that the long-term chart patterns don't work anymore. Obviously Mark is not relying on those patterns. What a cool interview. And what a nice guy. Really cool guy. And he said something basically that I've said many times this year: investing needs to be personal. You need to match your personality to the way that you trade and invest in financial markets. It's a great lesson. And I'm afraid that too many people don't learn it. They think they can just kind of pull a strategy off the shelf and do it in a very mechanical way.

But the point that you heard Mark made is true... if you don't come up with it yourself, if it's not your strategy, if you don't make it your own, you're not going to have the conviction to ride out the underperformance that inevitable. Every strategy has periods of underperformance. And if you don't make it personal enough and dig deep and really find yourself in the strategy, you don't succeed. Really great lesson. It's one of the great all-time lessons of investing.

So you can be bull-headed or bear-headed [laughs]. You can be any kind of a personality. But you have to know what the best method is for you. Or you can be like a honey badger, as my Dr. Gad Saad says. I loved our interview with Gad Saad. I love his book, which I highly recommend. It's called The Parasitic Mind. We talked about it on our interview. And Gad said, "You should be like a honey badger. Be ferocious and adamant in your believes." So here's from our interview with Gad Saad, Episode 175, October 8.

Gad Saad: I would argue that the types of nonsense that the right and left espouse, the attacks on truth, are not equivalent in how poisonous they are. Let me explain why. The right might reject a particular theory, whereas – that we know is true, a scientific theory. Say, you know, "We reject evolution because," whatever, "our Christian beliefs." But, on the other hand, the left has completely rejected the possibility that truth even exists.

So, one of the idea pathogens that I discuss in the book, the granddaddy of all idea pathogens, is postmodernism. Postmodernism is the, quote, "Philosophical movement" that argues that there are no objective truths, right? Everything is shackled by subjectivity. Everything is shackled by our personal biases. There is no such thing as a truth.

Well, as you might imagine, that's very disconcerting to a scientist because we do wake up every morning thinking that there are truths to be uncovered. We do use the scientific method thinking that we're going to make some contribution to some greater truth. Now, of course, truth can change, right? What was truth in science 300 years ago may need updating. That's why we talk about provisional truths in science. But the epistemological attack on truth – the fact that the left or some leftists negate even the possibility that truth exists – that strikes me as profoundly more nefarious as an idea pathogen than anything coming from the right. Do you follow what I'm saying?

Dan Ferris: Yeah. When you discuss epistemology in that way, it reminds me of things that Ayn Rand used to write about that same topic.

Dr. Gad Saad: Right. And let me just add to the point about the epistemology of truth. The scientific method is the only game in town. The scientific method is exactly what frees us from the shackles of our personal identities. There is no Lebanese-Jewish way of knowing. There is no indigenous way of knowing. There is no fat-person way of knowing. There is no transgender way of knowing. All of those identities are left at the door when you enter the arena of the scientific method. That's what makes the epistemology of the scientific method so great and so liberating.

So when you have someone, for example, in Quebec – so the Quebec minister – I discussed this in The Parasitic Mind. I think it was the Quebec minister of the environment or something. They were having a conversation about, you know, doing environmental studies before you do something. And he said, "Well, what do you mean? Isn't the scientific method the only way by which we're going to adjudicate these decisions?" And he was considered a vile – I mean, you couldn't tell that he wasn't Hitler because he was arguing that we shouldn't be going to indigenous way of knowing. There's only the scientific method.

Now, let me explain. If the indigenous people have been living in a particular land for 10,000 years, then of course they have fauna-specific and flora-specific knowledge because they have lived in that land. So we can go to the indigenous folks and say, "Since you have lived in this ecosystem, please teach us about the fauna and flora of the land." But the process by which we uncover truths within that ecosystem is the scientific method. There is no booga-booga. There is no ancestral praying to the ancient gods as an alternative to the scientific method. So once you start allowing for multiple ways of knowing, you're an intellectual terrorist, and all this nonsense is coming from leftist imbecilic professors. If only I was a bit more direct in my language. I feel like I'm too shy, no?

Dan Ferris: [Laughs]. You are. You are. But what do you really mean, Gad? Come on.

Dr. Gad Saad: I know. I need to find a way to come out of my shell and be a bit less cryptic. I'm working on it. I'm working.

Dan Ferris: [Laughs]. OK. It's a process, right.

Dr. Gad Saad: It's a process. Exactly.

Dan Ferris: Let's just take me – or anybody, but we'll pick on me. I'm not a professor of evolutionary science. What on earth do I know? Who's going to listen to me talk about reason and truth?

Dr. Gad Saad: Right. I got you. That's a concern that I often receive from people, right? They write to me, "Hey, professor, I really want to get engaged. But, you know," like you said, "I'm not some fancy professor. I don't have a large audience." And I tell them, "Look, it's trench warfare, right? It's house-to-house. It's trench-to-trench. Some of us have big platforms. Great. We use that. But you don't have to have a big platform to contribute to the battle of ideas. Your professor says something that is insane, challenge them politely. Someone says something on Facebook that you disagree with, engage them politely. You hear something happening at the pub that you think you might weigh in on? Don't refrain from doing so."

And usually there's a couple of reasons why people refrain from doing so. "Well, if I weigh in, I might lose their friendship." Well, guess what? If their friendship is not sufficiently anti-fragile – to use my friend's Nassim Taleb's point, if our friendship is not sufficiently anti-fragile that it could withstand the stressors of us disagreeing about some important point, then you know what? Don't let the door hit your ass on the way out. I don't need friends like that.

I prefer to have two really good friends that I can have deep, meaningful conversations with than a bunch of, you know, cowardly, castrated morons who are going to be completely triggered because I say something that is contrary to them, right?

So in other words, any of the concerns that people propose to justify why they don't speak is ultimately – and I'm sorry to say – a measure of their cowardice. Look, I grew up in Lebanon, where at any second I didn't know if I was going to be executed, blown away, shot by a sniper, stopped at a roadblock and executed. That was my childhood reality until we escaped. So boo-hoo-hoo about you're going to lose a friend or your boss might be upset at you. We all have a cross to bear. And the question is, look, don't be an unnecessary martyr, but don't also subcontract your voice to others. Don't say, "Don’t worry. Gad Saad has this on my behalf." If everybody were to speak out against these idea pathogens, we will win the battle of ideas very quickly. If everybody stays silent – you know, cowed in their apathy – then we will lose this battle. It's really as simple as that.

That's why I tell people: activate your inner honey badger. The reason why I use the honey badger in my call to action is because, for any of your viewers who are unaware of this, a honey badger the size of a small dog is so ferocious that if six adult lions come after it, they retreat. How could that be possible? How could six lions retreat from a small-looking dog? Well, because it is extraordinarily fierce. And so what I tell people is, "Be a honey badger when it comes to defending your principles."

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: Be a honey badger when it comes to defending your principles. We live in such a weird time. I think it's a great message. I love Gad Saad. I love his message and I was inspired to write a piece for the Stansberry daily Digest about freedom of speech, about how important speech is, and how it must – you must be free to speak. Even if what you have to say is, in the modern parlance, hate speech, you must be free to say it. And you're not free enough to say it throughout academia and other places in our modern world. I think Gad Saad is a man of our time. He's for our time. He is in the right place in the right time. And I'm grateful that he's there.

All right. So we spoke with Bethany McLean as well this year. You may remember Bethany as one of the co-authors of The Smartest Guys in the Room, the book about the Enron scandal, the scandal known as Enron. The whole company was one giant scam, right? And I found Bethany very thoughtful. We spoke to her in April when COVID was still a relatively new phenomenon. We talked about that. And we talked about – we were philosophical. We talked about why don't human beings ever learn? And she talked about the line between a visionary and a fraudster, which I thought was a profound insight. So give a listen. This is Bethany McLean, Episode 148, on April 2.

[Clip begins]

So, one thing I noticed that I want to say about The Smartest Guys in the Room, which is the definitive account – it's an awesome book – everybody ought to read it. It doesn't take you long, does it, to get to a scandal? It's like in the first chapter or two you get to the first early scandal. In the early history of the company there's the trading scandal with – what was it? – Enron Oil, I think it was called?

Bethany McLean: Yeah. The whole Enron story is still to me fascinating in so many ways, not just the canaries in the coal mine along Enron's trajectory, how Enron itself was a canary in the coal mine for all sorts of problems we've seen later on, which I think is why the scandal has such legs... because it was indicative of so many things.

Dan Ferris: It's a story for our time. As I was reading this thing, I thought, well, even though I know that this happened 20 years ago or something, it feels like it could be happening right now. It just feels very current to me somehow still. It's like every 10 years when the market collapses you can just read The Smartest Guys in the Room, and, yeah, it's about like that every time.

And it seems to me though like you've kind of focused on those kind of stories. Like the other really big book you wrote was All the Devils Are Here: The Hidden History of the Financial Crisis. And then you wrote that other smaller book called Shaky Ground about Fannie and Freddie, another aspect of the mortgage crisis there. And, again, it's like we never learn. I feel like human beings, we just never learn. What is it about us human beings? Have you learned anything – in all these hundreds of pages that you've written and researched, is there some insight you can share with us about humanity that helps us understand how Enron just seems to happen every ten years?

Bethany McLean: Well, I think there are lots and lots and lots of reasons, right? I think it is indicative of just very human failings. And so, to some extent, I think it's a story that's just destined to play out over and over again. I don't necessarily think it's even a bad thing, in that to me the line between a great visionary and a great fraudster is much finer than you might think. And I don't know that we get the great visionaries if you don't also have the space for the great frauds to happen. And I think we want the space for the world to move. And so I think sometimes these great frauds are just the inevitable cost of having enough space for there to be a visionary too, for there to be one person that really can transform and move the world.

That said, I do worry that our current times are both corrupt on a macro level and on a micro level. And corrupt is a strong word. But I guess what I mean by that is that obviously free money makes disasters more likely to happen. So _____ _____ the financial crisis of super-cheap money, I think we're going to see the collapse of a lot of things that probably shouldn't've gotten to the size that they were. So there's a macro environment that I think has probably corrupted the normal course of business a little bit.

And then on a less grand kind of monetary policy but more micro level, I also worry that some of the things we see happening now are indicative of just late-stage capitalism, that some of the responsibility of a business being located in a city where people knew everybody has just gotten lost in this globalization of a business, and that people don't feel as much responsibility as they used to, and that we've somehow devised a system where the people at the top can walk away with great fortunes from businesses that otherwise collapse.

Maybe that's not unique to modern times. Maybe thus it ever was so. But that feels problematic to me, when those at the top manage to take all the rewards and bear none of the risk, right? Nothing wrong with people at the top taking the lion's share of the reward as long as they also bear the lion's share of the risk. And I worry just something has gone wrong in that equation. I mean, you look at the financial crisis and most of the people at big banks and the heads of big banks did pretty well. I mean, sure, they lost a lot of money. But people walked away with tens of millions of dollars and it did this devastating damage to the American population, some of whom haven't recovered from it when we're already onto the next crisis. That strikes me as something just fundamentally wrong.

Dan Ferris: Yeah. So you have me thinking, Bethany, of two things. First of all, when you were talking about visionaries who are – the line between sort of fraud and great visionaries is closer than you think, I immediately thought of Steve Jobs and his reality distortion field. And I thought, wow, if anybody had a reality distortion field – actually, I think Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling and Fastow even – they all had their own version of the reality distortion field at Enron. So there were multiple overlapping fields. And the other thing is that it seems like it's the first really big story in which a managerial class, not an operator owner class, took over a business and kind of ran it into the ground for self-serving purposes and just out of sheer ego and hubris. And I think that's a huge thing that's happened.

We had a guy named Ben Hunt on the program who's been all over that story. And I think you actually have – just in writing your book and in covering Enron and some of the other things that you've written about over the years, whether you meant to or not, you covered that [laughs].

Bethany McLean: Yeah. That's interesting. Although I don't know that entrepreneurs are exempt from their own flaws. I hear you on the managerial class, and it is a really interesting phenomenon. Enron is a little bit different in that it was almost a startup within an old-school oil and gas company. And the startup that Jeff Skilling created – it combined with the old-school business too, and the fatal flaws in both kind of took down the whole operation. So Enron's sort of a weird mixture of the two. I wouldn't put it in as simple a category as a managerial story.

[Clip ends]

Dan Ferris: Really good interview. The thing that jumped out at me was when Bethany was talking about the current moment where the corruption is from a macro level, and easy money makes for these fraud stories like Enron became. And so it follows, doesn't it, that the easiest money would be the biggest, most corrupt, most disastrous fraud. And I agree. That's where we are. When there's $18 trillion of negative-yielding debt in the world, I'm going to call that the easiest money [laughs], right? When interest rates are zero and the Fed keeps upping the amount that they buy each month in the bond market, I'm going to call that the easiest money. And I hope we're wrong about that. But I think Bethany had a great insight there, and I'm afraid that it really is true.

All right. One more of these to go. And what better one to finish off with than John Stossel. John was on in Episode 159 back in June. And we talked John's book really. We talked about how too much regulation can have bad unintended consequences and pretty much always does. And he even outlined how some examples of seemingly helpful changes that we make in society just make things worse. So here's John Stossel, Episode 159, June 18.

[Clip begins]

I was looking through your book, No, They Can't, and you did a neat little device in here that explains a lot of this problem, I think. And every couple of pages you've got a new section and it starts with a little box, and in the little box it says, "What intuition tempts us to believe versus what reality taught you." And an example here is "seat belt laws save lives" – that's what intuition tempts us to believe. What reality taught me? Seat belt laws also cost some lives, and nobody ever talks about that. And, you know, that's a fairly controversial opinion, and all those little boxes in the book have fairly controversial opinions [laughing].

John Stossel: I left my Fox TV show because I wanted to reach young people, and my son said, "Dad, you know, people aren't going to believe – aren't going to trust what you say about markets when you're on Fox. And you don't need a network anymore. You've got a million Twitter followers, and with social media now you can reach people." And they do – young people do watch short videos. So, we're at least making people aware that there's another way to think about these things, that the answer isn't always another government program.

You brought up seat belts earlier. Now, that's an example of making things less safe, somewhat less safe, by trying to make them more safe. In that, once you require seat belts – first of all, seat belts would've happened anyway. They were already coming before they were made mandatory. But when people wear seat belts, we drive faster. One, there's something called the Peltzman Effect, after the University of Chicago economist who proposed it. He said the best safety device, instead of a seat belt, would be to have a spike aimed at the driver, mounted on the steering wheel, because that would make you drive much more carefully. And we are more reckless with seat belts.

On the other hand, seat belts clearly do save lives, because cars are really dangerous, and the seat belts do make a difference there. So that's one nanny state intrusion that almost certainly has saved lives. But as they continue to add more, they probably do cost lives. One, because they make us poorer, and wealthier is healthier, and also because they make us just less self-aware. We trust that, "Oh, everything must be safe because there must be regulation for this," so we don't check.